The Yellow Sea Dispute: Provisional Arrangements and Persistent Deadlock

- January 22, 2026 |

- Issue Brief

Summary

The Yellow Sea maritime boundary remains unresolved 25 years after provisional arrangements, as China and South Korea cannot reconcile legal positions on delimitation. China’s infrastructure installations since 2018 have employed grey-zone tactics, while economic interdependence constrains Seoul’s response.

Introduction

The Yellow Sea maritime boundary dispute exemplifies how provisional solutions can calcify into a persistent deadlock. For a quarter-century, the 2001 Fisheries Agreement between South Korea and China has governed this strategically vital waterway through temporary arrangements intended to bridge irreconcilable legal positions while both sides negotiated a permanent boundary. Yet in January 2026, when South Korean President Lee Jae Myung raised urgent concerns with Chinese President Xi Jinping about massive steel structures China has installed in disputed waters since 2018, the fundamental boundary question remained as unresolved as ever.[i] The summit produced limited agreement—China would relocate one structure and resume long-suspended delimitation talks—but left untouched the core legal disagreement that has prevented resolution for over a decade.[ii] What was designed as an interim framework has become the only governing arrangement for one of Asia’s most contested maritime spaces.

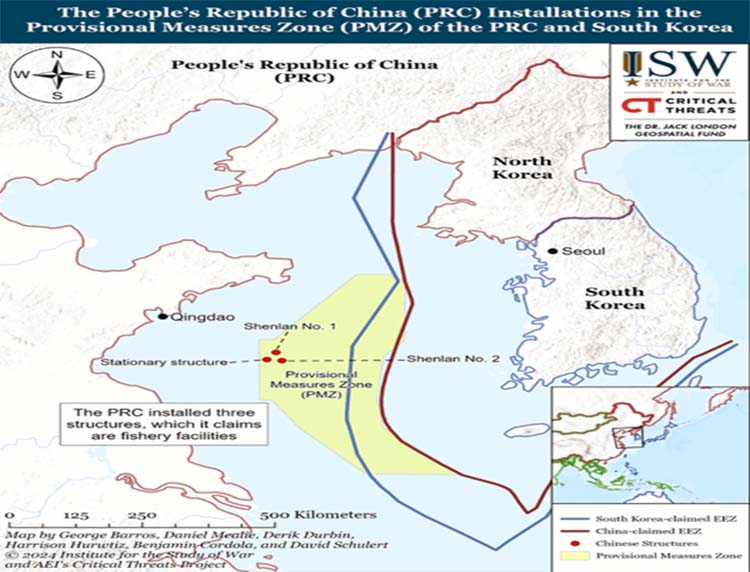

The conflict centres on overlapping claims to exclusive economic zones (EEZs) in waters too narrow for both countries to exercise their full rights under international law. The Yellow Sea measures less than 400 nautical miles at its widest point, yet the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) allows coastal states to claim EEZs extending 200 nautical miles from their shores.[iii] This geographic reality necessitates boundary delimitation, but China and South Korea have failed to reach an agreement despite over a decade of negotiations. South Korea advocates a median line dividing the sea equally. At the same time, China insists on an ‘equitable principle’ that considers coastal length, population and geographic features. This approach would give China a larger share of the disputed waters.[iv]

Beyond legal questions, the dispute affects critical strategic and economic interests: the Yellow Sea provides maritime access to both Beijing and Seoul, hosts critical military installations including China’s Northern Fleet headquarters and the United States’ most extensive overseas military base at Camp Humphreys, and contains fishing grounds worth billions of dollars annually.[v] Decades of violent fishing conflicts, including fatal incidents in 2008 and 2010, underscore the human costs of unresolved claims. China’s recent infrastructure installations have intensified concerns, with South Korean officials privately expressing worry about “creeping sovereignty” reminiscent of China’s expansion in the South China Sea.[vi]

This issue brief examines why the Yellow Sea maritime boundary remains unresolved after a quarter century of provisional arrangements and assesses whether the January 2026 summit represents genuine progress or tactical accommodation. It explores how temporary measures have calcified into persistent deadlock, analysing the legal, strategic and economic dimensions that prevent resolution. The brief examines South Korea’s strategic dilemma between economic dependence on China and security concerns, and uses grey-zone warfare as an explanatory framework for understanding Chinese behaviour since 2018. The brief evaluates diplomatic efforts, including the recent Xi-Lee summit and explores why previous resolution attempts failed. While often overshadowed by tensions in the South and East China Seas, this dispute carries significant implications for regional stability, alliance credibility and the rules-based maritime order.

Historical Background and Legal Framework

Fishing conflicts between China and South Korea date back to the mid-1950s and occurred sporadically through the early 1990s, long before either country claimed exclusive economic zones.[viii] These early tensions reflected competition over rich fishing grounds in a relatively shallow sea—averaging just 44 meters in depth—that has sustained coastal populations for centuries.[ix] However, the modern legal dispute began with the ratification of the UNCLOS. China ratified UNCLOS in 1996 and claimed a 200-nautical-mile EEZ in 1998; South Korea followed similar steps in 1996.[x] The overlapping claims were immediately apparent: the Yellow Sea’s maximum width of less than 400 nautical miles made it impossible for both countries to claim their full EEZ entitlements without conflicting in the centre.

Recognising the need for interim arrangements, China and South Korea entered into negotiations that lasted approximately seven years. They tentatively agreed to a fisheries framework in November 1998, officially signed the Agreement on Fisheries between the Republic of Korea and the People’s Republic of China in August 2000, and it entered into force on 30 June 2001.[xi] This was the first provisional arrangement to regulate overlapping EEZ claims between the two countries.

The agreement established several key elements: exclusive fishing zones for each country, a jointly managed Provisional Measures Zone (PMZ) in the area of overlapping claims, transitional zones with limited shared fishing, a Joint Fisheries Commission for coordination, and a flag-state enforcement system.[xii] Critically, the agreement included a ‘without prejudice’ clause stating that its provisions would not affect final maritime boundary delimitation.[xiii] The 2001 agreement also explicitly prohibited permanent installations within the PMZ, though it remained silent on aquaculture and other non-fishing maritime activities—an ambiguity that would later prove significant.[xiv]

Despite the provisional framework, efforts to establish a permanent maritime boundary have repeatedly failed. Vice-ministerial talks on boundary delimitation began in 2015 but quickly ran into an irreconcilable disagreement over the fundamental principles for drawing the line.[xv] South Korea advocates the median line or equidistance principle, which would roughly divide the overlapping area equally between the two countries—a standard approach under UNCLOS for opposite coasts.[xvi] China, however, insists on an ‘equitable principle’ that takes into account coastal length, population and geographic features such as the natural prolongation of land territory.[xvii]

This approach, which China has employed in other maritime disputes, would award Beijing a significantly larger share of the disputed waters. After making little progress, the talks were suspended in 2017 following what officials described as limited advancement.[xviii] The seven-year hiatus that followed—until the January 2026 agreement to resume negotiations—underscores the depth of the legal impasse. Over a decade of talks has failed to bridge the gap between these incompatible legal positions, leaving the 2001 provisional framework as the only governing arrangement a quarter-century after its intended temporary implementation.

Strategic and Economic Significance

The Yellow Sea’s strategic importance extends far beyond its role as a fishing ground, serving as a critical gateway for both Chinese and South Korean national security and economic interests. Geographically, the sea provides maritime access to Beijing via the port of Tianjin, located just 67 miles inland from the coast, and to Seoul through the Han River and Incheon port.[xix] In China, the Yellow Sea hosts the headquarters of the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s Northern Fleet in Qingdao. It provides access to major submarine construction facilities at Huludao and Dalian in the adjacent Bohai Sea, which China has claimed as an ‘inland sea’ since 1958.[xx]

South Korea’s second-largest deep-water port, located in Incheon, sits on the Yellow Sea coast, making control of these waters essential for the country’s maritime commerce and coastal defence.[xxi] The United States maintains its largest overseas military installation, Camp Humphreys, just 15 kilometres from the shore of the Yellow Sea, underscoring the area’s significance for American force projection in Northeast Asia.[xxii] The sea’s strategic value is not merely contemporary; it has been contested throughout history, hosting major naval battles during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), and serving as the site of the pivotal Incheon amphibious landing in 1950 that changed the course of the Korean War.[xxiii]

Economically, the Yellow Sea’s fishing grounds have sustained coastal populations for centuries, though overfishing has severely depleted stocks in recent decades.[xxiv] The Korea Fisheries Association estimates that illegal Chinese fishing alone costs South Korean fishermen approximately US$ 1.1 billion annually in lost catches and damaged marine ecosystems.[xxv] Beyond fisheries, the Yellow Sea is believed to contain significant oil and gas reserves, though these remain largely unquantified and unexploited due to the unresolved boundary dispute.[xxvi] The sea also serves as a critical shipping corridor for both countries’ trade, with thousands of commercial vessels transiting its waters annually. These overlapping strategic and economic interests—combined with the geographic impossibility of both countries exercising full EEZ rights—create inherent tensions that the 2001 provisional framework was designed to manage but has increasingly struggled to contain.

The Current Crisis: Chinese Structures in Disputed Waters

The simmering maritime boundary dispute entered a new, more acute phase in 2018, when China began deploying permanent infrastructure in the Provisional Measures Zone. In July 2018, China launched Shenlan 1, the first of what it described as large-scale aquaculture cages designed to breed salmon in deep waters.[xxvii] The structure, a massive steel cage extending dozens of meters below the surface and measuring approximately 100 meters in length and 80 meters in width, represented a significant departure from traditional fishing activities.[xxviii]

Simultaneously, China began deploying observation buoys throughout the PMZ—at least 13 have been identified since 2018, officially designated for meteorological research and marine science.[xxix] In 2024, China escalated further by launching Shenlan 2, an even larger aquaculture cage, and installing a converted oil rig, dubbed the Atlantic Amsterdam, to serve as a management platform complete with a helipad, housing facilities and an operations centre.[xxx] A dedicated support vessel, the Luqingxin Yuyang 60001, has been operating continuously in the area since 2017, tending to these installations and making frequent trips between the structures and ports in Shandong province.[xxxi]

While China maintains that these installations serve purely commercial aquaculture purposes within its ‘coastal waters’, South Korean officials and independent analysts have raised significant concerns about their dual-use potential and strategic implications.[xxxii] Former South Korean Coast Guard chief Kim Suk-kyoon has noted that the sensor-laden meteorological buoys could be reconfigured to detect and monitor submarine movements and naval vessels—a particularly sensitive issue given the Yellow Sea’s relatively shallow depth and its role as a transit route for Chinese submarines from Bohai Sea facilities.[xxxiii] The scale and permanence of the structures also contradict the 2001 Fisheries Agreement’s explicit prohibition on permanent installations within the PMZ.[xxxiv] China argues that aquaculture activities were not explicitly addressed in the agreement and therefore fall outside its restrictions, exploiting what South Korean officials view as a critical legal ambiguity.[xxxv] In December 2024, South Korea’s parliament passed a resolution characterising the structures as a ‘violation of maritime rights’, though this symbolic action did not change Chinese behaviour.[xxxvi]

The crisis intensified in 2025 as China expanded beyond infrastructure to more overt demonstrations of military capability and enforcement authority. Chinese naval forces conducted exercises in the PMZ using the country’s largest aircraft carrier. In contrast, Chinese maritime authorities unilaterally declared temporary no-sail zones in waters that both countries are supposed to manage jointly.[xxxviii] Most troubling for Seoul has been the systematic harassment of South Korean government vessels attempting to monitor the Chinese installations. Since 2020, the Chinese Coast Guard has intercepted South Korean research vessels on 27 out of 135 monitoring attempts, including a particularly tense 15-hour standoff in the spring of 2025 involving the South Korean research vessel Onnuri.[xxxix] While observers note that these confrontations have not become physical in the manner seen in the South China Sea—where Chinese vessels have rammed and water-cannoned Philippine and Vietnamese ships—the pattern of interference represents a clear assertion of de facto Chinese control over areas designated for joint management.[xl]

This constellation of activities has led analysts to characterise China’s approach as ‘grey zone’ warfare—the use of ambiguous, incremental actions that fall below the threshold of armed conflict but cumulatively alter strategic realities on the ground.[xli] Victor Cha of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies observed that the Yellow Sea situation “started the same way” as China’s South China Sea expansion, where initial claims of purely civilian purpose eventually gave way to militarised artificial islands.[xlii] The grey zone framework helps explain several elements of Chinese behaviour: the use of plausibly deniable ‘civilian’ infrastructure rather than overt military installations; the gradual escalation that avoids triggering a crisis response; the exploitation of legal ambiguities in the 2001 agreement; and the reliance on coast guard vessels rather than naval forces to maintain a veneer of law enforcement rather than military confrontation.[xliii] Analysts debate whether this represents tactical patience before a more aggressive phase or a genuinely different approach than the South China Sea—a question the January 2026 summit sought to address.

South Korea’s Strategic Dilemma

A key strategic dilemma limits South Korea’s response to Chinese encroachment in the Yellow Sea: China is both Seoul’s most vital economic partner and its biggest maritime security threat. In 2025, bilateral trade reached approximately US$ 331 billion, with China accounting for US$ 168 billion in South Korean exports—around 25 per cent of the total—and US$ 139 billion in imports —representing 23 per cent of the overall imports.[xliv]

South Korean conglomerates like Samsung and LG have heavily invested in Chinese manufacturing and supply chains, creating mutual dependencies that complicate confrontational policies. The 2016–2017 THAAD crisis strongly influences Seoul’s decisions. When South Korea agreed to host the United States’ Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) missile system, China responded with severe economic retaliation, including tourism boycotts, restrictions on Korean entertainment content, and informal barriers to Korean businesses operating in China.[xlv] The financial damage was significant and showed Beijing’s willingness to use commercial relationships as strategic weapons. This precedent limits South Korean policy options: each protest over Yellow Sea structures or boundary violations must be carefully considered against the risk of provoking THAAD-style retaliation, which could lead to billions in lost trade and investment.

The security dimension adds further complexity to Seoul’s position. While the US–ROK Mutual Defence Treaty provides strong deterrence against conventional military attack—particularly from North Korea—its applicability to grey-zone provocations remains ambiguous. Chinese ‘aquaculture facilities’ and coast guard harassment do not clearly trigger alliance commitments designed for armed aggression.[xlvi] South Korean officials privately worry about a deterrence gap: the alliance effectively prevents war but may not prevent the incremental loss of maritime space through sub-threshold coercion.

Moreover, South Korea requires Chinese cooperation on the most immediate threat to its security—North Korea. Beijing’s substantial influence over Pyongyang makes Chinese goodwill essential for managing DPRK provocations, pursuing denuclearisation, and maintaining stability on the peninsula.[xlvii] This creates a two-front problem in which both the Yellow Sea dispute and North Korean management involve China, giving Beijing leverage over multiple pressure points simultaneously.

Domestic political pressures further complicate Seoul’s options. President Lee Jae Myung’s progressive government faces growing anti-China sentiment among the South Korean public, frustrated by illegal fishing, maritime encroachments and perceived Chinese assertiveness.[xlviii] The parliament’s resolution condemning Chinese structures reflects this public mood, yet Lee must balance nationalist pressure with pragmatic recognition of economic realities. With elections scheduled for June 2026, the president needs to demonstrate strength without triggering a crisis that could damage the economy or destabilise regional security. Lee must simultaneously satisfy domestic demands for firmness while avoiding confrontation that Beijing might escalate—leaving Seoul with limited room for manoeuvre and helping explain why the January 2026 summit’s modest achievements may represent the maximum politically sustainable outcome.

The January 2026 Summit and Diplomatic Efforts

The January 2026 summit between Presidents Xi Jinping and Lee Jae Myung represented the highest-level diplomatic engagement on Yellow Sea issues in years. It took place at a symbolically significant moment—Lee’s first visit to China since the pandemic and his first major foreign trip as president. That Lee chose Beijing over Tokyo for his inaugural state visit underscored the centrality of the China relationship, despite mounting tensions.[xlix] Lee arrived with a delegation of South Korean business leaders, including executives from Samsung, SK Group and LG, signalling the economic dimension of the diplomatic outreach.[l] The maritime agenda focused on two interrelated but separate tracks: the immediate issue of Chinese structures in the PMZ and the longer-term challenge of boundary delimitation.

On the structures issue, China agreed to relocate one installation, though neither government publicly specified which structure, the relocation timeline, or verification mechanisms to ensure compliance.[li] South Korean officials characterised this as progress, with one foreign ministry representative noting there appeared to be “room for some progress through the working-level meetings held so far”.[lii] Beyond the structure commitment, both sides issued a joint statement pledging to make the Yellow Sea “a peaceful and co-prosperous sea” and to continue “constructive consultations” through existing working-level channels.[liii] The two countries also signed 14 memoranda of understanding covering trade, technology and environmental cooperation, demonstrating the breadth of the relationship beyond maritime disputes.[liv]

On the more fundamental boundary question, Xi and Lee agreed to resume vice-ministerial talks on maritime delimitation “within this year”—marking the end of a seven-year hiatus since negotiations were suspended in 2017.[lv] This resumption represents a necessary but far from sufficient condition for resolution. The fundamental disagreement between South Korea’s median-line approach and China’s equitable principle remains unresolved, and over a decade of previous negotiations has failed to bridge this gap.[lvi] The decision to maintain separate dialogue tracks for the structure issue and boundary delimitation may facilitate progress on discrete problems. Still, it could also prevent the comprehensive settlement that many analysts believe is ultimately necessary.

The summit’s achievements must be measured against its limitations. Only one structure of many was addressed, with no commitment regarding the other installations, observation buoys, or the management platform. No transparency mechanisms or inspection protocols were agreed upon, leaving South Korea unable to verify that structures serve only commercial purposes. The agreement contains no enforcement provisions, and China’s track record in the South China Sea—where initial civilian claims eventually revealed military purposes—justifies caution.[lvii] Whether the summit represents a genuine turning point in managing the dispute or simply the minimum concession necessary to reduce immediate diplomatic pressure while preserving China’s strategic gains will become clearer as implementation unfolds through 2026.

Why Resolution Remains Elusive

Despite a quarter-century of provisional arrangements and multiple diplomatic initiatives, a permanent resolution of the Yellow Sea maritime boundary remains elusive for both legal and strategic reasons. At the most fundamental level, South Korea’s median line approach and China’s equitable principle are not merely different preferences but irreconcilable legal methodologies, each with legitimate grounding in international maritime law.[lviii] The median line, which would roughly divide overlapping waters equally, represents the standard UNCLOS approach for opposite coasts and is supported by international case law. China’s equitable principle, which would weight the division by coastal length, population and geographic features, also has precedent in certain boundary disputes but would award Beijing a substantially larger share of the disputed waters.[lix] Any compromise requires one side to accept significantly less than its claimed legal entitlement—a politically difficult concession involving national sovereignty and prestige. Over a decade of formal negotiations from 2015 to 2017 failed to identify a middle ground between these positions, suggesting the gap may be unbridgeable through bilateral diplomacy alone.

Beyond legal disagreement, the two countries face asymmetric incentives regarding time and resolution. For China, delay serves strategic interests: the longer the provisional status quo persists, the more its physical presence in the PMZ normalises and becomes difficult to challenge.[lx] Each year of Chinese structures operating without resolution makes their removal more politically and economically costly. South Korea, conversely, needs a timely resolution to clarify maritime rights, halt encroachment, and prevent further erosion of its position. This asymmetry in urgency gives Beijing little incentive to compromise. The economic leverage imbalance compounds this problem: South Korea’s greater dependence on trade with China than China’s on trade with South Korea means Seoul has more to lose from a confrontational approach that might torpedo negotiations.[lxi] Geographic proximity also favours a sustained Chinese presence—maintaining coast guard patrols and infrastructure support is easier for China than for South Korea to monitor and challenge continuously.

Available resolution mechanisms have proven inadequate to overcome these obstacles. Bilateral negotiations have stalled on the fundamental legal question. International arbitration under UNCLOS remains theoretically possible, but China might reject such proceedings as it did after losing the 2016 South China Sea arbitration, and even a favourable ruling for South Korea could take years to adjudicate, with uncertain enforcement.[lxii] No neutral arbiter commands sufficient trust from both sides to mediate effectively. Meanwhile, the Joint Fisheries Commission addresses only fishing quotas and conservation, not sovereignty or boundary questions.[lxiii] Military or coercive options risk escalation that neither side wants and could trigger a broader regional crisis. This absence of effective mechanisms for breaking the deadlock, combined with the legal impasse and asymmetric incentives, explains why the dispute persists despite both countries’ stated desire for resolution.

Regional and Broader Implications

The Yellow Sea dispute carries implications extending well beyond bilateral China–South Korea relations. How Beijing’s infrastructure campaign unfolds—whether successfully normalised or effectively challenged—will likely influence Chinese calculations in other disputed waters, including the East China Sea’s Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands and the Taiwan Strait.[lxiv] If grey-zone tactics succeed in establishing de facto Chinese control over the PMZ despite South Korean protests and alliance commitments, they may embolden similar approaches elsewhere. Conversely, effective pushback could demonstrate the limits of incremental expansion. The dispute also tests the credibility of US’ extended deterrence in the grey zone. If Washington proves unable or unwilling to support a treaty ally against ‘aquaculture facilities’ and coast guard harassment, it raises questions about alliance effectiveness below the threshold of armed attack.[lxv] More broadly, the case challenges the adequacy of UNCLOS and existing international legal frameworks for managing dual-use infrastructure, ambiguous sovereignty claims, and graduated coercion. The international community’s response—or lack thereof—to China’s PMZ activities may set precedents for how revisionist powers can exploit legal ambiguities and alliance gaps to incrementally alter maritime status quos, with significant implications for the rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific and beyond.

Future outlook

The Yellow Sea maritime boundary dispute remains fundamentally unresolved after 25 years of provisional arrangements, with the January 2026 summit offering limited progress on immediate symptoms while core legal disagreements persist. Three future trajectories appear possible: an optimistic scenario in which creative diplomacy produces phased solutions with transparency mechanisms; a most likely scenario of a managed stalemate with periodic crises and incremental Chinese gains; or a pessimistic scenario culminating in a Chinese fait accompli as structures normalise beyond the political or economic feasibility of removal. The outcome will depend on whether South Korea can leverage economic interdependence to extract genuine concessions, whether the United States clarifies its role in grey zone contingencies, and whether China calculates that accommodation better serves long-term interests than continued incrementalism. As the dispute illustrates, unresolved maritime boundaries create opportunities for patient revisionist powers to exploit legal ambiguities, alliance gaps and time itself as strategic weapons.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

[i] “China is Testing South Korea in the Yellow Sea”, The Economist, 15 January 2026.

[ii] David D. Lee, “Can China and South Korea Reset Complex Ties After Xi-Lee Summit?”, Al Jazeera, 6 January 2026.

[iii] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 10 December 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397, Art. 57.

[iv] “S. Korea Seeks Progress in Talks With China on Maritime Demarcation, Steel Structures”, The Korea Herald, 7 January 2026.

[v] “China is Testing South Korea in the Yellow Sea”, no. 1.

[vi] Victor Cha, “Creeping Sovereignty? China’s Maritime Structures in the Yellow Sea (West Sea)”, Beyond Parallel, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 9 December 2025.

[vii] “The Provisional Measures Zone and the Exclusive Economic Zones of the People’s Republic of China and South Korea”, Institute for the Study of War, 16 January 2025.

[viii] Yang et al., “Application Issues of Compulsory Conciliation in the Settlement of Fishery Disputes in the Yellow Sea”, Frontiers in Marine Science, Vol. 10, 2023.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] “The Role of Fishing Disputes in China–South Korea Relations”, The National Bureau of Asian Research, 23 April 2020.

[xii] Victor Cha, “Creeping Sovereignty? China’s Maritime Structures in the Yellow Sea (West Sea)”, no. 6.

[xiii] Seokwoo Lee and Clive Schofield, “The Law of the Sea and South Korea: The Challenges of Maritime Boundary Delimitation in the Yellow Sea”, The National Bureau of Asian Research, 23 April 2020.

[xiv] Victor Cha, “Creeping Sovereignty? China’s Maritime Structures in the Yellow Sea (West Sea)”, no. 6.

[xv] “S. Korea Seeks Progress in Talks With China on Maritime Demarcation, Steel Structures”, no. 4.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Suk Kyoon Kim, “Maritime Boundary Negotiations between China and Korea: The Factors at Stake”, The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, Vol. 32, 2017, p. 76.

[xviii] “S. Korea Seeks Progress in Talks With China on Maritime Demarcation, Steel Structures”, no. 4.

[xix] “China is Testing South Korea in the Yellow Sea”, no. 1.

[xx] Andrew S. Erickson, “How Gray-Zone Ops in the Yellow Sea Could Trigger a Maritime Crisis”, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Harvard University, 31 January 2023.

[xxi] “China is Testing South Korea in the Yellow Sea”, no. 1.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Terence Roehrig, “South Korea: The Challenges of a Maritime Nation”, The National Bureau of Asian Research, 23 December 2019.

[xxiv] Yang et al., “Application Issues of Compulsory Conciliation in the Settlement of Fishery Disputes in the Yellow Sea”, no. 8.

[xxv] “The Role of Fishing Disputes in China–South Korea Relations”, no. 11.

[xxvi] Seokwoo Lee and Clive Schofield, “The Law of the Sea and South Korea: The Challenges of Maritime Boundary Delimitation in the Yellow Sea”, no. 13.

[xxvii] “Chinese Platforms in the Yellow Sea’s South Korea-China PMZ”, Beyond Parallel, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 23 June 2025.

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] Victor Cha, “Creeping Sovereignty? China’s Maritime Structures in the Yellow Sea (West Sea)”, no. 6.

[xxx] “Chinese Platforms in the Yellow Sea’s South Korea-China PMZ”, no. 27.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] “China is Testing South Korea in the Yellow Sea”, no. 1.

[xxxiii] Ibid.

[xxxiv] Victor Cha, “Creeping Sovereignty? China’s Maritime Structures in the Yellow Sea (West Sea)”, no. 6.

[xxxv] “Chinese Platforms in the Yellow Sea’s South Korea-China PMZ”, no. 27.

[xxxvi] “China Expands in the Yellow Sea”, Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, 13 May 2025.

[xxxvii] “Chinese Platforms in the Yellow Sea’s South Korea-China PMZ”, no. 27.

[xxxviii] “China Issues No-Go Zone in Disputed Waters Claimed by US Ally”, Newsweek, 21 May 2025.

[xxxix] Victor Cha, “Creeping Sovereignty? China’s Maritime Structures in the Yellow Sea (West Sea)”, no. 6; “China, South Korean Vessels in 15-hour Yellow Sea Stand-off Last Month, Report Reveals”, South China Morning Post, 29 October 2025.

[xl] “China is Testing South Korea in the Yellow Sea”, no. 1.

[xli] Abhay K. Singh, “Expanding the Turbulent Maritime Periphery: Gray Zone Conflicts with Chinese Characteristics”, in Vikrant Deshpande (ed.), Hybrid Warfare: The Changing Character of Conflict, IDSA and Pentagon Press, New Delhi, 2018.

[xlii] “China is Testing South Korea in the Yellow Sea”, no. 1.

[xliii] Abhay K. Singh, “Expanding the Turbulent Maritime Periphery: Gray Zone Conflicts with Chinese Characteristics”, no. 41.

[xliv] David D. Lee, “Can China and South Korea Reset Complex Ties After Xi-Lee Summit?”, no. 2.

[xlv] “China–South Korea Relations”, Wikipedia.

[xlvi] “How Should South Korea Respond to China’s ‘Yellow Sea Project’?”, The Diplomat, 1 August 2025.

[xlvii] David D. Lee, “Can China and South Korea Reset Complex Ties After Xi-Lee Summit?”, no. 2.

[xlviii] “China Expands in the Yellow Sea”, no. 36.

[xlix] David D. Lee, “Can China and South Korea Reset Complex Ties After Xi-Lee Summit?”, no. 2.

[l] Ibid.

[li] “China is Testing South Korea in the Yellow Sea”, no. 1.

[lii] “S. Korea Seeks Progress in Talks With China on Maritime Demarcation, Steel Structures”, no. 4.

[liii] David D. Lee, “Can China and South Korea Reset Complex Ties After Xi-Lee Summit?”, no. 2.

[liv] Ibid.

[lv] “S. Korea Seeks Progress in Talks With China on Maritime Demarcation, Steel Structures”, no. 4.

[lvi] Suk Kyoon Kim, “Maritime Boundary Negotiations between China and Korea: The Factors at Stake”, no. 17.

[lvii] Victor Cha, “Creeping Sovereignty? China’s Maritime Structures in the Yellow Sea (West Sea)”, no. 6.

[lviii] Suk Kyoon Kim, “Maritime Boundary Negotiations between China and Korea: The Factors at Stake”, no. 17.

[lix] Ibid.

[lx] Victor Cha, “Creeping Sovereignty? China’s Maritime Structures in the Yellow Sea (West Sea)”, no. 6.

[lxi] David D. Lee, “Can China and South Korea Reset Complex Ties After Xi-Lee Summit?”, no. 2.

[lxii] Shuxian Luo, “China-South Korea Disputes in the Yellow Sea: Why a More Conciliatory Chinese Posture”, Journal of Contemporary China, Vol. 31, No. 138, 2022, pp. 1825–1842.

[lxiii] “The Role of Fishing Disputes in China–South Korea Relations”, no. 11.

[lxiv] Abhay K. Singh, “Expanding the Turbulent Maritime Periphery: Gray Zone Conflicts with Chinese Characteristics”, no. 41.

[lxv] “How Should South Korea Respond to China’s ‘Yellow Sea Project’?”, no. 46.