SHANTI Act and India’s Nuclear Energy Governance Framework

- February 17, 2026 |

- Issue Brief

Summary

The SHANTI Act 2025 is driven by the need to modernise India’s nuclear legal framework, strengthen regulatory institutions, and recalibrate liability to enable technological innovation and private participation.

On 15 December 2025, the Minister of State for Science and Technology, Dr Jitendra Singh, introduced the Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Bill, 2025, in Parliament, signalling a decisive shift in India’s nuclear energy governance framework. The Bill was subsequently passed by the Lok Sabha on 17 December 2025 and approved by the Rajya Sabha on 18 December 2025. With President Droupadi Murmu granting assent on 20 December 2025, the SHANTI Bill came into force as an Act of Parliament.[1] The 2026–27 budget announcement of customs duty exemptions on imports of input materials for nuclear power plants until 2035 is a building block for the passage of the SHANTI Act.

India’s nuclear energy capacity is 8.78 GW, accounting for approximately 3 per cent of the total installed electricity generation as of 2024–25.[2] Despite the substantial increase in the Department of Atomic Energy’s (DAE) budget and the expansion of nuclear capacity since 2014, nuclear power still forms a relatively small share of India’s energy mix.[3] The capacity is projected to reach approximately 22 GW by 2032, expand to 47 GW by 2037, and 67 GW by 2042, with a long-term vision of achieving 100 GW of nuclear power capacity by 2047.[4]

Looking ahead, nuclear energy is expected to provide a reliable baseload power source for emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), quantum computing, domestic semiconductor manufacturing and data-intensive research. Achieving these objectives necessitated a legal framework capable of supporting scale, investment and innovation, which the earlier statutes were structurally ill-equipped to fulfil. The SHANTI Act 2025 is driven by the need to modernise India’s nuclear legal framework, strengthen regulatory institutions, recalibrate liability to enable technological innovation and private participation.

By substituting the Atomic Energy Act (AEA), 1962 and the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act (CLNDA), 2010, the SHANTI Act establishes a unified legal framework designed to address India’s contemporary and future energy requirements. This brief contextualises the structural, regulatory and liability-related changes introduced by the SHANTI Act. It assesses their implications for India’s nuclear regulatory regime, particularly with respect to safety governance, private-sector participation and alignment with global nuclear norms.

Key Provisions

Private Sector Participation

The AEA, 1962, Section 3 vested complete authority over atomic energy in the Central Government, or any authority or corporation established by it, or a government company, for the production, use and disposal of atomic energy, thereby limiting the entry of private entities into the nuclear sector. In contrast, Clause 3 of the SHANTI Act significantly broadens the category of entities eligible to apply for a nuclear licence.[5] For the first time, the government has allowed ‘any other company’ under Clause 3(1)(c) or any other ‘person’ under Clause 3(1)(e) to apply for a licence to set up a nuclear facility, subject to strict regulatory oversight and state control.[6] The “‘company’ shall have the same meaning as assigned to it in clause (20) of section 2 of the Companies Act, 2013, but does not include a company incorporated outside India”. The “‘person’ shall include an individual or a company or association or body of individuals, whether incorporated or not, or the Central Government or a State Government”.

Under the license, the aforementioned entities under Clause 3(1) are eligible to ‘build, own, operate and decommission nuclear power plants or reactors’ [Clause 3(2)(a)], undertake limited nuclear fuel fabrication up to notified thresholds [Clause 3(2)(b)], and engage in the transportation and storage of nuclear fuel, spent fuel and prescribed substances [Clause 3(2)(c)].[7] These entities may also import, export, acquire, use or possess nuclear fuel, equipment, technology and software subject to government approval [Clauses 3(2)(d)–(f)].[8] Where activities involve radiation exposure, an additional safety authorisation is mandatory [Clause 3(3)].[9] Thus, the licensing regime under the SHANTI Act has significantly widened the regulatory scope compared to the earlier legal framework.

With regulated private and joint-venture participation in civilian nuclear activities, the SHANTI Act has simultaneously entrenched firm Central Government control over all strategically sensitive domains, including fissile material accounting [Clause 3(4)(a)], spent fuel custody and reprocessing [Clauses 3(4)(b) and 3(5)(b)], enrichment and isotopic separation [Clause 3(5)(a)], heavy water production and supervision [Clauses 3(4)(c) and 3(5)(c)].[10]

The involvement of private firms will help mobilise large-scale financial resources, reducing the burden on public finances while accelerating project execution through greater efficiency, adherence to timelines, and improved cost management.[11] It may also contribute to technological innovation and faster adoption of advanced reactor technologies, especially SMRs, by leveraging global partnerships. Collaborating with established public entities such as the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL) can synergise public-sector expertise in reactor operation and safety with private-sector strengths in capital investment, construction capability and supply chain management. It may help India’s Nuclear Energy Mission develop indigenous reactors, such as 200 MWe Bharat Small Modular Reactor (BSMR-200) and 55 MWe Small Modular Reactor (SMR-55), among others.

Additionally, private participation in areas such as plant construction, component manufacturing, temporary spent fuel storage and decommissioning could strengthen the overall nuclear ecosystem, create a competitive industrial base, and support long-term capacity expansion, while allowing the government to retain control over sensitive activities such as spent fuel reprocessing and strategic waste management. Private participation will also facilitate employment generation in India and prepare the nuclear sector for international markets, rendering it export-ready and potentially yielding significant revenue for India.

Liability Overhaul

The international nuclear liability law, the 1997 Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage (CSC),[12] establishes a two-tier compensation mechanism. First, liability is strictly and exclusively channelled to the nuclear operator (CSC, Annexe, Article 3).[13] The operator’s liability is capped at a minimum of 300 million Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) per nuclear incident. It must be backed by mandatory insurance or other financial security (CSC, Annexe, Articles 4 and 5). It is the responsibility of the Installation State to ensure the availability of 300 million SDRs or the amount it may have specified to the depository before the nuclear incident (CSC Article III).[14]

Second, if national compensation is insufficient to satisfy all claims for nuclear damage, supplementary compensation is provided through an international fund, contributed by Contracting Parties in accordance with a fixed formula (CSC, Article IV). As for the allocation of funds for compensation, it should be noted that 50 per cent of the international funds is to be used to compensate for damage suffered both within and outside the Installation State, while the remaining 50 per cent is to be used exclusively to compensate for transboundary damage.[15] Importantly, supplier liability is generally excluded, and the operator’s right of recourse is narrowly limited to cases where it is expressly provided for in a contract or where the damage results from an act or omission committed with intent to cause harm (CSC, Annexe, Article 10).

The CLNDA 2010 departed from international norms by introducing an expansive right of recourse against suppliers. Section 17(b) permitted operators to recover compensation from suppliers for latent defects or sub-standard services, even absent intent, and Section 46 preserved the possibility of tort claims under other laws. These provisions created legal uncertainty, discouraged foreign suppliers and were widely criticised as inconsistent with CSC. The SHANTI Act has aligned India’s nuclear liability regime with established international CSC practice while preserving robust victim compensation through a government-backed mechanism.

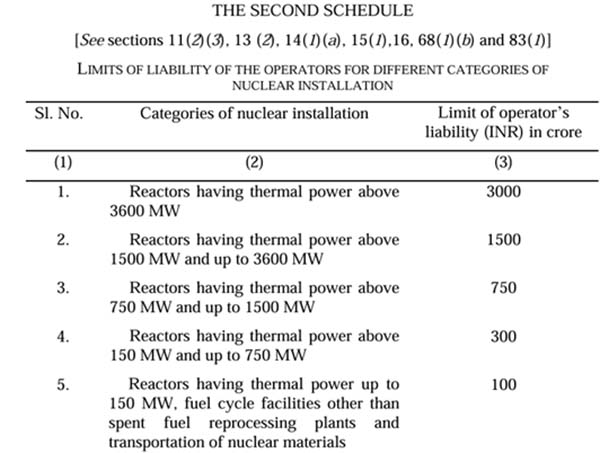

The SHANTI Act has adopted exclusive operator liability, fixed an overall liability ceiling of rupees equivalent to 300 million SDRs per nuclear incident or such amount as the Central Government specifies [Clause 13(1)], and introduced graded operator liability caps linked to reactor size as mentioned in the Second Schedule (see Figure 2). Beyond the operator’s Liability, the Act provides for the Central Government to establish a fund, the Nuclear Liability Fund (NLF), to address contingencies. Further, India’s participation in the CSC ensures that it can access international funds for compensation in the event of a nuclear incident. By restricting the operator’s right of recourse to situations involving express contractual agreement or intentional misconduct, the SHANTI Act has effectively ruled out automatic supplier liability.

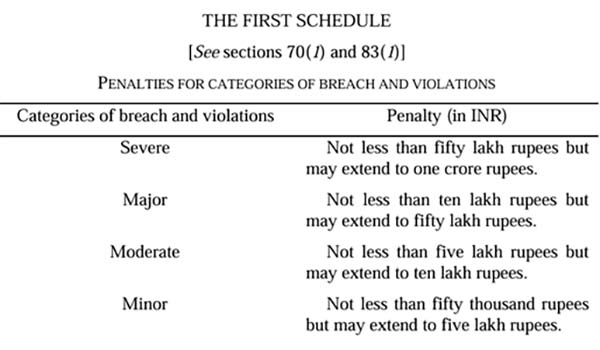

However, the Central Government is empowered under Clause 83(1) to periodically review and revise the penalty amounts in the First Schedule (see Figure 1) and the operator’s liability limits in the Second Schedule (Figure 2). This provision is designed to ensure regulatory adaptability in a sector characterised by rapid technological change and evolving safety standards. By allowing amendments to the liability caps and penalties based on factors such as advanced reactor technologies, enhanced safety features and risk profiles, Clause 83 prevents the law from becoming outdated or misaligned with contemporary realities. At the same time, because such amendments are confined to the Schedules rather than the core provisions of the Act, the clause balances administrative flexibility with legislative stability.

Source: The Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India Bill, 2025 (Bill No. 196 of 2025)[16]

Source: The Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India Bill, 2025 (Bill No. 196 of 2025)[17]

Statutory Status of The Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB)

The SHANTI Act has conferred statutory status on the AERB. Since 1981, there has been a demand to make the AERB a statutory body as per a report titled ‘Reorganisation of Regulatory and Safety Functions’. However, the AERB was created in 1983 through a government executive order.[18] Institutionally, the AERB reported to the Atomic Energy Commission and operated within the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE)’s administrative structure. Over time, experts noted that this arrangement limited perceptions of regulatory independence, as both the regulator (AERB) and the operator (DAE and its units, such as NPCIL) were within the same administrative system.

With the granting of statutory status, AERB’s institutional position changes fundamentally. Its powers, functions and organisational structure are clearly defined and protected by legislation, providing a firmer legal basis for regulating nuclear and radiation safety. This shift enhances its functional independence from the DAE and reduces concerns about institutional overlap between regulator and operator. Moreover, it can be seen as an impartial arbitrator to the foreign companies interested in investing in India’s nuclear sector.

The AERB exercises jurisdiction over licensing, safety authorisations, inspections, compliance orders and enforcement actions relating to nuclear installations and radiation facilities. It is empowered to issue binding directions, suspend or cancel licences and impose penalties for regulatory violations. The SHANTI Act further strengthens enforcement by empowering board regulators with inspection, investigation, search and seizure powers (Clauses 28–31).

Dispute Redressal Mechanism

The SHANTI Act has created a comprehensive, layered dispute-resolution mechanism to address potential disputes. If the concerned parties are not satisfied with the AERB’s decision, they may submit a review application to the Atomic Energy Redressal Advisory Council (AERAC) (Clauses 47–48), an expert review body exercising review and advisory powers rather than an adjudicatory authority. The Appellate Tribunal for Electricity [the Appellate Tribunal (Clauses 49–51)] established under Section 110 of the Electricity Act, 2003, serves as the specialised appellate forum for nuclear regulatory disputes, with authority to hear appeals against orders of the AERAC and penalties imposed under the Act. The Appellate Tribunal combines judicial authority with technical expertise, providing decisions that strengthen regulatory accountability and procedural certainty. If the concerned entities are dissatisfied with the Appellate Tribunal’s orders, they may appeal to the Supreme Court of India (Clause 52), which has jurisdiction over such orders.

Claims Commissioner and Commission

The Act provides for the Central Government to appoint a Claims Commissioner to administer compensation for nuclear damage to ordinary citizens. However, the appointment is now time-bound, occurring within 30 days of a notified nuclear incident. In the event of a large incident, the government may constitute a Nuclear Damage Claims Commission with a chairperson and up to six other members.

Promote Innovation, Research and Patents

To promote research and innovation in the nuclear sector, Clause 9 exempts certain activities from the licensing requirement. Activities related to research, development, design and innovation in the field of nuclear energy, henceforth, will not require a licence under Clause 9(1), except for activities of a sensitive nature, which are exclusively reserved for the Central Government. However, Clause 9(2) makes it clear that adequate safety measures should be adopted to protect persons, the public and the environment. This exemption reflects the Act’s intent to facilitate scientific and technological advancement by reducing regulatory burden. In addition, Clause 38 advances the patent regime for inventions in the peaceful nuclear energy sector, excluding sensitive activities, and delineates the procedure for granting patents in the nuclear field.

The SHANTI Act: Some Concerns

The nuclear sector is a sensitive topic in India, and traditionally, public perception regarding nuclear energy is not positive due to the potential consequences of a nuclear disaster, notwithstanding the low likelihood of such events.[19] Thus, several concerns remain regarding nuclear energy. First relates to the adequacy of the contingency funds allocated under the Act. The operator’s liability cap in India (at Rs 3,000 crore for large plants) is inadequate compared to disasters such as Fukushima, where total liability costs exceeded Rs 18,000 crore. However, the Fukushima accident was caused by a natural disaster: an earthquake that generated a tsunami. India’s nuclear programme places strong emphasis on site selection, seismic safety and layered regulatory oversight.[20]

Moreover, in addition to the operator’s liability fund, there exists the NLF and an international fund, as India has been a signatory to the CSC since 2010. The CSC operates on a reciprocal principle: members pay into the international fund when accidents occur in other member states and receive support when an incident occurs within their own territory.[21] Since the formulation of the CSC, no major nuclear incident has taken place that has required activation of the international supplementary compensation mechanism. However, when the government has to assume responsibility as an ultimate insurer—whether on account of inadequacy of the operator’s liability funds, the provisions of the Act (Clause 12 and Clause 14) or the exhaustion of the NLF, as well as the international fund—it will place a financial burden on public funds and taxpayers.

Second, the graded liability architecture in the Act may require review, as there is no direct correlation between reactor size and the extent of damage a nuclear accident may cause. The impact is influenced by factors such as location, population density, and the nature of the incident. Third, there is worry about the physical safety of nuclear reactors, especially during wars or conflicts. The SHANTI Act provides impetus for the construction of nuclear reactors, and in the coming years, India is expected to see a proliferation of them. The SMRs are likely to come up near densely populated civilian areas. In such a situation, can these reactors withstand a conventional enemy attack?

To begin with, India has demonstrated complete control over the country’s airspace through a robust air defence system, making it extremely difficult to breach. Next, countries are exploring new designs in which the outermost layer can withstand high-velocity impacts, such as intentional/accidental aircraft crashes or missile attacks.[22] Finally, compared with conventional reactors, SMRs have smaller core fuel inventories, resulting in lower short-term emissions during a nuclear emergency.[23]

Although there are norms that prevent states from attacking nuclear installations in other countries, they are often ignored during conflicts. In the ongoing Russia–Ukraine war, the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP) came under attack on a few occasions.[24] Similarly, in the past, countries have attacked under-construction nuclear plants in other countries. For example, Israel has attacked under-construction nuclear facilities in its West Asian neighbourhood, including Iraq, Syria and Iran in 1981, 2007[25] and 2025[26], respectively.

According to Article 56 of Additional Protocol I (1977) to the Geneva Conventions, nuclear power plants shall not be made the object of attack.[27] However, Article 56(2b) ceases to apply if a nuclear power plant directly and significantly supports military operations.[28] Thus, additional measures, such as constructing SMRs underground, may be explored to improve resilience against attacks and natural disasters, limiting radioactive releases even in extreme situations. However, the practical feasibility of such a solution remains uncertain due to cost and land-use constraints.

Fourth, there are environmental concerns regarding nuclear waste. However, this question is universal and not limited to India. If a country has used nuclear energy as a clean energy source since the 1950s, it must address its by-products. So far, India’s record on this count is robust, and even the SHANTI Act vests the power to take necessary measures for the safe disposal of radioactive wastes and to frame a National Policy for the Management of Spent Fuel and Radioactive Waste [Clause 32(1)(c)] with the Central Government. The Act has granted no powers to operators in this regard. These provisions indicate that the SHANTI bill itself recognises and attempts to address the associated risks.

Conclusion

Nuclear laws in India have always been shaped by the priorities of their time. The AEA addressed early concerns related to national security and sovereignty. In contrast, the inadequacy of compensation following major industrial accidents in India, such as the Bhopal Gas Tragedy, influenced the provisions that demand enhanced public accountability in the CLNDA. In the same vein, the SHANTI Act represents a policy adjustment rather than a radical break from past practice, addressing contemporary constraints in which rigid liability provisions have become a stumbling block to sectoral growth. By seeking a middle path between excessive state monopoly and unregulated private entry, the Act presents a balanced policy approach.

Major changes that the SHANTI Act has brought to the nuclear domain include facilitating private-sector involvement, aligning national liability laws with international standards, granting statutory status to the AERB, establishing a comprehensive dispute-resolution mechanism, and promoting innovation, research and patenting. However, this recalibration has raised concerns regarding the adequacy of contingency funds, the physical safety of reactors in the event of conflict, and environmental implications. The SHANTI Act has sought to address these concerns and can be amended to reflect evolving needs.

Niranjan Chandrashekhar Oak is a Research Analyst at MP-IDSA, and Bhawna Budhwar is a former Intern at MP-IDSA.

[1] “President Droupadi Murmu Grants Assent to SHANTI Bill Passed by Parliament During Winter Session”, News on Air, 22 December 2025.

[2] “The Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Bill, 2025”, Press Information Bureau, Government of India,19 December 2025.

[3] “Dr. Jitendra Singh Says SHANTI Bill Retains Strong Safety and Liability Safeguards Amid Lok Sabha Debate”, Press Information Bureau, Department of Atomic Energy, Government of India, 17 December 2025.

[4] “Parliament Passes SHANTI Bill, Atomic Energy Regulatory Board to Have Statutory Status”, DD News, 18 December 2025.

[5] “The Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India Bill, 2025”, PRS India, December 2025, p. 7.

[6] Ibid., p. 7.

[7] Ibid., p. 7.

[8] Ibid., p. 7.

[9] Ibid., p. 7.

[10] Ibid., pp. 7–9.

[11] “Road Map for Achieving the Goal of 100 GW of Nuclear Capacity by 2047”, Central Electricity Authority, Ministry of Power, Government of India, p. x.

[12] “Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage”, Information Circular, International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), 22 July 1998.

[13] Ibid., p. 29.

[14] Ibid., p. 6.

[15] “Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage (CSC)-Online Calculator”, International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

[16] “The Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India Bill, 2025”, PRS India, December 2025, p. 42.

[17] Ibid., p. 43.

[18] “Setting up of AERB”, Atomic Energy Regulatory Board, Government of India, p. 16.

[19] “A Report on The Role of Small Modular Reactors in the Energy Transition”, National Institution for Transforming India (NITI Aayog), Government of India, May 2023, p. 31.

[20] Jitendra Singh, “Transforming Energy into Strength: SHANTI’s Vision for Viksit Bharat”, Blog, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, 22 December 2025.

[21] “Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage (CSC)- Online Calculator”, no. 15.

[22] “Advanced Nuclear Plant Design Options to Cope With External Events”, International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), February 2006.

[23] Alvin Chew, “CO22036 | Nuclear Power Plants: Safe During War?”, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, 8 April 2022.

[24] “Update 220 – IAEA Director General Statement on Situation in Ukraine”, International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), 7 April 2024; “Ukraine’s Shelling Attack Near ZNPP Sets Fire to Dry Grass — Governor”, TASS, 12 August 2025; “Current Situation on ZNPP”, State Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate of Ukraine, Government of Ukraine, 5 March 2022.

[25] Ali Asghar Soltanieh, Katrin Mayer and Iva Sopta, “Armed Attacks on Nuclear Facilities: Historical Patterns, Legal Challenges, and Implications for Global Security”, Vienna International Institute for Middle East Studies, Article Number 11, December 2025.

[26] Kelsey Davenport, “Israel and U.S. Strike Iran’s Nuclear Program”, Arms Control Today, July–August 2025.

[27] “Protocol Additional to The Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to The Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), of 8 June 1977”, United Nations, p. 268.

[28] Ibid., p. 268.