Sir Creek in the Crosshairs: An Analysis

- November 17, 2025 |

- IDSA Comments

Historical Roots of the Dispute

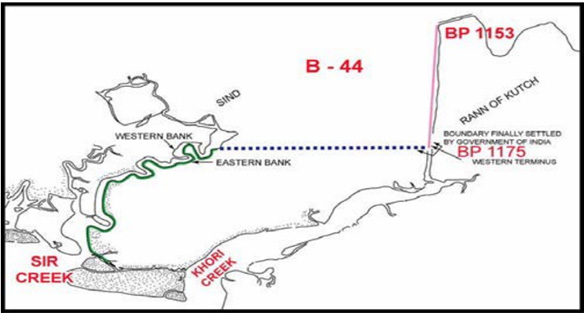

The Indus Delta, where the Indus River meets the Arabian Sea, is one of the largest river deltas in the world. It is a vast, fan-shaped region spanning about 600,000 hectares and comprising 17 major and several smaller creeks. It is rich in mangroves, fisheries and biodiversity, but also highly vulnerable to environmental change and sea-level rise. Sir Creek, a 96-kilometre-long tidal estuary within this delta, is a remote, sparsely populated and ecologically sensitive area that lacks major settlements or direct economic activity.[3] Before 1908, the Sir Creek region operated under an informal, largely peaceful administrative status quo. The Maharao of Kutch managed areas to the east of the creek, while Sindh, under the Bombay Presidency, oversaw regions to the west. The creek itself, then known as Ban Ganga, was used freely by local fishermen, and neither side had officially demarcated sovereignty over it.[4]

Source: Rear Admiral Hasan Ansari (Retd) and Rear Admiral Ravi Vohra (Retd), “Confidence Building Measures at Sea: Opportunities for India and Pakistan”, CMC Occasional Paper No. 33, SAND 2004-0102, Albuquerque, NM, Sandia National Laboratories, December 2003, p. 17.

In 1925, to implement the 1914 decision, boundary pillars were installed midstream, strengthening Kutch’s (and later India’s) case that the Thalweg principle was in practice. This arrangement continued until the Partition in 1947, when Kutch joined India and Sindh became part of Pakistan, converting an internal administrative line into an international border dispute. Between 1958 and 1961, both countries demarcated the boundary from Pillar No. 1 to Pillar No. 920. The demarcation process was suspended beyond Pillar 920, and tensions over the remaining stretch eventually escalated into the Rann of Kutch clashes of 1965

The intense fighting, though localised, began in early April 1965 between the Indian Army’s 31 Brigade, supported by artillery and armoured squadrons and the Pakistan Army’s 8 Division, along with Sindh Rangers and militia units, operating from bases in Badin and Hyderabad (Sindh) in the Kutch–Sindh sector. According to a CIA report, both India and Pakistan deployed over 5,000 soldiers each in the Rann of Kutch area during the fighting.[7] The UK’s mediation through Commonwealth channels led both countries to agree to a ceasefire and to submit the land dispute to international arbitration through the Indo-Pakistan Western Boundary Tribunal. In 1968, the Tribunal awarded about 90 per cent of the Rann to India and 10 per cent to Pakistan. However, it explicitly excluded Sir Creek from its jurisdiction, since, under international law, a tribunal cannot rule ultra petita (trans. beyond what is asked for), and the agreement did not address the resolution of the Sir Creek or the maritime boundary.[8]

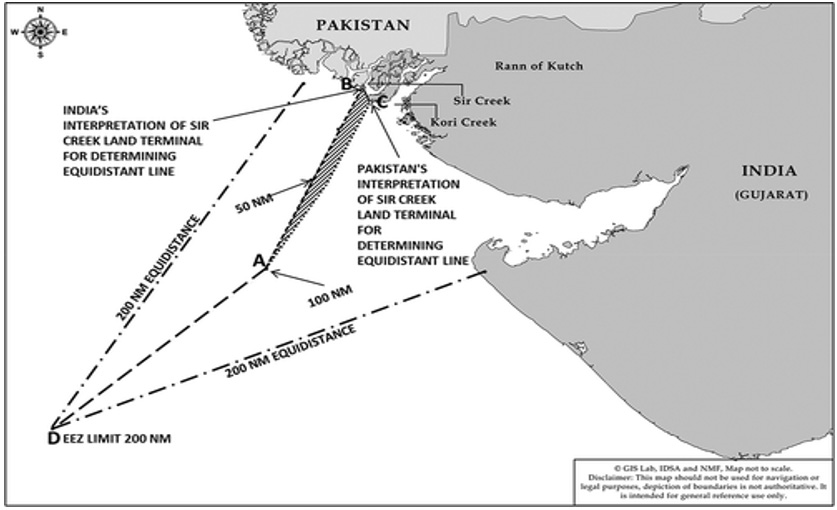

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS, 1982), every country’s maritime zones—including the Territorial Waters (12 nautical miles), Contiguous Zone (24 nm), and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ, 200 nm)—are measured from the point where its land boundary meets the sea, known as the land boundary terminus (LBT).[9] In the case of India and Pakistan, this point lies at Sir Creek, making its alignment crucial. Even a 2–3 kilometre shift east or west at the mouth of the creek can alter the starting point of the EEZ line. When projected 200 nautical miles (about 370 kilometres) into the Arabian Sea, it can translate into thousands of square kilometres of maritime territory. If the boundary runs midstream as India claims, the EEZ shifts westward, giving India a larger sea area; if it runs along the eastern bank as Pakistan claims, the EEZ moves eastward, favouring Pakistan (see Figure 2).[10]

Figure 2. Sir Creek Alignment and its Effect on the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)

Source: Raghavendra Mishra, “The ‘Sir Creek’ Dispute: Contours, Implications and the Way Ahead”, Strategic Analysis, Vol. 39, No. 2, 2015, p. 188.

Diplomatic Efforts

From 1989 to 1998, India and Pakistan held eight rounds of negotiations on the Sir Creek dispute as part of their Composite Dialogue process.[11] These discussions brought significant technical progress, including agreement on survey methods and historical documentation, but no political breakthrough. The main sticking points remained the same: Pakistan wanted the boundary fixed along the eastern bank, while India maintained that it should run midstream. After the eighth round in 1998, the dialogue was suspended amid rising political tensions, which included the nuclear tests conducted by both countries in May 1998 and the subsequent deterioration in bilateral relations. This period of strain was followed by the Kargil conflict in 1999 and a prolonged phase of frozen diplomatic engagement, effectively halting progress on the Sir Creek issue for several years.

The 2004 Islamabad Summit, which revived the Composite Dialogue, included Sir Creek among eight bilateral issues to be addressed through working groups.[12] This paved the way for renewed engagement and technical cooperation. Between 2005 and 2007, India and Pakistan conducted joint hydrographic surveys in the Sir Creek area. These surveys mapped the creek’s contours and identified fixed reference points that could serve as a basis for future demarcation. Foreign Secretaries Shyam Saran (India) and Riaz Khokhar (Pakistan) even discussed a trade-off formula during this period. Whichever country’s boundary line was accepted (India’s midstream line or Pakistan’s eastern bank line), that country would get 40 per cent of the sea area created by the new boundary. In comparison, the other country would get 60 per cent.[13]

Both India and Pakistan would then be able to share the economic benefits from the fishing and oil-rich waters, instead of one side losing completely. Such land–sea trade-off formulas are rare but not unique. Similar resource-sharing or median-line adjustments have been used in maritime boundary agreements between countries like Norway and Russia (Barents Sea)[14] and Malaysia and Thailand (Gulf of Thailand), where joint zones were created to avoid disputes and allow both sides to benefit.[15]

Despite the constructive phase of dialogue in the mid-2000s, progress on the Sir Creek issue stalled due to domestic political constraints in both countries. In Pakistan, the onset of the Judicial Movement in March 2007, which evolved into a nationwide political crisis, weakened President Pervez Musharraf’s authority and pre-empted his capacity to conclude bilateral agreements. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s proposed visit to Pakistan, initially planned for mid-2007, did not materialise, as the continuing political instability in Pakistan (2007–08) culminated in the end of Musharraf’s regime and was soon followed by the 26/11 Mumbai terrorist attacks in November 2008, which effectively froze the bilateral peace process.

Conclusion

The Sir Creek issue has been repeatedly overshadowed in successive rounds of India–Pakistan dialogue, particularly by the wider Kashmir issue. Over the past decade, India–Pakistan relations have further deteriorated following a series of major crises triggered by Pak-sponsored terrorism—the 2016 Uri attack, the 2019 Pulwama terror strike, and the 2025 Pahalgam attack, which prompted Operation Sindoor. After escalating tensions, India placed the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) on hold, signalling a reassessment of the water-sharing mechanism between the two countries. In retaliation, Pakistan declared the Simla Agreement “in abeyance” in April 2025, further deepening the diplomatic freeze.

Sir Creek may appear small on the map, but it determines where India’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) begins, directly influencing fishing, oil and gas exploration rights, and coastal security patrols in the Arabian Sea. Sir Creek—once regarded as the easiest of India–Pakistan disputes to resolve—continues to remain hostage to mutual distrust and recurring confrontations.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

[1] “Pakistan Expanding Military Infrastructure Near Sir Creek, Alleges Rajnath Singh”, Scroll, 2 October 2025.

[2] “Naval Chief Reviews Operational Preparedness in Creeks Area”, Dawn, 26 October 2025.

[3] “Sir Creek: Timeline of the India-Pakistan Dispute Over a 96 km-long Creek”, The Hindu, 8 October 2025.

[4] Shyam Saran, “The Sir Creek Story of a Chance Missed”, The Tribune, 8 October 2025.

[5] Ashutosh Misra, “The Sir Creek Boundary Dispute: A Victim of India–Pakistan Linkage Politics”, IBRU Boundary & Security Bulletin, Winter 2000–2001, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 91–96, Durham University, IBRU Centre for Borders Research, 2000.

[6] Shikander Ahmed Shah, “Without a Paddle”, Dawn, 23 February 2015.

[7] “India, Pakistan, and the Rann of Kutch”, Declassified Intelligence Memorandum, CIA-RDP79T00472A000400040020-2, April 1965.

[8] “The Indo-Pakistan Western Boundary (Rann of Kutch) Case, Award of 19 February 1968”, Reports of International Arbitral Awards, Vol. XVII, pp. 1–576, United Nations, 1969.

[9] “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)”, United Nations, 1982, Articles 5, 15, 74, and 83; see also “Baselines: An Examination of the Relevant Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea”, United Nations Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS), 1989.

[10] Raghavendra Mishra, “The ‘Sir Creek’ Dispute: Contours, Implications and the Way Ahead”, Strategic Analysis, Vol. 39, No. 2, 2015, pp. 184–196.

[11] Ashutosh Misra, “The Sir Creek Boundary Dispute: A Victim of India-Pakistan Linkage Politics”, no. 5.

[12] “Analysis of Pak-India Composite Dialogue”, IPRI Pakistan, 15 September 2015.

[13] Shyam Saran, “The Sir Creek Story of a Chance Missed”, no. 4.

[14] Thilo Neumann, “Norway and Russia Agree on Maritime Boundary in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean”, ASIL Insights, Vol. 14, No. 34, 10 November 2010.

[15] Sufian Jusoh et al., “Malaysia Joint Development Agreement”, Chinese Journal of International Law, 3 May 2023.