Tracing the Eastern Nagas’ Demand for Autonomy

- January 15, 2026 |

- Backgrounder

Summary

Following a year of tripartite talks among the Union government, Nagaland and the Eastern Naga People’s Organisation (ENPO), discussions on the Frontier Nagaland Territory Authority (FNTA) have made incremental progress. This Brief traces the evolution of the eastern Nagas’ demands for autonomy and examines the FNTA as a framework that seeks to accommodate tribal aspirations while maintaining Nagaland’s territorial integrity.

Introduction

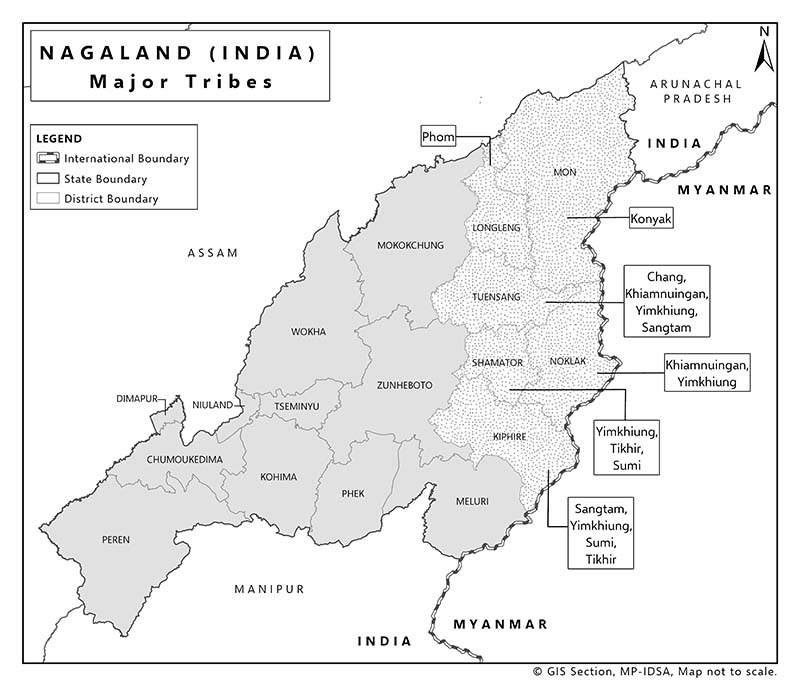

In the east of Nagaland lie six districts, namely Tuensang, Mon, Longleng, Kiphire, Noklak and Shamator, consisting of eight major Naga tribes—Konyak, Sangtam, Chang, Khiamniungan, Yimkhiung, Tikhir, Phom and Sumi (Figure 1). The tribals of these districts have highlighted identity disparity and systemic marginalisation from essential developmental processes by state authorities, often described as “step-motherly treatment”. These grievances underpin their demand for Frontier Nagaland Territory (FNT) as a separate state within the Indian Union, with its own state assembly, capital, Secretariat, High Court, Governor and Additional Director General of Police.

At the forefront of this is the Eastern Naga People’s Organisation (ENPO), which spearheads the demand for tribal autonomy for the eastern Nagas. Initially, the ENPO demanded the incorporation of the six districts of Eastern Nagaland, as well as two Naga-dominated districts of Arunachal Pradesh—Tirap and Changlang—into FNT, to address developmental and governance gaps. However, over the years, this demand has narrowed and is now restricted to the six Nagaland districts.

The Union government and the Nagaland state government, until recently, had been reluctant to accept these demands, as it would challenge and undermine the established political structure of Nagaland. Nevertheless, after years of negotiations, the Union government offered the formation of Frontier Nagaland Territory Authority (FNTA), a special arrangement for an autonomous region within Nagaland, crafted for the upliftment of the eastern Nagas—a process now in its final stages.

Source: GIS Section, MP-IDSA

Historical Context

In 1866, the British consolidated colonial rule in the Naga Hills. However, the six Eastern Nagaland districts—then collectively known as the Tuensang district—were declared an ‘Excluded Area’ due to their rugged terrain and the primitive practices of tribal communities, such as headhunting, which impeded the consolidation of British rule. Even after 1889, when the British first conducted expeditions to Tuensang, the area remained unadministered because they were unable to enforce political control fully. In 1929, the Naga Club submitted a memorandum to the Simon Commission, and, in accordance with its recommendation, the Naga Hills District was renamed the ‘Naga Hills Excluded Area’ in 1935.[1]

In 1937, when Burma was formally separated from India, the eastern Naga tribes were left divided between the two countries. They refused to join the Naga Hills as they claimed to have a distinct identity from that of the (present-day western) Naga tribes. In 1951, the Naga National Council (NNC) claimed to hold a ‘free and fair plebiscite’ and declared independence of the Naga Hills from India on the claim that 99.90 per cent Nagas voted for a ‘Free Sovereign Naga Nation’. However, the referendum’s validity was questioned by many, as the eastern Nagas of the then-Tuensang district had not voted. Even in 1954, Verrier Elwin reported that the tribals of Tuensang identified themselves as individual tribes, such as Konyaks, Changs, Phoms, and so forth, rather than as ‘Nagas’ as a whole.[2]

Tuensang, therefore, remained a separate administrative centre until 1948, when it was brought under the North Eastern Frontier Agency (NEFA) and named the Tuensang Frontier Division. Later in 1957, following the Naga Peoples’ Convention’s demand for statehood, which included the integration of only the Tuensang district of NEFA in the future Naga-state,[3] Tuensang was joined with the Naga Hills District of Assam and collectively renamed as Naga Hills Tuensang Area. In 1960, the 16-Point Agreement[4] was signed, followed by the formation of Nagaland as the 16th state of the Indian Union in 1963. Initially, the state was divided into three districts: Kohima (southwest), Mokokchung (central), and Tuensang (east). Over the years, Tuensang was further reorganised into six districts for administrative convenience.

As part of the 16-Point Agreement, Tuensang, due to its relative backwardness and underdevelopment, was designated a Regional Council under the aegis of the Governor of Assam under Article 371(A). It was under the Ministry of External Affairs’ control for 10 years, with an arrangement for an equitable allocation of funds between Tuensang and the rest of the state of Nagaland. In 1974, the special provision was abolished, and Tuensang was integrated as a full-fledged district with legislative representation.

However, the above provisional measure failed to achieve the intended objective of improving the economic and social status of the eastern Nagas; thereafter, they began to demand a separate state within the Indian Union. Therefore, while the east Naga tribes have advocated for ‘a peaceful Naga solution’, they have maintained a position distinct from the calls for ‘Greater Nagalim’ and related demands pursued by other Naga political groups.

Developmental Challenges

After the dissolution of the Council, the state authorities were to work towards the region’s development. However, alienation and a lack of socio-economic integration impeded the progress of Tuensang, as stated by tribal eastern Naga leaders (particularly the ENPO) on multiple occasions. The eight major hill tribes of Eastern Nagaland are often termed ‘backwards’ compared with the other ‘advanced’ tribes of the valley and a few others residing in the hills.[5] Their backwardness and the region’s underdevelopment have resulted from historical and geographical challenges.

Historical Neglect and Mis-governance

As reiterated by the ENPO, issues of negligence and mis-governance by state authorities have existed since the beginning, and have been further compounded by corruption and the misallocation of funds by government officials. This allegedly led to the alienation and underdevelopment of the eastern region while the rest of the state progressed.[6] Moreover, early ignorance of local eastern Naga leaders and a lack of representation in governance in later stages prevented them from fulfilling their obligations and resolving persistent issues.[7]

Inaccessible Terrain and Socio-economic Challenges

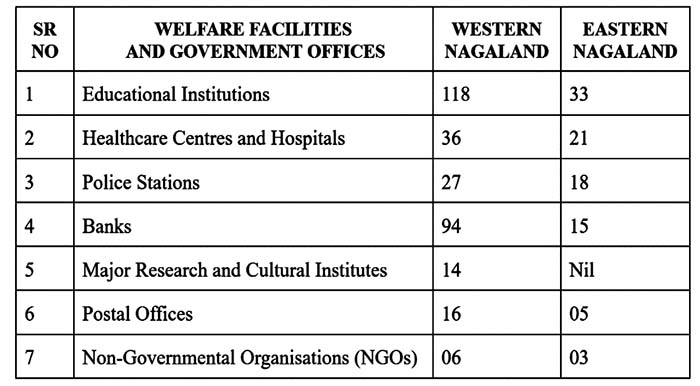

One of the significant impediments to Eastern Nagaland’s development has been its inaccessible terrain compared with Western Nagaland. While Western Nagaland is situated in the valleys and lower hill areas, Eastern Nagaland is characterised by tall, uneven hills, waterfalls and dense forests. Moreover, elevations range from a few hundred to nearly 4,000 meters, thereby making infrastructure construction and maintenance logistically and economically demanding. Thus, the lack of basic amenities, communication facilities and connectivity (Table 1) has induced large-scale poverty and migration and led to significant disparities in economic and educational backwardness between the eastern and western Nagas,[8] thereby fuelling discontent among the former.

Source: Data extracted from “Tuensang”, Government of Nagaland website and ENSF, “Why Frontier Nagaland? Eastern Nagaland Students’ Federation (ENSF) Explains”, Nagaland Tribune, 13 March 2024.

Political Under-representation

The ENPO also states a lack of representation of the eastern Naga tribes at the governance level. Firstly, while the 2011 census reports that the population of Eastern Nagaland’s districts is 28.8 per cent, the ENPO claims it is nearly 50 per cent, thereby demanding 40 of the 60 Legislative Assembly seats, compared with the current 20.[9] Secondly, government data indicate that the eastern Nagas’ contribution to state government services is approximately 20 per cent. However, the ENPO claims that the actual employment percentage remains stagnant at 3 per cent, despite a 25 per cent reservation policy for non-technical and non-gazetted posts.

Lastly, the tribes have also remained absent at the top level, including the Chief Ministerial and Presidential positions of the state and the Naga Students Federation (NSF), respectively, highlighting the lack of powerful representation to voice local demands. Former Chief Minister SC Jamir, Governor La Ganesan, and the current Chief Minister, Neiphiu Rio, have acknowledged and highlighted developmental gaps in Eastern Nagaland and have committed to undertaking corrective measures.

Timeline of Demands and Government Response

The demand for the separation of the eastern Nagas has been longstanding since independence. Additionally, due to backwardness and alienation, the eastern Naga tribes began formally rallying for the redress of their grievances through the formation of the Tuensang Mon People’s Organisation in 1994, which was later renamed the Eastern Naga People’s Organisation in 2005. In 2007, the ENPO passed a formal resolution for a separate state, the Frontier Nagaland Territory (FNT), and in 2010, a memorandum was issued to the Union government stating “the eastern Nagas’ incompatibility for continued co-existence with the other advanced groups”.[10]

Subsequently, in 2011, the state government constituted a high-level committee to review the demands, which recommended to the Union government the formation of four Autonomous District Councils (ADCs) under the Sixth Schedule, to be administered by the ENPO. This arrangement, as well as the state government’s Rs 500-crore and the Union government’s Rs 300-crore developmental assistance packages, were rejected by the ENPO. In 2015, the developmental packages offered by the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) were also dismissed by the ENPO, which remained adamant in its demand for FNT.

Between 2012 and 2017, discussions with the Union government continued, ENPO-led political advocacy and public outreach persisted, as did public demonstrations, but no major announcements or negotiations took place. Nevertheless, it exerted considerable influence on policy decisions. In 2017, it urged the Union government, through diplomatic channels, to encourage the Myanmar government not to fence Pangsha village in Noklak without consulting the ENPO and other eastern Naga tribal councils.

In 2017, the ENPO revived its demands, and the following year, the MHA agreed to discuss these. However, as discussions stalled over the next few years, the ENPO, in 2020, declared that it would not extend cooperation in any “national red-letter event” as a protest. Throughout 2021, internal meetings for tribal consensus on FNT continued to intensify, and a three-point resolution for non-cooperation with Indian security forces was also adopted as a response to the Oting incident.[11]

In 2022, through a high-level committee, the MHA initiated a formal dialogue with the ENPO to come to an agreed solution. However, the talks remained inconclusive due to the ENPO’s adamant demand for a separate state, which remains unacceptable to the Union government. On 26 August 2022, the ENPO convened a meeting and adopted a resolution to boycott the state elections scheduled for February 2023 unless the government met its demands for a separate state. As a result of the state government’s inaction, the ENPO boycotted the forthcoming state elections, demanded the resignation of the 20 Eastern Nagaland MLAs, and the Eastern Naga Student Federation (ENSF) organised a mass public walkathon.

In February 2023, however, the election boycott was withdrawn after Home Minister Amit Shah visited the state and assured that a solution would be implemented after the elections. As discussions continued in late 2023, the MHA submitted the highlights of the draft Memorandum of Settlement (MoS) to the Nagaland Chief Minister, requesting a response by 31 December 2023. However, the ENPO cited confusion regarding the authority—whether union or state government—from where the draft MoS had emerged, and raised questions on its content.

As a result of inconclusive FNT settlements, the ENPO, on 23 February 2024, adopted the Chenmoho Resolution calling for a boycott of the Lok Sabha elections and abstention from participation in electoral processes and national events/celebrations. Despite a clarification by the Nagaland Chief Minister, Neiphiu Rio, on 26 February 2024, that the MHA had indeed issued the MoS and that it could be received directly by the ENPO without the involvement of a third party, the ENPO rejected it. In refuting the claim that the ENPO had never received any such draft from the MHA, it blamed the state government for failing to meet the 31 December 2023 deadline to materialise the demand for a new state.

In March 2024, the ENPO declared a ‘public emergency’ and called for indefinite shutdowns in the six districts of Eastern Nagaland to put pressure on the Union government to acquiesce to its demands. In July, the ENPO held its Central Executive Council meeting, at which it decided to suspend the emergency to facilitate talks with the Union government on the creation of an autonomous territory. Negotiations and additional consultations continued through August and into September, with political and administrative details of the proposed territory being discussed.

In October, the Nagaland Cabinet reviewed the draft MoS-III and submitted its comments to the MHA in November. Consequently, in November 2024, the draft MoS-III was submitted by the Nagaland Chief Minister Neiphiu Rio to the MHA on behalf of the ENPO, thereby initiating a series of high-level tripartite meetings among the Union government, the state government, and the ENPO.

At its first meeting in December 2024, the Union government proposed the formation of the FNTA under Article 371(A), granting executive, legislative and financial powers to the eastern Nagas, a proposal that the ENPO temporarily accepted.[12] In the second meeting in January 2025, significant concerns regarding employment were addressed. In April, the EPNO agreed to temporarily narrow its demands, given the Union government’s inability to meet all of them.[13] The third meeting in July 2025 resolved contentious issues and prompted the MHA to demand clarity from the state government on certain financial and administrative matters.[14] These issues were discussed in the state cabinet in late August,[15] and the Chief Minister announced that a resolution to the ENPO-FNT demands was imminent.[16]

The fourth meeting in September 2025 concluded with the MHA assuring that a comprehensive draft on FNTA would be prepared at the earliest.[17] In November, the state government submitted revised comments to the MHA.[18] The fifth meeting was held in December 2025 to continue discussions on the matter.[19] Thus, the final talks have led to the suspension of the ENPO’s demands for a separate state and the acceptance of an offer for the formation of a unique autonomous, administrative set-up—FNTA—within the state of Nagaland. This is to be reviewed in 10 years, with the resolution of contentious matters undertaken through democratic political procedures.

Perspectives of Key Stakeholders

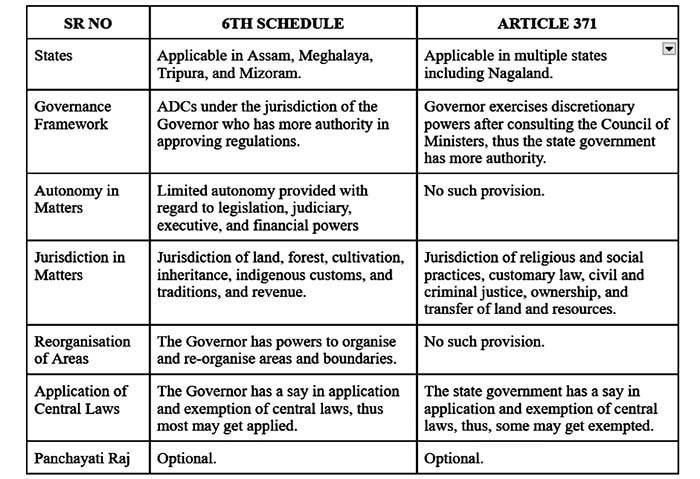

To understand these, it is essential to examine the differences between the provisions of Article 371 and those of the ADCs under the Sixth Schedule, the benefits they confer on the parties involved, and their impact on the Union and state governments (Table 2).

Source: Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “SIXTH SCHEDULE [Articles 244(2) and 275(1)]”, The Constitution of India, pp. 291–314 and India Code, National Informatics Centre, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, Government of India, “Part XXI.—Temporary, Transitional and Special Provisions.—Arts. 371-371A“, The Constitution of India, pp. 245–249.

ENPO

The ENPO has rejected developmental packages and various autonomous set-ups governed by the Sixth Schedule within the current state structure. Instead, it had demanded a separate state under a new sub-clause of Article 371 (distinct from that for Nagaland), rather than an alteration to Article 371(A). However, over the past couple of years, following numerous rounds of negotiations, the ENPO’s demand for a separate state has significantly diminished, leading to the acceptance of a special administrative system (FNTA) with limited autonomy under Article 371(A).

Union Government

Rejecting the ENPO’s demand for a separate state, the Union government has repeatedly offered financial packages and ARCs/ADCs under the Sixth Schedule, all of which have been rejected by the ENPO. Nevertheless, in the decades-old Naga insurgency, the Union government’s response to the ENPO’s demands has been markedly different from that of other Naga groups. Firstly, while underdevelopment and socio-economic isolation validate the ENPO’s demand for autonomy, the group has been non-violent in its means, often publicly denouncing bloodshed in its areas of influence. It has also put forth demands for intra-state regionalism, i.e., increased autonomy within the Indian Union, rather than complete geographical and political separation.

Moreover, contentious issues such as disputed history and borders, which lie at the crux of stalled negotiations with other Naga insurgent groups, are effectively absent in the case of the ENPO, thus making it feasible for the Union government to accommodate its demands. Secondly, the formation of FNTA—a special, negotiated set-up between the Union government and the ENPO—would reinforce India’s Act East Policy as it would give smoother access to the three International Trade Centres (ITCs) in Eastern Nagaland.[20]

Finally, as Eastern Nagaland lies between Myanmar, Arunachal Pradesh and Western Nagaland (certain areas of which host operational bases and logistical routes of other insurgent groups), the establishment of FNTA could create a buffer zone between these regions, serving as a viable border security measure in the country’s far east.[21] Therefore, through sustained security and political stability, FNTA has the potential to play a constructive role in building trans-border connectivity with Myanmar.

State Government

The state government’s overriding concern was its exclusion from the ENPO-FNT discussions (until 2024), as it feared being sidelined and voiced suspicions about matters discussed in its absence.[22] From the outset, the state government was not in favour of the ENPO’s demand for a separate state, given the eventual territorial bifurcation of the state. Although it has recommended the formation of ADCs, it may have expressed concerns about its reduced authority over fund transfers to FNT, which may be made directly rather than through the state government.[23]

Moreover, the state government initially opposed the introduction of a new sub-clause under Article 371, as initially demanded by the ENPO, which would have led to the article’s bifurcation.[24] This would have led to FNT’s removal from the existing state structure by creating a separate political identity for Eastern Nagaland, thereby affecting the state government’s governance framework. After multiple talks, however, these issues were resolved, and the state government decided to introduce changes “through a separate chapter, possibly via an ordinance or a State Act, to address matters outside the scope of Article 371(A)”.[25]

Civil Society and Tribal Groups

Although the eastern Naga leaders have consistently advocated for the ENPO’s demands, the lower-level cadres of the warrior tribe—the Konyaks—have been present within various insurgent groups, including several NSCN factions. This reflects the strategic leverage held by the Konyak tribal leadership, derived from its role in providing manpower to other insurgent groups, and from its ability to recalibrate this support if broader tribal backing for FNT demands is not forthcoming. Nevertheless, in addition to the individual eastern Naga tribal councils, various eastern Naga civil society groups, such as women’s organisations, student federations and government officers’ associations, have supported the ENPO’s demands.

Other Naga Political Groups

Although other Naga insurgent/political groups[26] have advocated for the ‘unification of all Naga-inhabited areas’, no major group, except the Naga National Political Groups (NNPG) and occasionally NSCN-IM,[27] has expressed reservations about the ENPO-FNT talks. However, both groups have often expressed expectations that ENPO will increase its involvement in the Naga peace talks. On the one hand, the NNPG has acknowledged the grievances of the eastern Nagas but has termed the FNT demands “antithetical to the ‘Indo-Naga’ political aspiration”.[28] It urged the ENPO to desist from making any arrangements that would devalue the Agreed Position (2017) signed between the Union government and the NNPG. It conveyed to the state government that it should not use the ENPO-FNT talks to divert attention from the impending Naga solution.

On the other hand, other groups, particularly NSCN-K/K2,[29] have held dialogues with the ENPO and expressed mutual respect and appreciation for each other’s contributions to advancing Naga unity and reconciliation.[30] These engagements have been undertaken in the hope of an early solution to the Naga issue, despite individual and territorial inter-tribal rivalries persisting amongst the eastern Nagas and other tribes. The NSF and ENSF have also supported each other’s endeavours and often collaborate to advance shared interests.

This support for the ENPO’s demands derives from the strategic and political significance held by the area inhabited by the eastern Nagas. As frontier districts bordering Myanmar that face cross-border insurgency, Eastern Nagaland holds immense geostrategic importance. It also carries significant economic weight owing to its vast geographical expanse of approximately 8,154 km² and abundant natural resources. Additionally, it carries political weight due to its large population and significant legislative seat share. These factors collectively strengthen the rationale for other groups to support the ENPO’s demands.

Conclusion

For decades, the eastern Nagas have demanded autonomy, highlighting years of neglect and alienation as reasons for Eastern Nagaland’s underdevelopment. While continuing to pursue non-violent means, they have remained determined to achieve the desired level of autonomy within the Indian Union, which has now taken shape as the FNTA. Over the years, the ENPO has managed to fraternise with its Naga political counterparts and also remained in amity with the Union government. As such, it has reiterated its support for a peaceful Naga solution while remaining sensitive to India’s national security challenges.[31]

The struggle of the eastern Naga tribes for achieving autonomy, by engaging various actors and voicing their demands through the consensus of a single, unified representative, appears to have culminated in a unique arrangement under the FNTA. Although the administrative and structural details of FNTA remain undisclosed, its significance as an arrangement designed to incorporate the demands and address the concerns of all stakeholders constitutes a sound case for accommodating tribal aspirations while maintaining the territorial integrity of the state of Nagaland. However, as negotiations to enforce the FNTA draw to a close, the long-term success of the framework will be demonstrated by the parties’ continued commitment, comprehensive monitoring of developments, and sustained tripartite engagement to address emerging challenges and ensure equitable outcomes.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

[1] K. Hokato Sumi and Kinitoli H. Yeptho, “The Movement for the Creation of Frontier Nagaland“, International Justice of Creative Research Thoughts, Vol. 13, No. 1, January 2025.

[2] M. Amarjeet Singh, “The Naga Conflict”, National Institute of Advanced Studies, 2012, p. 22.

[3] Pradeep Chhonkar, Quest for Nagalim: The Tribal Factor, KW Publishers, 2020, p. 59.

[4] “The 16 Point Agreement between the Government of India and the Naga People’s Convention”, UN Peacemaker, 26 July 1960.

[5] These hill tribes majorly include the Ao, Lotha and Angami tribes amongst others.

[6] Aniruddha Babar, “Frontier Nagaland Territory’s Legal Case for Direct Central Funding: Implications of Proposed Reforms“, The Morung Express, 8 September 2024.

[7] ENSF, “Why Frontier Nagaland? Eastern Nagaland Students’ Federation (ENSF) Explains”, Nagaland Tribune, 13 March 2024.

[8] “Why the ENPO Demands Frontier Nagaland“, The Morung Express, 30 January 2011.

[9] “Rio Makes Bold Statement on the ENPO’s Neglect Argument”, The Morung Express, 7 April 2024.

[10] Kameng Dorjee, “National Socialist Council of Nagaland’s Nagalim – Poison in the North East Region”, Arunachal Times, 10 April 2011.

[11] In December 2021, a counter-insurgency operation by Indian security forces in Nagaland’s Mon district led to the death of fourteen Konyak civilians who were suspected to be insurgents, thus sparking public outcry across the state.

[12] Bhadra Gogoi, “ENPO Temporarily Accepts Centre’s Offer for FNT”, The Times of India, 17 December 2024.

[13] “ENPO Agrees to ‘Frontier Nagaland Territory’ Offer with 10-year Caveat“, The Morung Express, 29 April 2025.

[14] “Third Tripartite Meet on FNT Resolves Key Issues: ENPO“, The Nagaland Post, 26 July 2025.

[15] “Nagaland Cabinet Reviews ILP Enforcement, ENPO Talks and Reservation Policy”, Nagaland Tribune, 6 August 2025.

[16] “Nagaland CM Neiphiu Rio Says Frontier Nagaland Territorial Authority Issue ‘Almost Resolved’“, Northeast Live, 29 August 2025.

[17] “Centre, State Govt, ENPO Hold 4th Tripartite Meeting“, The Nagaland Post, 10 September 2025

[18] “Revised and Updated Comments on Draft MOS-III for FNTA by State Government to MHA“, Department of Information and Public Relations, Government of Nagaland, 25 November 2025.

[19] “Centre Holds Tripartite Talks with ENPO on Frontier Nagaland Territory in Delhi“, Northeast Now, 22 December 2025.

[20] The three ITCs are Pangsha in Noklak, Lungwa in Mon and Mimi in Kiphire.

[21] Also refer to Pradeep Chhonkar, Quest for Nagalim: The Tribal Factor, no. 3, p. 198.

[22] “Nagaland Cabinet Reviews ILP Enforcement, the ENPO Talks, and Reservation Policy“, no. 15.

[23] Aniruddha Babar, “Frontier Nagaland Territory’s Legal Case for Direct Central Funding: Implications of Proposed Reforms”, The Morung Express, 8 September 2024.

[24] “State Opposes Any Move to Alter 371A for Frontier Territory: Kenye“, Nagaland Post, 7 August 2025.

[25] “Article 371A Will Not be Touched for the ENPO Demand: Nagaland Government“, NE Today, 17 October 2025.

[26] These include the NSCN-K factions, NNC factions and the Naga National Political Alliance (NNPA).

[27] Inter-tribal rivalries have existed between NSCN-IM and the ENPO. NSCN-IM’s Rh. Raising was criticised by the ENPO for terming the latter’s stance on its ‘Unity First, Solution Second’ principle as “nonsense”, for which he later apologised.

[28] “The ENPO Leaders Must Desist Arrangement That Seeks to Devalue Naga Political Aspiration: WC, NNPGs“, Nagaland Tribune, 25 July 2023.

[29] “NSCN/GPRN (Khango) Conveys Solidarity with the ENPO Demand“, Nagaland Post, 30 June 2023.

[30] “NSCN (IM) Leaders Meet the ENPO Delegation Over Naga Political Issue“, Eastern Mirror, 11 September 2020.

[31] The ENPO was the only Naga political group to publicly condemn the Pahalgam terror attack and express apprehension in response to a Bangladeshi official’s controversial statement on the occupation of India’s northeastern states.