Reifying Trumpian International Praxis: ‘Operation Southern Spear’ and Venezuela

- December 24, 2025 |

- Issue Brief

Summary

Venezuela is neither the primary source of the drug problem in the US, nor does the US need its oil in the near future. The scale of the military build-up, the level of expenditure, and the diplomatic stakes involved in initiating and sustaining Operation Southern Spear, keeping Venezuela at the centre, are disproportionate to the officially stated benefits.

US President Donald Trump has been the most significant disruptor of the established language and practices of diplomacy in the current global order. Since his second inaugural address in January 2025, he has consistently presented himself as a “President of Peace” and claims that his interventions and mediations have ended eight wars.[1] The claim, however, is disputed as no single definition or meaning of ‘war’ explains and validates it. Despite projecting an image of a peacemaker, he has also openly claimed territories in countries such as Canada, Denmark and Panama for the US on several occasions, without ruling out the use of force to achieve these goals.[2] Although not directly fighting at the front in Ukraine and the Israel–Gaza War, the US is involved in the dynamics sustaining the war. Trump has avoided direct involvement of US troops in any conflict and has shown reluctance to spend money on new wars. However, in the Caribbean Region, and in Venezuela in particular, Trump does not rule out the use of force to achieve his goals.

Trump has initiated a military build-up in the Caribbean Sea, claiming the actions to be against ‘narco terrorists’ in the region, especially from Venezuela, deploying US Navy and Air Force assets, including the largest Aircraft Carrier, Gerald Ford, several frigates and F-35s. He has ramped up the troop strength in the build-up to 11 US warships and 15,000 troops, declaring a war against ‘narco terrorists’, which has now been termed as the ‘Operation Southern Spear’.[3] At least 100 alleged ‘narco terrorists’ have been killed, reportedly in US strikes on 26 ‘suspected’ boats operated by drug cartels labelled as Foreign Terrorist Organisations (FTOs) and Specially Designated as Global Terrorist (SDGT).[4] Several of them were coming off the coast of Venezuela, allegedly carrying narcotics headed for sale and consumption in the US market.

Despite questions from national experts and international agencies and organisations, including the United Nations (UN), the Trump administration maintains that the strikes are legal.[5] Some international experts, however, have labelled the action as extrajudicial killings.[6] Also, the claim that the operation is against ‘narco terrorists’ has been rejected by Venezuela and Colombia most vociferously. Amid these developments, several other countries in the LAC region have raised concerns, fearing militarisation of the ‘Caribbean Zone of Peace’.[7] Therefore, Operation Southern Spear can be seen as a divergence from President Trump’s stated general disposition to withdraw the US from conflicts worldwide.

The developments have created tensions not only between Venezuela and the US but also in the Caribbean region. Venezuela has termed this use of force and strength as a part of a larger US design for regime change in the country. Trump, however, has attempted to brush off such criticisms, instead asserting that he was at war against narcotic supplies to the US from Venezuela. He also made public that the US Central Intelligence Agency had already been authorised to conduct operations in the country. Moreover, he has threatened land operations also, as the ‘narco terrorists’ are now avoiding the sea route due to the strong US presence and strikes against them.[8]

Amid these, there are speculations about President Trump’s motives and intentions regarding Venezuela. The development also appears to be Trump’s first serious push for regime change in another country. This brief, therefore, explains why Venezuela is being targeted at this juncture and what tangible benefits the US is expected to derive from it. For this, the two most stated reasons for Trump’s push—the US desire to control natural resources (especially oil) of Venezuela and the elimination of the drug problem in the US—have been investigated along with the Trumpian praxis and grand strategy of Making America Great Again (MAGA). The brief argues that the developments surrounding the launch of Operation Southern Sphere are not limited to Venezuela, they are part of the reified Trumpian international praxis, revealing the grand strategy that President Trump obscures through his unconventional statements.

Is Venezuela Responsible for the US Drug Crisis?

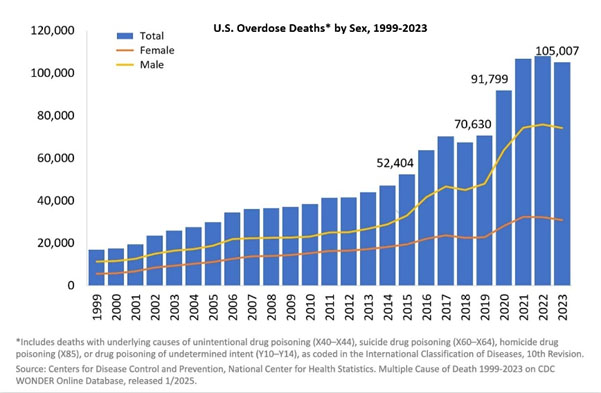

As per the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, National Centre for Health Statistics in the US data, the total number of drug overdose-related deaths for various reasons has consistently increased between 1999 and 2023. For reference, the total number of drug overdose deaths in 2015 was 52,404, which increased to a peak of 1,05,007 in 2022. The numbers declined slightly, but they were close to the 1,00,000 deaths recorded in 2023.[9] These are only the annual fatality figures, while the numbers impacted by the drug abuse problem are much higher. According to the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration survey, about 5.7 million people were suffering from opioid use disorder in 2023.[10]

Fentanyl is considered to be the prime source of drug overdose, as this synthetic drug is being mixed with counterfeit other medicines without the users knowing it. As Fentanyl is more lethal than other opioids, using it unknowingly in counterfeit drugs causes more cases of overdose. A study reported that Fentanyl had gradually replaced heroin in the drug supply chain.[11] Another more recent study has also observed a decline in the number of overdose deaths for several reasons, including the possibility of saturation of Fentanyl supplies and its replacement with other drugs since 2023.[12] However, the continuation of a decline cannot be guaranteed unless the US Government remains ever vigilant and proactive in its drug awareness, medical regulations and drug policing programmes.

President Trump had highlighted the problem in his domestic electoral campaigns, and the issue was part of Trump’s Agenda 47, which he promised to fulfil upon returning to the White House. Trump had taken the drug overdose deaths and trafficking seriously, even in his first term. Parts of the campaign for his second stint in the White House were built around his first term achievements of bringing drug overdose deaths down for the first time in three decades in 2017, contrasted with President Joe Biden’s term.[13]

Agenda47 also mentioned external and foreign policy steps to curb the problem, that President Trump will “impose a full naval embargo on the drug cartels and deploy military assets to inflict maximum damage on cartel operations”. He would also “insist on the full cooperation of neighbouring governments to dismantle the trafficking and smuggling networks in our region”. He had also exhorted that he would “tell China” to “clamp down on the export of fentanyl’s chemical precursors” or “pay a steep price”. He linked the drug crisis with border security and illegal Hispanic immigration through Mexico, including migrants from Venezuela.[14] Some of Trump’s policy interventions, along with fentanyl substitution and possibly supply saturation as well, have actually brought the overdose deaths down, reinforcing the seriousness of the Trump administration to “crack down on fentanyl smugglers, secure the US-Mexico border and execute drug dealers”.[15]

Venezuela does not produce Cocoa, the raw material for making cocaine, and most of the synthetic drug labs are located in the near-border regions of Mexico.[16] Only 5 to 10 per cent of the drugs that reach US soil are routed through the country.[17] Although the country is on a drug transit route, most of it is destined to European countries, and only a small part of it goes to the US.[18] Other countries like Mexico, Peru and Colombia have much bigger contributions to the US’ drug problem, and most of the drugs smuggled to the US enter through Mexico and the Eastern Pacific route rather than the Caribbean.[19] Fentanyl in the US is primarily sourced from across the southern border in Mexico.[20]

Yet, the US Trump administration has focused on Venezuela as if it were the epicentre of the drug problem in the region. President Trump has declared Nicolas Maduro, the President of Venezuela, as the leader of Cartel de los Soles (Cartel of the Suns), an informally coined term by the Venezuelan media in the 1990s to represent an alleged network of Venezuelan government officials, especially from the military, intelligence, judiciary and legislature of the country, involved in drug trafficking. The term, which derives its name from the sun insignia on the epaulettes of the Venezuelan military, was first used in 1993 when two generals of the Venezuelan National Guard had infamously gained traction in the popular imagination as well as the politico-strategic discourse, representing involvement of high-ranking government officials and members of the Venezuelan political elite in drug trafficking.

The US, however, chooses to call the Cartel de los Soles a drug-trafficking organisation. As per the allegations, Maduro helped manage the Cartel and is ultimately leading it.[21] Further, Maduro has allegedly helped and cooperated with the drug traffickers in Colombia and other countries in the region. The US had declared a reward offer of US$ 15 million for information leading to the arrest or conviction of President Maduro after a New York court charged him with drug-trafficking, possessing machine guns and destructive devices[22] in March 2020.[23] The reward after revisions is US$ 50 million. No other target under the anti-narcotics reward programme has a bounty exceeding US$ 25 million.[24]

In February 2025, the US government had declared several other transnational cartels operating in the Central and South American regions as Foreign Terrorist Organisations (FTOs) and Specially Designated Global Terrorist Organisation (SDGT), including Tren de Aragua, which had originated in Venezuela. Their operations are primarily located in Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia and Venezuela. The Trump administration has developed the designation of drug cartels as FTO and SDGT into a new tool to put pressure and take military action against these organisations. But, given Venezuela’s minimal role as compared to Mexico, Colombia and Peru in the US drug crisis, it is confounding to note that the US is justifying its heavy military build-up in the Caribbean Sea in the name of operations against narco terrorists.

Does the US Need Venezuelan Oil?

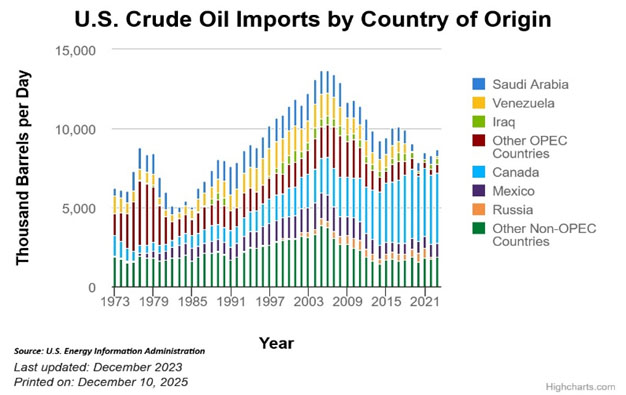

The US is currently the second largest consumer of energy in the world and was still recently dependent on petroleum imports, so much so that the oil import bill of the US had once had a significant (nearly 50%) share in its huge foreign trade imbalance.[25] Venezuela also had been a major contributor to the well-diversified US oil import basket in terms of its country of origin, along with others like Saudi Arabia, Mexico and Canada.[26] The trend of rising oil imports from Venezuela ceased, coinciding with the ascent of Hugo Chávez to the presidency and the peak in US oil imports in 2005. Until then, despite Chavez’s leftist rule, almost half of Venezuela’s total crude oil exports went to the US.[27] Since then, US oil imports have declined due to increased domestic production and reduced demand.

The shale revolution has enabled a rise in US domestic crude oil production, which had been in decline.[28] Notably, the US did not drastically or abruptly reduce or cut oil imports from Venezuela despite a leftist and critical Hugo Chavez ruling the country. With a consistent increase in domestic production, however, it gradually reduced the Venezuelan component from its import basket. The elimination of Venezuela from the basket also coincided with the US achieving self-reliance in terms of energy in general and crude oil in particular. The country has now become a net exporter of petroleum and energy, reducing its overall reliance on imports and thereby reducing the need to tap into neighbouring Venezuelan oil. The US has since preferred to replace crude supplies from Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, and other oil-exporting countries (OPEC) with increased imports from neighbouring Canada.

Venezuela had been a consistent and significant source of crude oil for the US since the 1920s, to such an extent that US southern Gulf Coast refineries structured and specialised in refining the heavy, sour crude from there. In the absence of the shale revolution, global oil production was also peaking at the end of the first decade of the 21st century.[29] Therefore, Venezuela, with the world’s largest proven crude oil reserves, was a lucrative option for the US to explore and, if possible, secure for its consumption. Venezuelan crude oil production peaked in 1970 and subsequently declined due to the maturation of light crude fields and structural changes in the country’s oil industry.[30] Production recovered in the 1990s, reaching close to the previous peak but not surpassing it.[31]

The economic, political and ideological dynamics within the country from the late 1990s led to a steady decline in crude production.[32] Nationalisation of oil production, reduced investment and ideological differences with the US emerged during the Chavez era.[33] The convergence of the rise of the anti-US leftist Chavez government in Venezuela with the shale oil revolution both instigated and allowed the US to put pressure on the country through sanctions as it shifted to domestic production and other sources rather than depending on the supplies from the increasingly hostile and politically uncertain Venezuela. Based on import-export data, it appears that the US does not require Venezuelan crude at least in the medium term, as it has deliberately reduced imports and subsequently blocked Venezuelan oil from the market.

Neither Drugs nor Oil, Then? Oil!

The Barack Obama administration imposed the first set of sanctions on Venezuela, blaming it for not cooperating in the US anti-drug and counter-terrorism operations in 2006. All US arms sales and transfers were prohibited in the first round. The sanctions were further expanded in 2008, 2014 and 2015; first imposing financial restrictions on specific Venezuelan individuals and agencies who were allegedly helping Hezbollah in Lebanon, then targeting individuals responsible for human rights violations and anti-democratic oppression. In 2015, President Obama signed an executive order imposing visa restrictions on identified Venezuelan officials for undermining democratic institutions and human rights abuses. The assets of such individuals could also be blocked under the order. The sanctions were political in their dimensions and targeted only individuals and a few agencies rather than the country as a whole.

Relations between the two countries have further deteriorated since President Trump’s first stint in the White House. Since 2017, barring a brief relaxation during President Joe Biden, the Trump administration has expanded the sanctions to the country as a whole, targeting its economy, primarily petroleum, mining, gold, food subsidy and banking sectors. The oil sector appears to be the primary target, as Trump also prohibited Venezuela’s access to the US financial markets and blocked oil dividends.[34] He has sanctioned blockaded oil tankers serving Venezuela and recently ordered the seizure of a vessel full of crude oil, the “largest one ever, accused of violations by carrying Venezuelan oil”.[35]

The most recent set of restrictions on Venezuelan entities includes sanctions on six more oil tankers and shipping firms linked to them, together with three relatives of President Maduro’s wife, labelling them as “narco nephews” of President Maduro.[36] These developments and an ‘advice’ by President Trump that President Maduro “must leave the country now”[37] indicate that Operation Southern Spear is dropping the veil of anti-narco terrorism to depose an ideological irritant in the neighbourhood. The flight of the underground Venezuelan right-wing Leader of opposition, Maria Machado, to Norway with the help of a former US special forces operative strengthens the theory of a serious push for regime change in Venezuela. Shortly after Maria’s appearance in Sweden, Trump indicated that the US is going to start land strikes on Venezuela. This may not be a coincidence as it squeezes Venezuela further, raising US hopes for an internal rebellion against Maduro, forcing him to leave ultimately.

The stage is almost set for a regime change, except for a direct US military operation against Venezuela. These are testing times for Maduro’s supporters and his patrimonial institutional arrangements, as the US CIA is already authorised to operate with specific goals. US drug overdose is already declining due to extraordinary efforts made by the Trump administration, along with other factors, so why this massive military effort? Is it to eradicate the US drug crisis once and forever? If so, why not designate Mexico, Colombia and Peru as the central targets of the Operation? The answer may lie in the US long-term oil prognosis and its grand strategy shaped by Trumpian ideology and praxis.

The oil import-export data reveal that, as domestic oil production has increased, the US has deliberately weaned itself away from Venezuelan crude and sanctioned the country’s oil industry. It seems, therefore, that the US does not need Venezuelan oil urgently or in the medium term as it has diversified sources of supply. However, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) recently projected that the shale boom will fade and that oil production will peak by 2027.[38] Efficient use and management of oil resources may slightly extend the limit, but domestic oil production is projected to decline after 2030.[39] It means that the US cannot ignore Venezuela’s proximity, lower costs (due to discounted prices and ease of transport), and its largest proven oil reserves forever.

There is a narrow window for it to strategise in the medium term and secure uninterrupted access to Venezuelan crude in the future, thereby stabilising the energy market in line with its needs and sustaining its economic pre-eminence and global power. The oil and resource dimension in the US strategy appears significant, although it is obscured by other narratives, given the rise in US domestic crude production. President Trump’s and his aide Stephen Miller’s recent rhetoric alluding to the fact that Venezuelan oil belongs to Washington reveals the oil angle behind the whole exercise.[40]

Regional and Global Dimensions of Operation Southern Spear

Trump has already expanded the scope of US military actions by warning Colombia. A couple of the strikes on allegedly narco-trafficking boats have been conducted near the country, and almost half of the total in the Eastern Pacific, which is far from Venezuela. The two most recent US strikes on suspected narco-boats killing 8 and 4 onboard also took place in the Eastern Pacific.[41] Operation Southern Spear appears to have a regional scope rather than being limited to Venezuela, as evidenced by the war of words between the US and Venezuela. Although the military build-up is in the Caribbean Sea, the strikes against the so-called narco-boats are spread up to the Pacific side of the region, the primary drug route to the US. The strikes are well spread beyond Venezuela.

The primary focus of the political statements, however, is Venezuela, despite not being a major contributor to the drug problem. Colombia is the second focus of the statements, and the two countries share one factor: a left-oriented government that lends an ideological dimension to the goals of the military build-up. Colombia may not be an immediate target as the Trump administration might be hoping the ouster of its leftist President Gustavo Petro through democratic processes in the country, as it has not transformed into a leftist dictatorship, as has been the case in Venezuela from the US viewpoint. The Trump administration does not perceive democratic change and a pro-US government within Venezuela anytime soon, thereby pushing for military pressure and gunboat diplomacy.

The Trump administration has recently released the National Security Strategy (NSS) 2025, which outlines a framework to make sense of the chaos and obfuscation created by Trump’s statements and seemingly undiplomatic behaviour. The document is inspired by the US ideology of economic and military ‘domination’ clad with the Trumpian cloak of “Peace Through Strength”. The emphasis on peace could be interpreted as the US’s desire to avoid “forever wars” and to focus on its strengths to first eliminate competition and contention in the neighbourhood. The Trumpian worldview and international praxis reflect a 19th-century US, which began to rise as an unprecedented superpower, starting with its dominance in the Western Hemisphere.

Trumpian praxis imitates the same and has already begun its strategic counter-offensive against perceived revisionist powers (China) and actors challenging its global dominance. It started with the assertion and subsequent implementation of a ‘Trump Corollary’ to the Monroe Doctrine in the Western Hemisphere. In this context, Venezuela can be seen as a test case for the actual meaning and enactment of the stated principles of “peace through strength”, “predisposition to non-interventionism”, and “sovereignty and respect” in the NSS 2025 towards achieving the US “dominance” in the Western Hemisphere first and then in the global order.

Conclusion

Venezuela is neither the primary source of the drug problem in the US, nor does the US need its oil in the near future. The scale of the military build-up, the level of expenditure, and the diplomatic stakes involved in initiating and sustaining Operation Southern Spear, keeping Venezuela at the centre, are disproportionate to the officially stated benefits. The gap between goals and the scale of the US military activity in the Caribbean, together with the statements made by President Trump against the Maduro regime, was difficult to understand until the release of the NSS 2025. The document dispels speculation and clarifies the reification of the Trumpian praxis and global outlook that countries, their leaders, and scholars worldwide have sought to understand. It places the Western Hemisphere at the centre of Trump’s global strategy to reassert US dominance. It also puts in perspective the statements and actions by Trump 2.0 in the Latin American Region and reveals a concrete strategy behind the fog of unpredictability that his statements create.

The US has decided that a favourable government in Venezuela is a must. Although the left-ruled Colombia is a bigger source of the US drug crisis, it does not have the oil that Venezuela has, which the US would need in the foreseeable future. Trump’s imaginings of the global order and US dominance are shaped by his nostalgic and ideological attachment to 19th-century Western Hemisphere dominance and the rise of the US as a superpower. The strategy is an attempt to Make America Great Again by repeating history with the initiation of the ‘Trump Corollary’ to the Monroe Doctrine. Trump’s Operation Southern Spear is implementing the Corollary, and, in its design and utility, it is not limited to Venezuela. The regional action is part of a broader global strategy aimed at US economic and military dominance.

Data reveals that President Trump is serious about his anti-drugs campaign, and the strikes in the Eastern Pacific can be linked to that. However, he wants to hit multiple targets with one stone, i.e., terrorising the drug cartels, pressurising and removing ideologically disagreeing leadership in the Western Hemisphere, exclusion of external influence in the region (especially China) and implementation of the ‘Trump Corollary’ to the Monroe Doctrine towards the US’s regional and global economic and military dominance. The questions regarding legally dubious strikes on boats and targeting Venezuela rather than Colombia or Mexico for the drug problem are part of the Trumpian ideology and global praxis. Venezuela is merely the beginning of a strategy that is reified and unfolding.

[1] Message by President Donald Trump, National Security Strategy 2025, p. i.

[2] Selwyn Parker, “Trump Goes Deep into the Panama Canal”, The Interpreter, 14 January 2025; Grant Wyeth, “The Practical Obstacles to Canada as the 51st State”, The Interpreter, 14 January 2025.

[3] Anthony Blair, “11 US Warships and 15,000 Troops Now in Caribbean as Venezuela Tensions Escalate”, New York Post, 30 November 2025.

[4] “US: Military Boat Strikes Constitute Extrajudicial Killings”, Human Rights Watch, 16 December 2025; “US Military Kills Eight in Strikes on Alleged Narco-trafficking Vessels in Eastern Pacific”, France 24, 16 December 2025; Kevin Doyle, “US Kills 4 in Latest Pacific Ocean Attack as Venezuela Tension Spirals”, Al Jazeera, 18 December 2025.

[5] “US Strikes in Caribbean and Pacific Breach International Law, Says UN Rights Chief”, United Nations, 31 October 2025.

[6] “US: Military Boat Strikes Constitute Extrajudicial Killings”, Human Rights Watch, 16 December 2025.

[7] Lyndal Rowlands, “US Confirms Four People Killed in 20th Strike on Vessel in the Caribbean”, Al Jazeera, 15 November 2025.

[8] “Donald Trump Says Land Strikes on Venezuela Coming ‘Soon’”, News Week, 12 December 2025; “Trump Says Venezuela Land Strikes “Going to Atart,” Maduro Condemns “Fools in the North””, Global News, 14 December 2025.

[9] “U.S. Overdose Deaths by Sex, 1999-2023”, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2 December 2025.

[10] “What is Opioid Use Disorder?”, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2 December 2025.

[11] D. Ciccarone, “Fentanyl in the US Heroin Supply: A Rapidly Changing Risk Environment”, International Journal of Drug Policy, Vol. 46, 2017, pp.107–111.

[12] Deborah Dowell, Nisha Nataraj, Michaela Rikard, Joohyun Park, Kun Zhang and Grant Baldwin, “Why Have Overdose Deaths Decreased? Widespread Fentanyl Saturation and Decreased Drug Use Among Key Drivers”, The Lancet Regional Health – Americas, Vol. 51, November 2025.

[13] “Agenda47: Ending the Scourge of Drug Addiction in America”, Trump-Vance Make America Great Again 2025, 6 June 2023.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Trump’s Punitive Approach to Drug Addiction is Nothing New”, Time, 10 February 2025.

[16] National Drug Threat Assessment 2025, Drug Enforcement Administration, US, pp. 21–31.

[17] “What is Driving US President’s Trump’s Actions Against Venezuela?”, Al Jazeera, 30 November 2025; “Facts to Inform the Debate About the U.S. Government’s Anti-drug Offensive in the Americas”, The International Drug Policy Consortium (IDPC), 3 November 2025.

[18] “Facts to Inform the Debate About the U.S. Government’s Anti-drug Offensive in the Americas”, no. 17.

[19] Ibid.

[20] National Drug Threat Assessment 2025, Drug Enforcement Administration, US, pp. 21–31.

[21] “Nicolás Maduro Moros”, U.S. Department of State, 7 December 2025.

[22] “Cartel de los Soles | Mission Maduro”, The Hindu, 7 December 2025.

[23] “Nicolás Maduro Moros”, no. 21.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Robert D. Blackwill and Meghan L. O’Sullivan, “America’s Energy Edge: The Geopolitical Consequences of the Shale Revolution”, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 93, No. 2, p. 109; James K. Jackson, “U.S. Trade Deficit and the Impact of Changing Oil Price”, RS22204, Congressional Research Service Report, February 2020.

[26] “U.S. Crude Oil Imports by Country of Origin”, Alternative Fuels Data Center, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, U.S. Department of Energy, December 2023.

[27] “Venezuela’s Chavez Era: 1958-2013”, Council on Foreign Relations, 10 December 2025.

[28] Robert D. Blackwill and Meghan L. O’Sullivan, “America’s Energy Edge: The Geopolitical Consequences of the Shale Revolution”, no. 25; “The United States Has Been an Annual Net Total Energy Exporter Since 2019”, U.S. Energy Information Administration, 17 December 2025.

[29] Robert D. Blackwill and Meghan L. O’Sullivan, “America’s Energy Edge: The Geopolitical Consequences of the Shale Revolution”, no. 25, p. 102.

[30] “Venezuela’s Oil Production Over Time”, Reuters, 11 December 2025.

[31] Robert Rapier, “Charting the Decline of Venezuela’s Oil Industry”, Forbes, 29 January 2025.

[32] Ibid.

[33] “How Venezuela Ruined Its Oil Industry”, Forbes, 7 May 2017.

[34] “Venezuela: Overview of U.S. Sanctions Policy”, Congressional Research Service Report, 5 December 2025; “Venezuela Related Sanctions”, U.S. Department of State, 17 December 2025.

[35] Kayla Epstein and Lone Wells, “US Seizes Oil Tanker Off Venezuela as Caracas Condemns ‘Act of Piracy’”, BBC News, 11 December 2025.

[36] “US Slaps Sanctions on Maduro Family, Venezuelan Tankers: What We Know”, Al Jazeera, 12 December 2015.

[37] Tom Phillips, “Trump Reportedly Gave Maduro Ultimatum to Relinquish Power in Venezuela”, The Guardian, 1 December 2025.

[38] Shariq Khan, “US Oil Production to Peak by 2027 as Shale Boom Fades, EIA Forecasts”, Reuters, 16 April 2025.

[39] Ibid.

[40] “Trump Again Demands Venezuela ‘Return’ Assets to US”, China Daily, 18 December 2025.

[41] Kevin Doyle, “US Kills 4 in Latest Pacific Ocean Attack as Venezuela Tension Spirals”, Al Jazeera, 18 December 2025; “Video: US Military Strikes 3 Suspected Drug Boats in Eastern Pacific, 8 Killed”, Marine Insight, 17 December 2025.