Decline of Left Wing Extremism in India

- November 18, 2025 |

- Issue Brief

Summary

The Union Government has vowed to eliminate Left-wing extremism by March 2026. Several significant developments, including the recent elimination or surrender of key Maoist leaders, will no doubt help the government achieve this objective.

Introduction

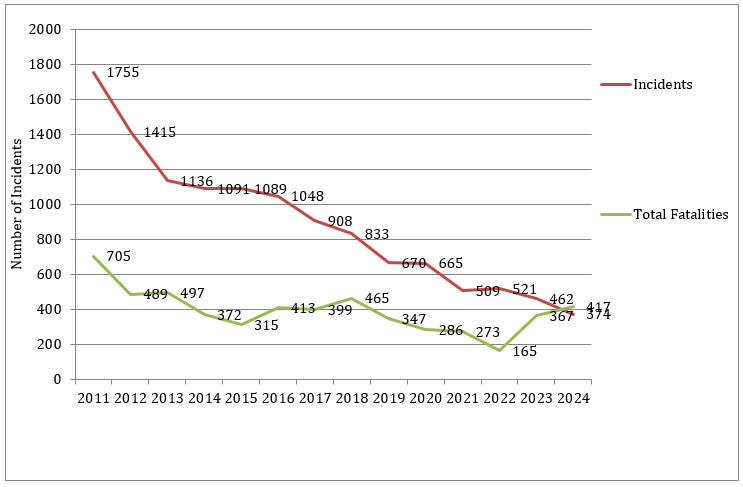

The communist insurgency has been one of the most potent threats to India’s internal security for nearly seven decades. The peak of Maoist violence in 2010 was followed by a persistent decline in insurgency (in terms of the number of violent incidents and deaths) in India since 2011. The Union Government’s decision to set March 2026 as the deadline for the complete elimination of Left-Wing Extremism (LWE) reflects a new sense of confidence towards the eradication of left-wing extremism in India.

Several significant developments on the ground have brought this renewed optimism. The killing of Nambala Keshava Rao (Basavaraju), the General Secretary of the Communist Party of India (Maoist), in May 2025, delivered one of the most serious setbacks to the organisation in recent years. Also, in October 2025, Mallojula Venugopal Rao, a senior member of the Politburo and the Central Military Commission, chose to surrender, signalling profound fatigue and a loss of morale within the Maoist ranks.

In addition to these developments, the Ministry of Home Affairs announced in the same month that the number of LWE-affected districts had come down from 18 to 11, and the ‘most affected’ districts had reduced from 6 to 3 (Sukma, Bijapur and Narayanpur). Together, these developments suggest that the Maoist movement is shrinking both in territorial reach and ideological influence.

The year 2004 marked a turning point in the Maoist movement with the formation of the Communist Party of India (Maoist) through the merger of the People’s War Group and the Maoist Communist Centre of India. This unification further expanded the Naxalite uprisings, compelling the Union Government to adopt a coordinated and comprehensive counter-insurgency strategy. This brief highlights the key policy initiatives of successive central governments since 2004 towards eliminating LWE.

UPA Government’s Approach to LWE

The Maoist movement in India took shape amid longstanding social and economic inequalities, especially in tribal and rural areas burdened by poverty, land alienation and exploitation by local elites. Years of weak administration, uneven development and lack of proper implementation of land reforms deepened public resentment and provided space for mobilisation. Drawing strength from these grievances, the Maoists advanced the issue of tribal rights and justice, framing their armed struggle as a fight against state neglect and social injustice.

Amid growing unrest, the government gradually recognised that the movement could not be addressed solely through coercive measures and that a deeper engagement with its socio-economic dimensions was required. The Manmohan Singh government viewed LWE primarily as a reflection of socio-economic deprivation and tribal alienation rather than a purely law-and-order issue. Therefore, its overarching approach for tackling the LWE threat was a ‘development-first’ strategy.

It sought to do so through devolving political power at the grassroots through the implementation of the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 (PESA), as well as by enacting the Forest Rights Act, 2006 (FRA).[1] The aim here was to empower local tribal and non-tribal communities to control natural resources, secure land rights and enhance participatory governance in Scheduled Areas. Alongside this, the government also followed a measured security approach—modernising police forces, improving state capacities and deploying central paramilitary forces in LWE-affected states in a supportive role, while avoiding large-scale anti-Maoist operations. However, coalition constraints and the government’s political dependence on Left parties limited its ability to adopt a more aggressive counter-Maoist posture.

In contrast, the UPA-II government, formed in 2009, could adopt a more assertive, security-driven strategy following the removal of coalition constraints. The approach evolved from a ‘development-first’ policy to a ‘clear–hold–develop’ strategy, which focused on regaining control of Maoist-affected areas in a phased manner. It also emphasised integrating security operations with developmental activities, ensuring that governance and welfare measures accompany military gains on the ground.[2] The clear–hold–develop strategy involves clearing the affected areas of rebels through counter-Maoist operations; second, holding the ground with a sustained security presence to prevent their return; and third, developing the area through infrastructure, welfare and other governance initiatives to win over the local population.

The government institutionalised coordination mechanisms by establishing Unified Commands in the worst-affected states of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha and West Bengal in 2010, bringing together senior officials from state police, central armed police forces, intelligence agencies, and the civil administration under a single structure to plan and coordinate anti-Maoist operations. It also strengthened the Multi-Agency Centre (MAC) by expanding its network of Subsidiary MACs (SMACs) in LWE-affected states, enabling real-time intelligence sharing among central and state agencies, including the CRPF, Intelligence Bureau and state police. These steps created a permanent, structured framework for joint planning, intelligence fusion and operational synchronisation between state and central forces in the fight against Maoist insurgency.

Additionally, the Union Government expanded the deployment of the CRPF battalion from 30 in 2004 to over 60 by 2009. This expansion in central assistance to states was to reinforce weak state police forces, provide specialised counter-insurgency capability, and maintain a sustained security presence in rugged terrain where state capacities were limited. At the same time, operational setbacks in the early 2000s exposed serious gaps. State police were often poorly trained and lacked guerrilla warfare tactics, and operated with inadequate weapons, communications and local intelligence; inter-agency information flow was fragmented; and ambushes revealed tactical and leadership gaps.

To address this, the government created Commando Battalion for Resolute Action (CoBRA) in 2008–09 as a specialised CRPF unit trained for jungle and guerrilla operations. The experience also highlighted the need to strengthen state forces and intelligence systems, leading to improved police training, better equipment, and the formation of local units such as the District Reserve Guards. Additionally, initiatives such as the Integrated Action Plan (IAP) and the Road Requirement Plan (RRP) were launched to improve basic infrastructure and service delivery in LWE-affected districts.

The IAP focused on quick-impact projects in health, education, drinking water, and livelihood generation to make the state’s presence visible in remote areas. The RRP, on the other hand, was formulated to connect isolated villages and security camps with district headquarters and market centres, thereby enabling access to essential services and faster troop movement. It was also utilised to establish security camps deep inside isolated regions. Under RRP-I, about 5,361 km of roads were sanctioned in 34 worst-affected districts across states like Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Bihar and Andhra Pradesh, of which over 5,000 km have been completed.[3] This has substantially reduced the physical and psychological isolation that had long sustained the Maoist movement.

Apart from these, land alienation and displacement were significant grievances among the tribal population. The widespread discontent stemmed from the colonial-era Land Acquisition Act of 1894, which allowed the government to acquire land with minimal compensation, limited transparency, and no provision for rehabilitation. This often led to forced displacement, loss of livelihoods and social unrest, particularly among tribal and rural communities in resource-rich areas. To address these historical injustices, the government enacted the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, to ensure just compensation, consent-based land acquisition, and comprehensive rehabilitation for displaced communities. These measures represented a synthesis of security assistance and development interventions aimed at addressing both the symptoms and the causes of extremism.

In 2009, the Union government urged states to intensify coordinated anti-Maoist operations across LWE-affected areas—especially in Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and West Bengal.[4] These targeted offensives led to the killing of senior Maoist leaders, including Azad in 2010 and Kishenji in 2011, disrupted key Maoist command structures, and significantly reduced the capability of Maoists to perpetrate violence. By 2013, Maoist-related incidents and fatalities had markedly declined (see Figure 1). However, the Maoists were not completely defeated. Sporadic but high-impact attacks—such as the Jhiram Ghati ambush in 2013 highlighted that the Maoists still possessed enough cadre and firepower to inflict damage on government personnel and property.

Overall, the UPA governments adopted a facilitative approach towards Left-Wing Extremism (LWE), placing the primary responsibility for operations on the states, as law and order is a state subject. The Centre’s role focused on funding, coordination and capacity-building, mainly through the Security Related Expenditure (SRE) and Modernisation of Police Forces (MPF) schemes. These funds enabled states such as Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Bihar and Andhra Pradesh to raise specialised Special Task Forces (STFs) and district-level counter-insurgency units, such as the SOG in Odisha, the Jharkhand Jaguar and the DRG in Chhattisgarh, thereby improving local combat capability and reducing dependence on central forces.

While the Centre directly intervened only in Chhattisgarh, where state capacity was weakest, it sought to strengthen inter-state coordination and intelligence sharing through the Multi-Agency Centre (MAC) and joint operations. On the perception front, the government focused on projecting the Maoists as anti-development, highlighting their attacks on civilians and infrastructure. Meanwhile, they promoted welfare and infrastructure schemes to win local confidence. Simultaneously, it maintained that dialogue would be possible only after Maoists abjured violence and accepted the Constitution, reflecting a firm stance that peace could not be pursued under the threat of arms.

Source: Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) and South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP), 2024

NDA Government’s Approach to LWE

The NDA government launched the National Policy and Action Plan (2015) to tackle LWE. While the new government’s strategy was essentially a continuation of the earlier multi-pronged approach to security measures, developmental projects, ensuring the rights and entitlements of local communities, and perception management, it ensured that the initiatives formulated thus far were effectively implemented. For example, the Modernisation of Police Forces (MPF) Scheme was streamlined in 2017 to address fragmented funding, overlapping sub-schemes and slow implementation. The revised framework consolidated funding under a single umbrella, prioritised capacity-building for state police, and emphasised technology-driven policing, including modern communication systems, forensic capabilities, and surveillance tools. Additionally, a dedicated Special Central Assistance (SCA) component was introduced to strengthen police infrastructure and operations in LWE-affected districts.[5] The 2017 reform thus marked a significant policy shift towards a more integrated and security-focused modernisation of India’s policing system.[6]

Meanwhile, the Maoists continued to carry out sporadic but high-impact attacks, such as the 2017 Sukma ambush in which 25 CRPF personnel were killed. The incident exposed serious deficiencies in inter-agency coordination and in real-time intelligence sharing among security forces operating in LWE-affected areas. To address these shortcomings, the Union Ministry of Home Affairs launched the SAMADHAN[7] doctrine in 2017 as a comprehensive counter-LWE strategy. It serves as a multi-dimensional framework that integrates intelligence, operations, capacity-building and financial disruption into a single, data-driven doctrine. SAMADHAN institutionalised the government’s counter-insurgency approach by combining security operations, intelligence efficiency, and financial containment and became the central guiding framework for all subsequent LWE policies and security operations.

Primary coordinated operations such as Operation Prahar (2017), Operation Kagar (2024) and Operation Black Forest (2025) significantly degraded the CPI (Maoist) operational network and leadership. These efforts led to a steady reduction in Maoist incidents (by nearly 70 per cent as compared to 2013, a sharp fall in affected districts (from 126 in 2013 to 11 by October 2025), and the restoration of administrative control in formally isolated regions. The intensified operations can be attributed to political will, the convergence of strategic objectives at the Centre and state levels, improved intelligence and inter-state coordination, the expansion of security presence along with road and telecom connectivity, effective utilisation of localised forces (DRG, C60, etc.), and community engagement.

One of the significant factors behind the weakening of Left-Wing Extremism has been the Union Government’s success in targeting the Maoists’ financial network. For decades, the CPI (Maoist) sustained its operations through a parallel taxation system that extracted ‘levy’ or ‘revolutionary tax’ (Jungle tax) from contractors, corporate houses, mining operators, tendu-leaf traders and infrastructure projects in remote Maoist-affected areas. Besides these, drug trafficking is another vital source of Maoist finance.[8] The National Investigation Agency (NIA), Enforcement Directorate (ED), and state police have jointly investigated Maoist-linked shell companies, NGOs and sympathisers who channelled funds and laundered the proceeds from their operations.[9] The freezing of assets, cancellation of shady mining and tendu-leaf contracts,[10] and stricter cash-flow regulation in LWE zones have curtailed the insurgents’ economic base.[11] Demonetisation in 2016 and increased digitalisation of government payments further constrained the cash economy that sustained the Maoists.[12]

Challenges

Despite significant progress in curbing Maoist violence, the campaign against LWE continues to face enduring structural, institutional and governance challenges. For instance, the legislative measures such as the PESA (1996), the FRA (2006), and the Land Acquisition Act (2013), though conceptually sound, suffer from implementation gaps, bureaucratic inertia and weak local capacities.[13] As a result, large sections of tribal communities are unable to exercise whole land and forest rights, leading to a sense of alienation and distrust towards the state, making them potential cadres for the Maoist movement.

On the security front, the government needs to be cautious about the post-operation consolidation of the secured areas. In the past, the absence of sustained governance and developmental consolidation in newly secured areas left room for Maoist regrouping. Also, reports of police excesses have strained community relations and, consequently, weakened the flow of local intelligence. Moreover, while the MPF Scheme has significantly strengthened the operational and technological capacities of state police, its impact has been uneven across states. Gaps in fund utilisation, training standards and intelligence integration continue to limit the complete consolidation of security gains in LWE-affected regions.[14]

While the governments have succeeded in reducing Maoist violence by over 80 per cent and regained administrative control in most affected districts, lasting peace depends on governance reforms and social legitimacy. The eradication of LWE by 2026 appears achievable, as there has been substantial attrition in the top Maoist leaders. Due to enhanced intelligence and intensified security operations, key Maoist leaders have either been killed[15] or surrendered. The CPI (Maoist) has suffered a sharp organisational decline, with its Politburo reduced from 14 members in 2009 to just 3–4 active leaders, and its Central Committee shrinking from over 40 in 2010 to around 10–14 members. This contraction reflects the impact of sustained anti-Maoist operations by the security forces and internal disunity among CPI (M), severely weakening the group’s leadership and coordination.

Further, the deaths, arrests and surrenders of key leaders have fractured the organisation, deepening internal divisions and prompting several senior cadres to abandon the movement. Government efforts that combine counter-insurgency operations with targeted development programmes have significantly reduced the grievances that once sustained the insurgency. However, the Maoists continue to exert limited influence in the dense forests of Dandakaranya, where unresolved land rights and tribal autonomy issues persist.

Way Forward

To meet the target of eliminating LWE by March 2026, the focus now lies on strengthening and sustaining the progress already made. The real challenge is not designing new policies but ensuring that state governments effectively implement existing ones. Continued coordination under frameworks such as the National Policy and Action Plan and the SAMADHAN Doctrine remains vital to maintaining security pressure on the remaining Maoist strongholds. Equally important is improving local policing, intelligence networks and administrative presence in recovered areas, coupled with timely development and welfare delivery. Effective enforcement of laws protecting tribal rights and livelihoods, along with firm action against Maoist front organisations, will be essential to prevent the movement’s resurgence and secure lasting peace.

However, law enforcement alone cannot guarantee stability; development must reach the remotest tribal areas through better infrastructure, education, healthcare and livelihood opportunities. Empowering local communities through participatory governance and ensuring transparent implementation of welfare schemes can help rebuild trust in the state. Equally important is addressing the ideological dimension of LWE- by making Maoist narratives less appealing to the youth through political inclusion, awareness and strengthening faith in India’s democratic and constitutional framework. Only a balanced approach combining security, development and democratic engagement can ensure enduring peace in the affected regions.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

[2] “Naxal Problem Needs a Holistic Approch”, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 22 July 2009.

[3] Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 2041, answered on 15 March 2022.

[4] Operation Anaconda (Jharkhand), Operation Lalgarh (West Bengal) and Operation Green Hunt.

[5] “Guidelines for the Scheme of ‘Special Central Assistance (SCA)’ for 35 Most LWE Affected Districts”, Transformation of Aspirational Districts Programme.

[6] “Union Home Minister Chairs the Review Meeting of LWE-affected States”, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 8 May 2017.

[7] The term SAMADHAN is an acronym that stands for Smart leadership, Aggressive strategy, Motivation and training, Actionable intelligence, Dashboard-based KPIs and KPAs, Harnessing technology, Action plan for each theatre, and No access to financing.

[8] Om Prakash, “Funding Pattern in the Naxal Movement in Contemporary India”, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 76, 2015, pp. 900–907.

[9] “NIA Chargesheets Four More for Funding Maoist Activities in Chhattisgarh”, The New Indian Express, 1 October 2025.

[10] “Chhattisgarh: Five Held for Extorting from Tendu Leaf Contractors to Finance Naxalites”, The Indian Express, 10 August 2024.

[11] “Commandos Choke Maoist’s Rs 200 crore Tendu Terror Fund with Three Encounters in 72 hours”, The Times of India, 7 June 2024.

[12] “Demonetisation Effect: Funds Tap Turns Dry for Terror and Maoist Groups”, The Economic Times, 13 July 2018.

[13] “Report of the Working Group on Forest Rights and Community Forest Rights”, Promoting Community Forest Rights in Central India, p. 11.

[14] “Modernisation of Police Forces”, The PRS Blog, 3 October 2017.

[15] “Union Home Minister and Minister of Cooperation Shri Amit Shah says, in a landmark achievement in the battle to eliminate Naxalism, security forces have neutralized 27 dreaded Maoists in an operation in Narayanpur, Chhattisgarh”, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 21 May 2025.