India’s Forgotten Role in the Korean Armistice

- December 09, 2025 |

- IDSA Comments

The Genesis of Division

The tragedy of the Korean Peninsula began with a simple cartographic decision. The 38th parallel was not a cultural or political boundary,[1] it was a hastily drawn, temporary military line at the end of World War II by US planners, intended solely to accept the surrender of Japanese forces (Soviet forces accepting surrender north of the line, US forces accepting surrender south of the line). This line, meant to keep Soviet influence out of the key strategic prize of Japan, hardened into a political division.

A critical miscalculation in Washington set the stage for invasion. In January 1950, US Secretary of State Dean Acheson delivered his defining “defensive perimeter”[2] speech at the National Press Club. This statement, which excluded South Korea from the explicit American defence line, was widely interpreted by critics as giving North Korean leader Kim Il Sung the ‘green light’ to pursue forcible reunification. Though Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had previously refused to sanction the invasion, fearing US intervention, this perceived American withdrawal emboldened Kim to press again, successfully securing Stalin’s reluctant endorsement by April 1950.

Even before the war, India, through K.P.S. Menon, the Chairman of the UN Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK), desperately sought a unified solution, once stating, “What God hath joined together, let no man put asunder”. But unity was impossible, and separate elections proceeded, cementing the split. When North Korea invaded on 25 June 1950, India swiftly condemned the aggression and supported the initial UN Security Council resolution calling for withdrawal.

Yet, demonstrating its “principled neutrality”, India opted not to send combat troops. Instead, it made a strategic humanitarian commitment: deploying the 60th Para Field Ambulance.[3] This was no static hospital unit, but an airborne surgical team led by India’s first paratrooper, Lt Col A.G. Rangaraj, that flew with offensive operations, earning numerous gallantry awards and providing critical, indiscriminate care.

The Constraining Role

The war’s trajectory saw UN forces, led by General Douglas MacArthur, driven back to the Pusan Perimeter, only to be dramatically reversed by the Incheon Landing and a surge northward to the Yalu River. It was here that India’s diplomatic machinery became indispensable. K.M. Panikkar, India’s Ambassador to Peking (Beijing), acted as a crucial communication bridge. He relayed a chilling warning through Prime Minister Nehru: if UN forces crossed the 38th parallel and approached the Yalu River, China would intervene with armed force, viewing it as aggression. This advice went unheeded.

China, a nascent republic just unified, entered the fray, initiating what remains, to this day, the first and only direct military confrontation between China and the United States. The war devolved into a grinding back-and-forth until President Harry S. Truman famously sacked General MacArthur in April 1951. Truman decided that MacArthur had repeatedly overstepped his authority, defied direct orders, and desired to escalate the conflict, including the potential use of nuclear weapons.

The Blueprint for Peace

The war eventually stalled over a single, intractable issue: the forced versus voluntary repatriation of prisoners of war. Negotiations remained deadlocked until the death of Joseph Stalin in March 1953 helped spur the Soviet side towards a quick end to hostilities. India, through the efforts of V.K. Krishna Menon, played the defining role. Menon relentlessly lobbied the Arab-Asian, Commonwealth, Chinese, US and UK blocs, crafting the Indian Resolution of 1952. This resolution broke the stalemate by establishing the principle of voluntary repatriation under the neutral custody of an independent commission.

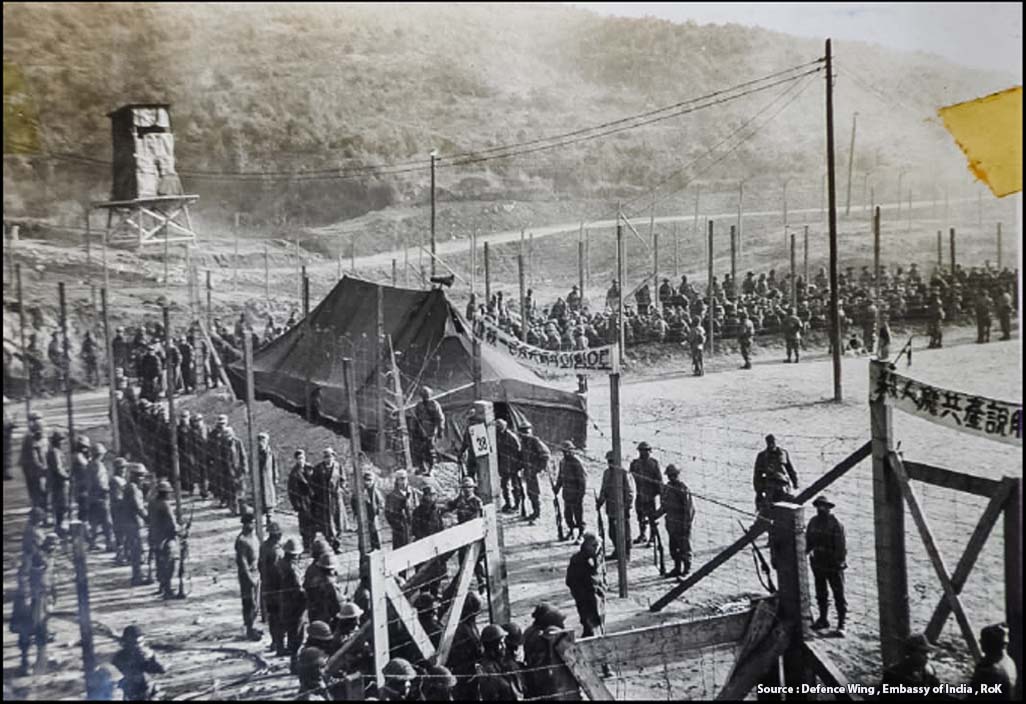

To implement this principle, India took the challenging step of deploying the Custodian Force India (CFI), drawn from the 190 Brigade, to handle thousands of non-repatriated prisoners physically. India chaired the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission (NNRC), which was structured as a precarious tightrope walk: two members from the Western bloc (Sweden and Switzerland) and two from the Communist bloc (Poland and Czechoslovakia), leaving India as the sole arbiter.

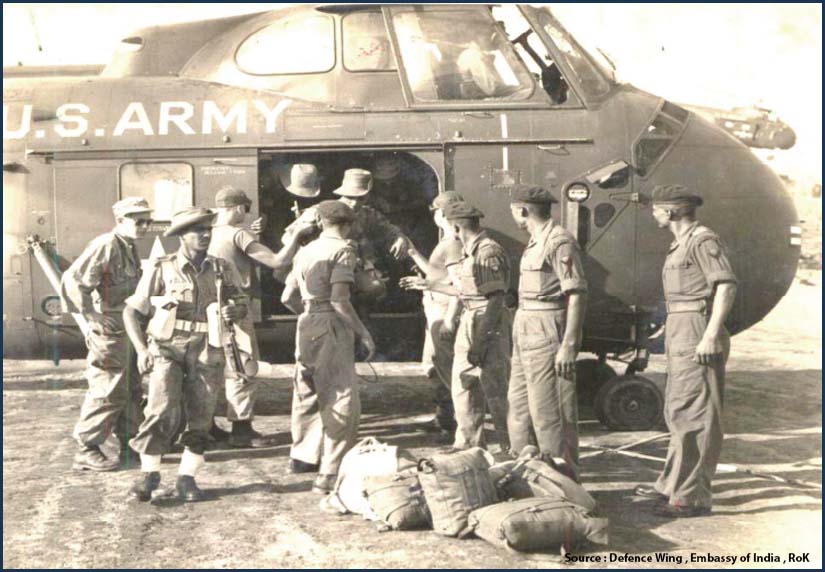

This mission was instantly fraught with political peril. South Korean President Syngman Rhee, intensely distrustful of India’s neutrality, refused to allow the Indian ships to land.[4] This hostility necessitated the extraordinary operation where the US was forced to arrange for the helicopter transport of the entire CFI contingent (a force of approximately 6,000 troops) directly from the decks of the ships to the neutral area in Panmunjom.

Source: Defence Wing, Embassy of India, RoK

The CFI’s professionalism in this politically insensitive climate was its greatest triumph. When Chinese prisoners staged a riot and detained Major Grewal of 6 JAT, Major General S.P.P. Thorat, the CFI Commander, personally intervened unarmed, walking into the unruly compound to secure the officer’s release and defuse the crisis without firing a shot—an act of restraint that contrasted starkly with the potential for armed intervention. This disciplined action, alongside the leadership of NNRC Chairman Lieutenant General K.S. Thimayya, earned the appreciation of leaders, including US President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

On 20 February 1954, The New York Times reported that Eisenhower praised the Indian forces, in a personal message to Prime Minister Nehru. Eisenhower stated, “No military unit in recent years has undertaken a more delicate and demanding peacetime mission”. He specifically commended the “exemplary tact, fairness, and firmness” of Lt Gen K.S. Thimayya and Maj Gen S.P.P. Thorat, noting that their leadership did much to alleviate the fears of the prisoners.[5]

When the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission (NNRC) dissolved in February 1954, the Custodian Force India (CFI) returned to India with 88 former prisoners of war (74 North Koreans, 12 Chinese, and 2 South Koreans) who had refused repatriation to their homelands but had not yet found asylum in neutral nations. These men were brought to New Delhi and housed at the Red Fort.[6]

Source: Defence Wing, Embassy of India, RoK

A Legacy of Division and Strategic Partnership

The legacy of Korea stands unique. While North and South Vietnam unified under communism, North and South Yemen merged, and Germany was reunified, Korea remains the only major Cold War division that persists today. In the immediate aftermath, South Korea’s government continued to distrust India, but relations began to mend slowly under the Park Chung-hee government. While initially wary of India’s Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) stance, President Park Chung-hee admired India’s centralised economic planning. Under his leadership, relations were upgraded to full diplomatic status in December 1973. This marked the beginning of separating economic engagement from Cold War ideology, laying the groundwork for the current Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA).

Today, the relationship has moved towards a strategic partnership, underpinned by personal diplomatic connections: former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon deliberately chose New Delhi for his first overseas posting, describing it as an “important and adventurous posting”[7]. Furthermore, the current Republic of Korea Foreign Minister, Cho Tae-yul, is a former Ambassador to India, having written a book documenting his tenure.[8]

India’s Korean War experience—from the first humanitarian mission to the final, tense task of separating prisoners—validated its non-aligned foreign policy and established a global tradition of peacekeeping. It proved that in an ideologically polarised world, active neutrality was not a compromise, but the only path to a pragmatic and workable peace.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

[1]The 38th Parallel was chosen on the night of 10 August 1945, by two young US Colonels, Dean Rusk (later Secretary of State) and Charles Bonesteel. Working with a National Geographic map and pressed for time, they selected the line because it placed the capital, Seoul, in the American zone. Rusk later admitted “neither of us was a Korea expert”, highlighting the arbitrary nature of a decision that has divided a people for over seven decades. Dean Rusk, as told to Richard Rusk, As I Saw It, W. W. Norton & Company, New York, 1990. Also see “How 38th Parallel Became Demarcation Line Between South and North Korea in 1945?”.

[2] Dean Acheson’s speech on 12 January 1950, defined the US defensive perimeter as running from the Aleutians to Japan, the Ryukyus and the Philippines, notably omitting Korea. This is frequently cited by historians as the signal that inadvertently encouraged North Korean aggression. Dean G. Acheson, “Crisis in Asia—An Examination of U.S. Policy”, Speech, National Press Club, Washington, D.C., 12 January 1950, Department of State Bulletin 22, no. 551, 23 January 1950, pp. 111–118, accessed via “The World and Japan” Database, National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS).

[3] The 60th Para Field Ambulance became independent India’s first overseas mission and has been till date the longest serving one. The unit, commanded by Lt Col A.G. Rangaraj, served for three and a half years (November 1950–February 1954), treating over 200,000 casualties. They were awarded two Maha Vir Chakras, and six Vir Chakras. D.P.K. Pillay, “Forgotten Tales of Courage and Valour: The Bucket Brigade”, The Economic Times, 9 July 2020. For further reading, may please see Satish Nambiar, For the Honour of India: A History of Indian Peacekeeping, Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research, United Service Institution of India, New Delhi, 2009.

[4] President Syngman Rhee, labelling the Indians as “pro-communist” for their neutral stance, threatened to arrest Indian troops if they set foot on South Korean soil. Consequently, the US Army had to launch Operation Cudgel to helicopter lift the Indian Custodian Force (CFI) who were transported by US helicopters from the decks of their transport ships directly to the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), bypassing South Korean territory entirely to avoid diplomatic incidents. See Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952–1954, Korea, Vol. XV, Part 2, Document 651 (Letter from Rhee to Walter S. Robertson, 1 July 1953). Regarding the airlift logistics, see Lee Ballenger, The Final Crucible: U.S. Marines in Korea, Vol. 2, 1953, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2002, pp. 168–170.

[5] “Eisenhower Lauds India’s Korea Force”, The New York Times, 20 February 1954.

[6] Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru personally met this group, reinforcing India’s commitment to their welfare. They remained under India’s care until they could be resettled in neutral countries such as Brazil, Argentina and Mexico, or chose to remain in India. Lok Sabha Debates (Parliament of India), Part I: Questions and Answers, Vol. V, No. 13 (August 10, 1955), Starred Question No. 627 regarding “Korean Prisoners of War”. May also see, Robert Barnes, “Between the Blocs: India, the United Nations, and Ending the Korean War”, The Journal of Korean Studies, Vol. 18, No. 2, Fall 2013, pp. 263–286. Barnes documents how the 88 ex-prisoners were brought to India after the NNRC dissolved and remained there until most were resettled in South American nations like Brazil and Argentina.

[7] Ban Ki-moon, “What I Gained from Choosing the Rocky Road”, LinkedIn (Pulse), 2 March 2016. In this reflection, the former UN Secretary-General explains that he “deliberately chose what I saw as an important and adventurous posting, in New Delhi” for his first overseas assignment. This sentiment was personally reiterated to the author during a meeting with Mr Ban Ki-moon in Seoul in July 2025, where he reflected on how his tenure in India (1972–1975) shaped his diplomatic worldview.

[8] Cho Hyun, Hanguk daesa-ui Indo ripoteu [Korean Ambassador’s Report on India] (Seoul: Maekyung 2020). In this memoir, Cho Hyun, who served as the South Korean Ambassador to India from 2015 to 2018, documents his diplomatic experiences and offers a strategic vision for the India–Korea partnership.