You are here

| Title | Date | Date Unique | Author | Body | Research Area | Topics | Thumb | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iran Delinks Regional and Nuclear Diplomacy | July 29, 2022 | Deepika Saraswat |

When European Union-mediated negotiations between Iran and the United States in Doha ended on 29 June 2022 without breaking the nearly four months’ long stalemate in nuclear talks, Iran and its Western interlocutors articulated very divergent views on the prospects of reviving the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). In a telephone call with his Qatari counterpart Mohammed bin Abdulrahman bin Jassim Al Thani, Iran’s Foreign Minister Hossein Abdollahian noted his positive assessment of talks and underlined that Iran was determined to continue the negotiations till a good, strong and lasting agreement is reached. He added that if the US is realistic, an agreement will be “achievable”.1 Prolonging the Nuclear TalksThe Raisi administration delayed resumption of nuclear talks for four months after assuming office in August last year. By sticking to its key demands on guarantees and comprehensive sanctions relief, Iran aims to underline that Trump-era ‘maximum pressure’ campaign, which has continued under the Biden administration, will not lead Tehran to compromise. Since the new Iranian team led by Ali Bagheri Kani, Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister, entered nuclear negotiations in November last year, its negotiating approach has been marked by brinkmanship. Officials in the conservative Raisi administration contrast this approach with the ‘passive diplomacy’ attributed to moderates and reformists, who pursued policy of dialogue and compromise while engaging with the West on Iran’s nuclear file. Regional Diplomacy delinked from Nuclear DiplomacyIran’s dialogue with Saudi Arabia, which was initiated in parallel with the nuclear talks under the Rouhani administration, has seen progress under Raisi, suggesting dynamics at play independent of the state of the nuclear talks. Iraq has mediated five rounds of Iran–Saudi dialogue at the level of security elites and focussing on ceasefire in Yemen, among other issues. In July, Iran confirmed that the dialogue will now move to the political level between foreign ministers of the two countries.6 ConclusionIran’s influence in key conflict theatres in Yemen and Syria, its proven capabilities for raising collective insecurity for the region and deepening security ties with Russia, have given it the upper hand in diplomacy with its regional rivals. Over more than a year of nuclear negotiations have shown that instead of banking on a successful outcome in Vienna, Iran, especially under Raisi, is focussing its diplomatic energies on advancing its ‘neighbourhood policy’ and long-term cooperation with China and Russia. These policies are not only in line with the Supreme Leader Khamenei’s vision of ‘resistance economy’ aimed at minimising the economic impact of US sanctions, but also aim to situate Iran favourably in the emerging alternative Eurasian order. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Eurasia & West Asia | Nuclear Cooperation, Iran | system/files/thumb_image/2015/iran-nuclear-t_0.jpg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Central Asia: Key to Engaging China and Russia | Deepak Kumar |

About the AuthorColonel Deepak Kumar is a serving officer of the Indian Army. A graduate of Long Gunnery and Defence Services Staff College Courses, he commanded a Field Artillery Regiment and has been an Instructor in the Indian Army School of Artillery, Devlali. The officer has taken part in Operation Vijay, Operation Meghdoot, Operation Parakram and Operation Rakshak. He has been awarded Army Commander’s and Chief of Army Staff Commendation Cards. He has written extensively on international conflicts, strategic issue and military history. |

system/files/thumb_image/2015/monograph.JPG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National Hospital Ship and India’s Maritime Security Strategy | July 29, 2022 | R. Vignesh |

In May 2022, a Request for Information (RFI) was issued by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) for the construction of a National Hospital Ship (NHS) for the Indian Navy.1 The RFI has indicated that the navy seeks the construction of a task-specific ship that is capable of providing mobile and comprehensive medical care to patients on the high seas. The acquisition of such a ship for the Indian Navy’s fleet is timely, taking into consideration two important factors. First, the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is increasingly becoming susceptible to recurrent natural disasters owing to the effects of climate change. Second, India is currently engaged in making efforts for the reorientation of its image from being perceived regionally as a ‘Net Security Provider’ to that of a ‘Preferred Security Partner’.2 Hospital ships play a critical role in supplementing a navy’s combat potential, enhancing its soft power capability and augmenting its ability to be the first responder to humanitarian crises. Strategic and Tactical Naval AssetMajor naval powers across the world possess hospital ships in their fleets. The 1949 Geneva Conventions prohibits belligerent parties from attacking vessels that are designated as hospital ships. Article 22 in the Third Chapter of the Second Geneva Conventions 1949 defines military hospital ships as vessels built or equipped by navies solely for the purpose of treating the wounded and transporting them.3 Supplement Combat CapabilitySupporting combat operations has always been the traditional role of hospital ships of navies the world over. Hospital ships have played a pivotal role in supporting the US Navy’s combat operations since the American Civil War in the 19th century.4 These ships are forward-deployed by navies to provide rapid and flexible medical support to injured combatants and civilians. During the 2003 US Invasion of Iraq, the US Navy forward-deployed its 1,000-bed hospital ship, USNS Comfort, to the Persian Gulf. As the invasion progressed, hundreds of US military personnel received immediate medical treatment on board the USNS Comfort for combat-related injuries. After the combat operations, the ship provided trauma care to some Iraqi civilians injured during the invasion.5 Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster ReliefOver 40 per cent of the world’s population resides within 100 kilometres of the coast. The heavy population density and economic activity in the littoral regions puts tremendous pressure on the coastal ecosystem.7 The effects of climate change have resulted in the growing recurrences of cyclones, droughts, earthquakes, tsunamis, floods and tidal surges. This creates a domino effect on poverty, famine and societal imbalances in the world’s coastal zones. As a result, Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) and Non-combatant Evacuation Operations (NEO) have become key maritime security challenges for modern navies.8 Projecting Soft PowerJoseph S. Nye defined soft power as the ability to obtain preferred outcomes through appeal and attractions.9 To this end, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has extensively utilised its first hospital ship, Dhaishan Dao (also known as Peace Ark), for projecting Chinese soft power across the IOR and beyond. Since 2010, the ship has regularly embarked on voyages to South Asia, Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America. During its port visits to several developing nations, the Peace Ark engages in conducting altruistic and philanthropic activities among the local populace. A notable example of this was during the Peace Ark’s first port visit to Chittagong in 2010, where the crew of the ship saved a local Bangladeshi woman with complications arising from pregnancy. This is an illustration of how these vessels can play an important role in building favourable public opinion at the grassroots level overseas, even during non-crisis times.10 Importance of a Hospital Ship for the Indian NavyIndia has always been a de facto first responder to crises in the IOR owing to its geographical position and military prowess. However, the IOR and its littorals have become far more vulnerable to natural disasters and other calamities than any other maritime region. The 2004 Tsunami underscored the necessity for naval assets like hospital ships to spearhead large-scale HADR operations. Robert Kaplan opines that in the face of receding American naval presence in the region, the US can no longer be the prime deliverer of disaster assistance in the IOR.12 In such a scenario, naval capabilities of India, China, Australia, Japan and South Korea must be augmented to respond to future emergencies.13 ConclusionThe significance of hospital ships in navies has acquired greater strategic significance owing to changing maritime security dimensions. The threat to the coastal population from natural disasters, pandemics and other man-made calamities has increased substantially. Recent developments in Europe and the Indo-Pacific have also underscored the resurgence of great-power competition and the risk of state-on-state confrontation. In this context, the relevance of hospital ships to modern navies has risen considering their potential as combat enablers, first responders and symbols of the state’s soft power. As an emerging blue water navy, the national hospital ship provides great value addition to India’s maritime capability by serving as the flagship for projecting Indian soft power and as an auxiliary ship for augmenting Indian hard power across the IOR. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Military Affairs | Indian Navy, Maritime Security | system/files/thumb_image/2015/hospital-ship-t.jpg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Increased Drug Trade in Golden Triangle: Security Implications | July 28, 2022 | Akash Sahu |

The Laotian police busted about 36.5 million methamphetamine pills in north-western Bokeo province in January 2022. 1 Earlier in October 2021, they found 55.6 million pills from the same area in addition to more than 1.5 tonnes of crystal meth or “ice”.2 These illicit substances are produced in the Shan state of Myanmar, and transported to Thailand via Laos. In the aftermath of the coup in Myanmar in February 2021, reports note the production has shot up exponentially, and record amounts have been seized.3 Such unregulated production and trafficking of drugs poses multifaceted threats, including those related to law and order, social problems associated with increased addiction, and transnational crimes with illicit money fuelling insurgent activities in the region and beyond. Shan State and the Golden TriangleThe Shan state of Myanmar is the largest producer of illegal drugs within the infamous Golden Triangle—a tri-junction at the Myanmar, Laos and Thailand borders. Before Afghan drug produce flooded the international market in the 1990s, the Golden Triangle was the largest producer of heroin in the world. Since the 2010s, however, production of the more potent and profitable methamphetamine has made the region, the world’s largest producer and exporter of meth.4 Implications for India’s NeighbourhoodIndia’s long, porous land border with Myanmar provides safe haven for entry of drugs such as yaba and heroin. Consignments of heroin seized in Indian cities like Guwahati and Dimapur have originated from the Golden Triangle. Myanmar’s heroin and meth enter India at two points, Moreh in Manipur and Champai in Mizoram.12 Precursor chemicals, like ephedrine, acetic anhydride and pseudo ephedrine, are sourced from places in South India like Chennai and transported to Kolkata and Guwahati via Delhi before being smuggled across the border to Myanmar, highlighting domestic security gaps. Measures by Indian GovernmentSome recent measures by the Indian government to control drug trafficking include setting up of the Narco Coordination Centre in 2016, a mechanism under the NCB which was restructured in 2019 into a four-tier district-level scheme. An e-portal, Seizure Information Management System, was also launched in 2019 under the Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, for better coordination of all drug law enforcement agencies.23 Multilateral EffortsIndia’s NCB works with several international agencies like SAARC Drug Offences Monitoring Desk, BRICS, Colombo Plan Drug Advisory Program, ASEAN Senior Officials on Drug Matters, BIMSTEC, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), and International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), among others, to combat the illicit trade of drugs. Given that Myanmar is the most significant site for drug production, more focussed efforts at engaging Naypyitaw over the issue may be useful from an Indian perspective. India, Bangladesh, Thailand and Myanmar are all members of BIMSTEC, which makes it the suitable platform to coordinate activities at countering this menace. ConclusionTrafficking of illicit drugs is a global problem and places such as the Golden Triangle are its hotspots. The drug money is used to finance criminal activities and even terrorism. Multilateral cooperation of South and Southeast Asian countries in the banking sector for tracing of illicit money from drug trade can be very helpful in dealing with the trans-national nature of this menace. One such international joint operation in 2021 led by the US Department of Justice and Europol successfully led to the arrest of 150 drug peddlers (in US and European countries like France, Germany and Italy, and even in Australia) who were using dark web to sell drugs. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

South East Asia and Oceania | Drug Trafficking, Myanmar, Thailand | system/files/thumb_image/2015/myanmar-drug-t.jpg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| US and EU Sanctions on Russian Defence Industry | July 25, 2022 | S. Samuel C. Rajiv |

The Russian Federation is one of the major global arms exporters. The top five importers of Russian arms during 2010–21 were India, China, Algeria, Vietnam and Egypt. Russia’s share of global arms trade, however, has gradually decreased from 26 per cent in 2011–15 to 19 per cent in 2017–21.1 In the last five years (2017–21), while Russian arms made up more than 80 per cent of China’s and Algeria’s arms imports, they accounted for 56 per cent of Vietnam’s, 46 per cent of India’s and 41 per cent of Egypt’s arms imports. Due to Russia’s military actions in Ukraine, since 2014, Russia has been subjected to sanctions measures by the United States (US), European Union (EU) and other countries. In the wake of its February 2022 military action in Ukraine, these sanctions have been further strengthened. The sanctions have targeted key Russian arms producing firms, their design bureaus, export organisations and their leadership, as well as the export and import of dual-use products. This Issue Brief examines the different US and EU sanctions on the Russian defence industry, and the implications they have had for Russian arms importing countries, like Turkey and Indonesia. Given that India is one of the largest importers of Russian arms, it has been impacted by such sanctions. EU SanctionsAs part of EU sanctions, more than a thousand individuals and nearly 100 entities are subject to travel bans and asset freezes. Six ‘packages’ of sanctions have been imposed beginning from 23 February till 3 June, with sanctions targeting 70 per cent of Russia’s banking system (as per the EU’s contention), closed EU airspace and ports to Russian aircraft and vessels and imposed import and export restrictions on items like Russian steel (with effect from August 2022), coal, crude oil, among others.2 As regards defence and dual-use sectors, business transactions with key companies in the aviation, shipbuilding and machine-building sectors are threatened to be sanctioned, while export restrictions on dual-use goods and technology that could ‘contribute to the technological advancement of Russia’s defence and security sector’ were tightened.3 While the prohibition on dual-use goods has been in place for military end-users, it was extended to civilian end-users too from February 2022. Analysts note that restrictions on sourcing critical components like semi-conductors, machining equipment, among others, will negatively impact the ability of Russia’s defence industrial enterprise. Micro-electronics and high-end machining equipment were described as the ‘achilles heel’ of the Russian defence industry, way back in 2015, by Deputy Prime Minister Dmitri Rogozin.4 Prior to the latest round of sanctions, the EU arms export and import ban has been in place since July 2014. The EU, in Council Decision 2014/512/CFSP, banned the export and import of arms, including sale, supply or transfer of weapons, ammunition, military vehicles, or technical and financial assistance for military activities.5 More than EUR 900 million of defence trade took place between EU states and Russia, however, in the period 2010–20, with significant portion of it contributed by countries like France, Germany and Italy.6 Reports note that German engine parts and global positioning systems (GPS) have been found in Russian drones shot down in Ukraine. Italy has exported military trucks and semi-automatic weapons and ammunition, while infra-red systems for fighter jets and thermal imaging equipment for tanks, among other equipment, have been exported by France.7 Russian arms have also been exported to EU member states—to Cyprus, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia, in the past decade, though the majority of these exports have happened prior to 2012. To be sure, the 2014 ban did not prohibit servicing of spares, among others, for contracts entered into prior to August 2014. EU sanctions measures are also not applicable for equipment meant for civilian nuclear use, or for transactions involving companies jointly or solely owned by EU entities. There has been a reduction, though, in arms export licenses from EU states to Russia, reducing from 940 in 2013 to 86 in 2020 (see Tables 1 and 2).8 EU states insist, therefore, that they have been strictly following the sanctions measures. The EU, in April 2022, also removed this exemption relating to servicing of arms equipment brought prior to August 2014.9 Table 1. Top 10 EU Arms Exporters to Russia (2010–2020)

Table 2. Arms Exports Licenses by EU States to Russia 2010–20

US SanctionsThe Obama administration passed Executive Order (EO) 13661 and EO 13662 in March 2014 blocking the ‘property or interests in property of persons operating in the arms and related material sectors of the Russian Federation’.10 These two authorities were later codified by the Countering American Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA). In July 2014, the US Treasury designated and blocked the assets of Russian military enterprises like Almaz-Antey, Federal State Unitary Enterprise State Research and Production Enterprise Bazalt, JSC Concern Sozvezdie, JSC MIC NPO Mashinostroyenia, Kalashnikov Concern, KBP Instrument Design Bureau, Radio-Electronic Technologies, and Uralvagonzavod, under EO 13661.11 The Ukraine Freedom Support of December 2014 imposed sanctions on the Russian arms export organisation, Rosoboronexport and threatened sanctions on ‘any person for knowingly facilitating a significant financial transaction with any Russian producers, transferors or brokers of defence articles’. The Act had an in-built waiver for not imposing these sanctions for national security reasons.12 CAATSA, meanwhile, was passed in 2017 as a measure to punish Iran, Russia and North Korea for their alleged malicious activities. Russian ‘malafide’ actions that were flagged included its invasion of Georgia (2008), Ukraine (2014) and Crimea (2014) and its alleged involvement in the 2016 US Presidential elections. Section 231 of CAATSA prescribed ‘sanctions for engaging in “significant” transactions with defence and intelligence sectors of Russia’.13 These sanctions included restrictions on accessing US EXIM Bank loans, denial of export sanctions, prohibition of loans from US financial institutions totaling more than US$ 10 million, opposing loans from international financial institutions, and sanctions on principal executive officers of entities who indulge in such ‘significant transactions’. In September 2017, the US President delegated the authority to implement Section 231 to the US Secretary of State, in consultation with US Treasury Secretary. Turkey has been at the receiving end of US sanctions pressure on account of its US$ 2.5 billion purchase of the S-400 system, announced in December 2017. Negotiations for the system had commenced in June 2016, after the deal for a similar Chinese system was cancelled in November 2015, over contentions regarding transfer of technology (ToT) issues.14 The Chinese system was chosen in September 2013. After the Chinese deal was cancelled, negotiations were also held with US companies like Raytheon and Lockheed Martin—makers of the Patriot system—but disagreement over ToT stymied the deal. Turkey began constructing S-400 base in September 2018. The US removed Turkey from the F-35 programme in June 2019. Turkey was to get nearly 100 F-35 jets and Turkish companies were making F-35 centre fuselages and cockpit displays. Reports noted that approximately 7 per cent of the jet’s parts were being made in Turkey.15 While the F-35 removal was not prescribed under CAATSA sanctions, the US took the decision after Turkey sent personnel to Russia for training on the S-400 system. The US insisted that the S-400 procurement would lead to Turkish strategic and economic overdependence on Russia. The White House asserted that the F-35 cannot co-exist with a Russian intelligence collection programme (S-400) and that its acquisition undermines the commitments of NATO allies to move away from Russian systems.16 In December 2020, Section 231 CAATSA sanctions were finally imposed on Turkey’s arms procurement agency (SSB), including asset freezes and visa restrictions on its president and other officers. As for recent developments on Turkey–US defence ties, the US State Department, in letter to Congress on Turkey’s request for F-16 fighters, stated that ‘compelling long-term NATO alliance unity and capability interests, as well as US national security, economic and commercial interests are supported by appropriate US defense trade ties with Turkey’ and noted that Turkey had already paid a ‘significant price’ on account of its removal from the F-35 programme and the CAATSA sanctions.17 Apart from Turkey, other countries that have been sanctioned by the US over their arms relationship with Russia include China. CAATSA sanctions were imposed on the Chinese arms procurement agency, EDD, and its director, in September 2018. The Chinese purchase of the Su-35 fighter jet in 2017 and the S-400 system in 2018 were deemed as ‘significant’ transactions with the Russian defence industry.18 Indonesia in December 2021 also backed out of deals to buy 11 Su-35 jets for more than US$ 1 billion.19 Reports in 2019 had noted that Morocco was reconsidering an option to buy the S-400, in view of the threat of US sanctions. In January 2021, the US approved the sale of the Patriot air defence system to Morocco.20 Consequences for IndiaUS and EU sanctions measures have added pressure to India’s strategic options. India is one of the largest importers of Russian arms, accounting for nearly 34 per cent of Russia’s exports, during 2010–21, followed by China, at 13.5 per cent.21 The head of Rostec, the Russian arms conglomerate, in August 2021 stated that the cumulative value of defence deals between India and Russia since 2018 was US$ 15 billion.22 The Russian arms deals signed during the period 2018–22 are mentioned in Table 3. Table 3. Russian Arms Deals 2018–22 (Leasing/Procurement/Upgrades/License Production)

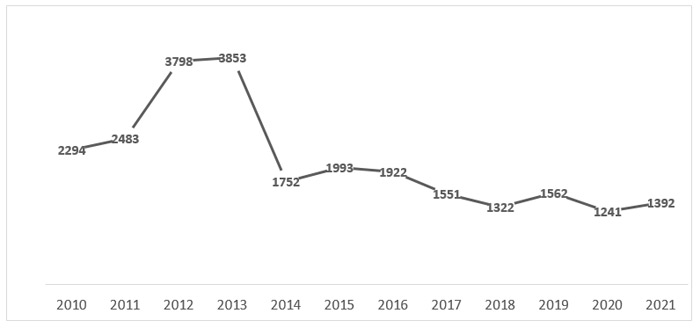

Source: SIPRI Arms Trade Registers; Media reports. Reports in May 2022 flagged that India has halted negotiations for 10 additional Ka-31 early warning helicopters—to the 14 it has in its inventory, due to uncertainties arising on account of US sanctions measures.23 The Indian Air Force’s (IAF) plan to upgrade its frontline Su-30 MKI fighter jets has also reportedly been put on hold.24 US sanctions pressure was also cited as one of the reasons for lack of progress in finalising the deal for the Ka-226T light utility helicopters, powered by French engines.25 Earlier in March 2022, US Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs, Donald Lu, while responding to a question from Democratic Senator Chris Van Hollen whether India’s abstentions at the United Nations on Ukraine-related resolutions will impact the administration’s decisions on a possible CAATSA waiver going forward, stated that India has cancelled orders for Mig-29 fighter jets, anti-tank weapons, and helicopters ‘in just the last few weeks’.26 There has been no formal confirmation, though, from Indian officials, of these cancellations. As for the S-400, India entered into the US$ 5.4 billion deal with the Russian Federation in October 2018 for five units of the system. The first unit was deployed in December 2021 while the deliveries for the second unit began in April 2022. Even as US officials have been maintaining that India should reduce its dependence on Russian equipment, as on date, the US Secretary of State, in consultation with the US Treasury Secretary, has not made the determination for the US President that India’s purchases of the S-400 constitute a ‘significant’ transaction with the Russian defence sector. US legislative support for granting India such a waiver, though, is strong. Republican Senators and Congressmen, led by Senator Ted Cruz, introduced the Circumspectly Reducing Unintended Consequences Impairing Alliances and Leadership Act of 2021 (CRUCIAL) legislation in both the Senate (October 2021) and the House of Representatives (November 2021), urging the US President not to impose CAATSA sanctions for a 10-year period, if he certifies to the US Congress that India is cooperating with the US on ‘security matters that are critical to United States strategic interests’ in the Indo-Pacific.27 Republican lawmakers, though, have been critical of India’s voting stance at the UN on Ukraine. At the Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing in March 2022, Senator Cruz enquired from Assistant Secretary Lu if India’s votes reduced the incentives for the US to continue to consider the CAATSA sanctions waiver.28 The amendment was passed with 330 members voting in favour (214 Democrats and 116 Republicans) and 99 against (5 Democrats and 94 Republicans).30 Representative Khanna, a Democrat from California, affirmed that the amendment was the most significant bipartisan legislative action pertaining to India–US relations, since the 2005 nuclear deal.31 While the US President will still have to provide the waiver, the amendment is an important indication of strong bipartisan support that acknowledges India’s need to ‘maintain its heavily Russian-built weapons systems’.32 Analysts have also flagged possible issues that Indian and Russian defence joint venture companies could face in fulfilling export orders or in bagging new orders.33 India entered into a US$ 375 million contract with Philippines in January 2022, for the supply of the Brahmos missile system. The Office of Foreign Assets and Control’s (OFAC’s) ‘50 per cent rule’, states that sanctions will be imposed on ‘any entity owned in the aggregate, directly or indirectly, 50 percent or more by one or more blocked persons’.34 Brahmos JV is not owned 50 per cent or more owned by the Russian JV partner, NPO Mashinostroyenia (which is under US sanctions since 2014). Recent reports have also noted that Indonesia was in advanced talks with India to procure the Brahmos missile.35 The trend indicator values (TIV) of Russia’s arms exports to India during the period 2010–21 are mentioned in Figure 1. Figure 1. Trend Indicator Values of Russia’s Arms Exports to India 2010–21 (in US$ Mn)

ConclusionUS and EU sanctions have had implications for countries that import major Russian defence equipment. Turkey, India and China are pertinent examples in this regard. India could not conclude key arms procurement contracts like those for light utility helicopters, on account of US sanctions pressure, among other issues. Reports have highlighted how it could face issues with regard to paying for contracted weapons systems, for instance. Major purchases like the S-400 system have been under the sanctions cloud, though legislative support in favour of the US administration providing sanctions waiver has gathered momentum. While suggestions to overcome these complications in the near and medium-terms have included the possible creation of escrow accounts and delayed payments, for the longer term, there is no denying the fact that the country’s ‘Aatmanirbhar’ drive for achieving defence self-reliance will have to be further strengthened. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Defence Economics & Industry | United States of America (USA), European Union, EU-Russia Relations, Russia, US-Russia Relations, Defence Diplomacy | system/files/thumb_image/2015/sanctions-on-russia-t.jpg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sri Lankan Economic Crisis and Rise of Left Politics: Implications for India | July 21, 2022 | Smruti S. Pattanaik |

Though the Janatha aragalaya (people’s struggle) against the Rajapaksas was spontaneous, the role of the Left organisations in galvanising this into a movement that ousted the Rajapaksa family is an important landmark in Left politics. Leftist political parties and organisations have always ideologically appeared to be sympathetic to the aspirations of masses. At the grassroots level, they make people aware of their socio-economic rights and thereby manage to create a support base, which can be exploited to mobilise the masses.

The resignation of President Gotabaya has strengthened people’s power. The FSP which has been at the forefront of this struggle now argues for the establishment of People’s Power Councils at all levels—from village to urban areas—as a consultative body that will advise the government. Their argument is that people who have brought this political change cannot be ignored. Gunaratnam, the leader of FSP, asserts that ‘people’s power, as a new pillar, could not be disregarded. …Our long-term goal is to structurally strengthen an external force parallel to the democratic-trinity’.7 Implications for IndiaPolitical instability in the neighbourhood has always been a major concern for India. As the closest neighbour of Sri Lanka, with an emphasis on ‘neighbourhood first’, India has stepped in to provide US$ 3.8 billion credit line consisting of essential items as economic crisis deepened in April this year. Yet, there are several instances where attempts were made to drag India to the ongoing political crisis and portray it as a supporter of the Rajapaksa regime.

It is important to note while in Colombo, people from all walks of life irrespective of religion and ethnicity participated in the uprising, one did not see such mass movement in the north and East. According to an analyst,

The existential problem for the Tamils is their political aspiration. Not surprisingly, many rejected the Rajapaksa government’s much-touted argument of economic prosperity eliminating political alienation of Tamils. India’s stance on the Tamil issue shapes the public opinion of Sinhalese on India. It is important for India to ensure that it continues to provide aid to overcome the humanitarian crisis caused by economic mismanagement of the previous regime. It is also clear that no other countries have extended any major help to the people who are struggling to make both ends meet. While the IMF financial relief may take some time, India must continue to extend help to the people of Sri Lanka while keeping itself away from the antagonistic domestic politics. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

South Asia | Sri Lanka, Economic Crisis, India | system/files/thumb_image/2015/sl-economic-crisis-rajaspaka-t-1.jpg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political Uncertainty in Sri Lanka: No End in Sight | July 21, 2022 | Gulbin Sultana |

Sri Lankans who have been chanting ‘Gota Go Home’ for the last three months finally succeeded in making President Gotabaya Rajapaksa resign from the post on 14 July 2022. The decision of Gotabaya, conveyed via email to the Speaker of the Parliament from Singapore, is being seen as a euphoric victory by the protesters who had occupied the residences of both the President and the Prime Minister as well as the President’s secretariat on 9 July. While Gotabaya’s resignation will go down in history as one of the successes of non-violent public protest, it is unlikely that the resignation alone will bring the desired political outcome and the much-needed economic relief to the people—which was the main purpose of the Aragalaya, the peoples’ struggle. Wrath against the RajapaksasUnprecedented economic crisis led to political chaos in the country in the month of April, with common people in large numbers coming onto the streets demanding resignation of President Rajapaksa and his government. They held the government accountable for contributing to the crisis by implementing faulty economic policies and failing to provide effective solutions. In addition, imposition of family rule, nepotism, corruption, discriminatory racial policies and authoritarian style of governance made the Rajapaksa family a subject of public rage. The public anger erupted and took the shape of mass protests when the shortages of food, fuel, medicine and other essential items due to foreign reserves crisis affected the lives of each and every individual in the country. The anti-government public protests compelled the Rajapaksas, who include Sports Minister Namal Rajapaksa, Finance Minister Basil Rajapaksa, and PM Mahinda Rajapaksa, to resign in April and May. However, Gotabaya Rajapaksa was determined to not resign from the post of president without completing his first term. He committed that he would appoint a national unity government (NUG) or an all-party government under a consensus prime minister to address the protestors’ concerns. Following the resignation of Mahinda Rajapaksa on 9 May, he went on to appoint Ranil Wickremesinghe as the Prime Minister without consultations and formed a government of selected few backed by the ruling party instead of an all-party government, as promised. There was public outcry and dissatisfaction over the appointment of Ranil Wickremesinghe as the PM, as he is not an elected member of the Parliament, with Gotabaya Rajapaksa continuing as the President. The protestors, civil society members, the clergy and professional groups like Bar Association of Sri Lanka (BASL) and opposition parties, continued to demand the president’s resignation. They proposed an all-party interim government for 18 months to provide immediate economic relief to the people and make necessary changes in the constitution to reduce the power of the executive president and eventually abolish the executive Presidency.1 President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Prime Minister Wickremesinghe failed to positively respond to these demands and take measures to address them. The Wickremesinghe government voted out the opposition’s motion to debate displeasure against President Rajapaksa and his government in the Parliament. The government’s draft amendment bill to reduce the power of the executive by repealing the 20th amendment and restoring the 19th amendment also indicated lack of genuine desire of the ruling party and the government to reduce the power of President. Similarly, bills passed in the last one month show that the government was not serious about improving the governance issue. Instead of giving economic relief to the people, Wickremesinghe declared in the Parliament that the economy has completely collapsed and asked the people to brace for tougher times ahead. The plight of the people increased further in the month of June and July under the new government as fuel distribution stopped completely. Wickremesinghe, despite good rapport with the international community, particularly the Western countries, could not bring required foreign assistance to deal with the ongoing crisis. On 29 June, ‘Gota Go Gama’ protestors had a meeting with the leaders of the opposition parties and they agreed to take collective action to intensify the pressure to remove Rajapaksa from power. There was a call from the protestors to the people across the country on social media to gather in Colombo and march towards the President’s secretariat and occupy it on 9 July. Several opposition political parties, trade unions and inter university students’ association too urged people to participate in the protest march. People across the country responded overwhelmingly and occupied the president’s residence, the presidential secretariat as well as the PM’s residence known as ‘Temple Trees’, without facing resistance from the armed forces on 9 July. The all-party leaders in a special meeting on 9 July chaired by the Speaker of the Sri Lankan Parliament agreed on immediate resignation of the president and the prime minister. Rajapaksa conveyed through the speaker, his decision to agree to the demand of all-party leaders and stated that he would resign on 13 July. PM Wickremesinghe too announced his intention to resign. However, neither Rajapaksa nor Wickremesinghe tendered their resignation on 13 July. Rajapaksa fled the country on a Sri Lankan Airforce Jet to the Maldives on 13 July and appointed Ranil Wickremesinghe as the acting president in his absence.2 On 14 July, Gotabaya Rajapaksa went to Singapore in a private jet from the Maldives and tendered his resignation through email to the speaker only after landing in Singapore. Aragalaya ContinuesThe failure of the president to resign on 13 July and the news of appointment of Ranil Wickremesinghe as the acting President created more unrest in Colombo. The protestors occupied the PM’s office and also reached the Parliament where violent clashes broke out between the security personnel and the protestors. Nearly 42 persons were injured during clashes including a soldier and a police constable. Reportedly, anti-government protesters confiscated a T-56 weapon and 2 magazines with 60 rounds of ammunition from an Army soldier during protests near the Parliament.3 The Aragalaya protest has been mostly peaceful, except a few cases of violence. However, developments following the occupation of president’s residence were concerning. On 9 July, Wickremesinghe’s personal residence was burnt down. There were also reports of protestors destroying artefacts in the president’s residence and secretariat. There was also a report of protestors attempting to take over the Rupavahini corporation. Though no violent method was used, protestors insisted the officials of the state media corporation to telecast the views of Aragalaya protestors only. The unruly behaviour of some of the protestors was widely condemned. The Bar Association of Sri Lanka (BASL), the Archeology Department, Free Media Movement, the general public and the sympathisers as well as members of international community urged the protestors to refrain from destroying public property and resorting to violence.4 Ranil Wickremesinghe as acting president imposed emergency rule in the country, imposed curfew in the Western Province and empowered the military to use force to protect state property and human lives.5 On 14 July, activists representing the ‘Gota Go Gama’ campaign, respecting the public opinion and request of the BASL, withdrew peacefully from the president’s official residence, the prime minister’s official residence, Temple Trees, and the Prime Minister’s Office in Colombo.6 However, they stated that they would continue to occupy the front part of the Presidential Secretariat and the Galle Face Green to further continue their struggle until their demands were met.7 Other than the resignation of Rajapaksa government and end of Rajapaksa family rule, the demands of the Aragalaya protestors as outlined on 11 July include the following:8

What lies ahead?So far, the protestors have achieved their demand for resignation of the president and the end of Rajapaksa family rule. However, they seem to be utterly disappointed by the fact that Gotabaya has now been replaced by Ranil Wickremesinghe, who was rejected by the people in the last election and had entered the Parliament through his party’s national-list seat. Wickremesinghe, who once extended his solidarity with the ‘Gota Go Gama’ protestors and expressed his desire to engage with them, had also empowered the military, as acting President, to use force against those acting in a riotous manner.9 The failure on the part of Gotabaya and Ranil to tender resignation on 13 July as committed, led to intensification of the unrest. To maintain law-and-order situation in the country and control the popular uprising, government needed immediate political solution. However, the acting president has felt it prudent to empower the Armed Forces to exercise force to secure public property and human lives, rather than facilitating a political solution by tendering his resignation immediately. All-party leaders in their meeting on 9 July agreed that President Gotabaya and PM Wickremasinghe would resign immediately, following which Parliament would be convened in seven days to appoint an acting president (as per constitutional provision, speaker would be appointed as acting president); then an interim all-party government would be formed under a new Prime Minister; and then elections can be called within a short period of time and a new government can be appointed. Later, when Gotabaya (through the speaker) and Ranil Wickremesinghe confirmed that they would resign on 13 July, all party leaders during a meeting on 11 July decided that the Parliament would be summoned on 15 July, nomination for the President would be received on 19 July and the Presidential election in case of more than one nomination would be held on 20 July through secret ballot. This would be followed by an all-party government under a new President for the future constitutional framework to be carried out and for the continuation of the existing essential services in the country.10 Due to delay in Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s resignation, parliament could not be convened on 15 July and the Presidential election was finally held on 20 July, as decided. With the opposition political parties not able to nominate a common candidate, Ranil Wickremesinghe was elected as the 8th President of Sri Lanka on 20 July 2022, and is expected to complete the remainder of the term of the former president, Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Even though all political parties have agreed to form an interim government, it is uncertain whether the parliamentarians will be able to come to a consensus to appoint an interim PM or elect a President and a national unity government/all-party government that is acceptable to the people. This uncertainty looms large as the ruling party still holds the majority in the Parliament and opposition parties are not united even if they had common demand of ousting the Rajapaksa government and bring about changes in the political system. Since April this year, despite the Aragalaya on the streets, parliamentarians have not felt the urgency to show some political will to address people’s concerns. The parliament in May passed the electricity amendment bill, which ended the bidding process to award contract for energy projects. This is contrary to the demand for introducing transparency to address the corruption and poor governance. The political parties have agreed to curtail the power of executive Presidency. However, three different draft bills for the purpose were put forward in the Parliament as different political parties have different takes on the issue. Majoritarianism and politics based on ethnicity and racial divide are the key features of Sri Lankan politics that have empowered many of the corrupt leaders. As a result, many parliamentarians would like to maintain the status quo and may not give their consent to any systemic change. The NUG experiment in Sri Lanka during the period 2015–19 utterly failed as political parties simply refused to be united even on matters related to highest level of national security concern. Almost same bunch of leaders are continuing in the parliament. This leaves little room for optimism that things will stabilise soon in the coming days. Without political stability, there is little hope for economic stability. To meet the immediate economic needs of the people in terms of supply of food, fuel, medicines and deal with the economic crisis, the island requires financial assistance from multilateral institutes as well as bilateral partners. Sri Lankans are relying heavily on finalisation of the IMF bailout package. UN, World Food Programme, World Bank and some bilateral partners have committed humanitarian assistance, but assistance from some countries including US and Japan will depend on the successful negotiation of IMF deal. An unsettled and unstable government will not only delay the negotiation process, but also affect the implementation of the IMF conditionalities including the debt restructure negotiation with the creditors, improving the governance system and so on. In addition to the financial aid and assistance, Sri Lanka needs to implement policies to revive its economy by strengthening various sectors including tourism, remittances, export, agriculture, investment and so on. Political stability and a settled government are the prerequisite to revive the economy. ConclusionThere is a bleak possibility that the economic, political, and social aspirations of the protestors will be fulfilled anytime soon. Hence ‘Janatha Aragalaya’ is likely to continue for some more time. Though the protestors are determined to continue the struggle through peaceful means, there is a possibility that as the protest continues, a section in the society that believes in anarchy or in adopting violent means to bring required political changes takes over and decides the nature and scope of the Aragalaya. Alternatively, there may be also an attempt to sabotage the people’s peaceful struggle by instigating violence. The main onus to prevent any such situation lies not only on the perseverance of protestors who truly believe on the strength of the peaceful protest, but also Ranil Wickremesinghe and all the 224 parliamentarians who seem to be trying the patience of the protestors. Many in the Western media have raised the possibility of military takeover. This is unlikely given that the Sri Lankan military is usually subservient to the political forces (even though there was an incident of failed military coup in 1962). Further, the depth of the ongoing economic crisis may not encourage the military to take over as it is well known that there is no easy solution to the crisis. To address the question of political legitimacy and to effectively execute and implement plans to deal with the economic crisis and bring to an end to the popular uprising, the prudent option for Sri Lanka is to go for fresh elections. However, the situation right now is not economically conducive to conduct the elections. Elections can ideally take place only after an all-party leadership strikes an agreement with the IMF and other bilateral and multilateral partners, and eases the economic pressure on the people. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

South Asia | Sri Lanka, Economic Crisis | system/files/thumb_image/2015/sri-lanka-politics-t.jpg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turkmenistan’s Neutrality-Based Foreign Policy: Issues and Challenges | July 20, 2022 | Jason Wahlang |

Turkmenistan follows what it terms as a ‘Neutrality-based Foreign Policy’. Aspiring to be the Switzerland of Central Asia,1 it has attempted to stay out of regional political and economic organisations. In 1995, the United Nations General Assembly even adopted a resolution, A/50/80, recognising and supporting the neutrality of Turkmenistan.2 The Ukraine conflict, though, has had significant regional impact, particularly so for Central Asian nations like Turkmenistan. With a strong dependence on Russia, the country’s foreign policy stance of ‘positive neutrality’ will be under the scanner. Isolationism is broadly a strategy that combines a non-interventionist military posture and state-centric economic nationalism.3 States believe that their national interests are best served by isolating themselves from the external environment.4 In a globalised, interconnected, and interdependent world, it is a rare sight to find nations that have decided to exclude themselves from one another. This was, however, not the case in the past. Some of the examples of countries that followed an isolationist foreign policy are 17th century China, 18th century Japan, and 19th century Korea.5 During the two World Wars, the United States did not join the League of Nations and refused to be involved in foreign conflicts, in the initial phases.6 In current times, North Korea has an isolationist foreign policy. Neutrality, as against isolationism, is when a state declares non-involvement in a conflict or war and refrains from supporting or aiding any side.7 It is commonly practised by small states as a means to opt out of the great power politics. Neutrality, however, has its limitations, particularly during periods of war. Neutrality in the past was quite prevalent in the European context, in conflict management and promotion of non-military security solutions. The following sections briefly examine Turkmenistan’s foreign policy after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, under Saparmurat Niyazov, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov and Serdar Berdimuhamedov, to place in perspective its efforts in following a neutrality-based foreign policy. Foreign Policy under Saparmurat NiyazovAfter the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Turkmenistan gained independence, along with the other ‘Stans’. Most of the leadership in the region comprised of local political elites who were former leaders of the Communist Party of Soviet Union. Saparmurat Niyazov, the first leader of newly independent Turkmenistan, was the Secretary of the Communist Party of Turkmenistan before its independence. Niyazov converted one-party Communist rule to rule of ‘Democratic Party of Turkmenistan’.8 Turkmen nationalism replaced Soviet nationalism, providing space for an authoritarian leadership style. Dissent was suppressed, media was under tight control, freedom of movement and access to the outside world was restricted.9 After an alleged assassination attempt on Niyazov’s life, in 2002, stricter border control measures were initiated and dual citizenship of Russian citizens was abolished.10 The cloud of isolation was not limited to Turkmen domestic affairs. There was a sense of isolation in the international arena too. The nation attained the membership of only a few international and regional organisations like the United Nations (UN), the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and Organisation for Security and Co-Operation of Europe (OSCE). Turkmenistan was also reticent when it came to joining regional organisations. It is not a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), and in 2005, it left the permanent membership of CIS and became an associate member.11 Turkmenistan is the only Central Asian nation not to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).12 The country avoided multilateral regional organisations and only sought economically advantageous bilateral alliances.13 Turkmenistan under Niyazov, though, joined the Caspian Five grouping—made up of Russia, Iran, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan—which had its first summit in 2002. This grouping meets every four years at the Summit-level. Relations with neighbouring countries like Iran and Afghanistan were amicable, even during the Taliban regime. Whereas relations with its Caspian neighbour, Azerbaijan, were sour due to disputes concerning oil fields (Serdar, Osman and Omar). There was a transactional relationship with Russia and cooperation was limited to the energy sector. A significant marker of the Niyazov era was the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Resolution of permanent neutrality for Turkmenistan in 1995. The Resolution stated that it recognised and supported the status for permanent neutrality declared by Turkmenistan and called upon states of the UN to respect its independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity.14 Neutrality is also part of the Constitution of Turkmenistan, adopted by the People Council on 27 December 1995.15 Article 1 states that permanent neutrality shall be the basis of its national and foreign policy.16 ‘Turkmenbashi’ Niyazov believed that interdependence threatens sovereignty and nationalism in the era of globalisation and believed that neutrality would eliminate unhealthy competition for the country’s resources.17 Until his demise in 2006, he ensured that involvement in regional affairs was minimal. Foreign Policy under Gurbanguly BerdimuhamedovAfter the death of Niyazov, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov became the president and continued his predecessor’s policies in the domestic sphere but made an effort to improve relations with neighbours.18 In 2008, the Constitution was amended to state that the foreign policy of the country would be based on the idea of ‘permanent neutrality’.19 This policy, present till 2013, intended to improve relationships with neighbours with common economic, historical and cultural ties, including countries like Iran, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan and Afghanistan.20 The Turkmen Ministry of Foreign Affairs organised conferences like the ‘Great Silk Route Diplomacy: From History to the Future’, wherein delegations from 23 countries, including India, China, the US, Iran and Russia, participated.21 This showed the country’s intent to become a major player in the region’s connectivity and trade diplomacy initiatives. This foreign policy stance of enhanced regional engagement, though, came up against energy dynamics. In 2016, Gazprom ceased importing Turkmen gas into Russia.22 After the Russian exit, Turkmenistan’s dependence on China gained traction. The Central Asia–China Gas Pipeline currently accounts for the lion's share of Turkmenistan’s foreign exchange earnings.23 In 2017, Gurbanguly decided to make the next big step on positive neutrality. The president stated that for the next seven years, Turkmen foreign policy would be based on multi-format cooperation with international organisations.24 In 2019, relationship with Russia changed for the better, with Gazprom resuming purchase of Turkmen Gas.25 This was considered an important step towards reducing dependence on China. Foreign Policy under Serdar BerdimuhamedovOn 12 March 2022, Serdar Berdimuhamedov, son of the former president, was elected as the President of the Central Asian republic, at a time when the entire region is in turmoil due to the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. He was the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs under his father’s leadership. In the first few months, Berdimuhamedov has upped the ante regarding diplomatic engagement with regional and international actors. In April, he sought financial assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).26 Due to the Russia–Ukraine conflict, the resultant sanctions on Russia have had a trickle-down effect on the Central Asian economies as well. According to the World Bank, the Central Asian economy is forecast to shrink by 4.1 per cent this year, compared to the forecast of 3 per cent before the crisis.27 Moreover, Turkmenistan’s economic infrastructure has already been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, with inflation being a major concern.28 The Turkmen President visited Russia on 10 June 2022, his first foreign visit since taking charge. Prior to the visit, Berdimuhamedov had called up President Vladimir Putin, on the occasion of 30 years of bilateral relations (both countries established relations on 8 April 1992). The two leaders then had pledged to enhance cooperation in regional formats, like the Caspian Five.29 During his June visit, both sides signed the Declaration of Deepening Strategic Partnership, setting out priorities with respect to trade and investment. One of the significant details of the statement was the collaboration on gas and oil.30 As noted earlier, Gazprom revived its cooperation with Turkmen Gaz in 2019. Apart from Gazprom, Lukoil is also focusing on its 2021 joint venture along with Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan on the Dostluk oil field in the Caspian Sea. Another company which seeks to gain is Russian company Tatneft which, since 2020, has been responsible for the repair and maintenance of oil wells in Turkmenistan. Russian company, United Shipbuilding Corporation, will also assist in the construction of a multipurpose bulk carrier. The need for close cooperation with Caspian littoral states on aspects relating to security, economic partnership and preservation of natural resources as well as cooperation in both bilateral and multilateral formats was stressed. Russia is one of the largest trade partners for Turkmenistan and the new Declaration will enable both countries to diversify their economic cooperation and not just limit it to the energy sector. Turkmenistan wants to diversify its energy exports also and not be dependent on the Chinese market. The second nation that Berdimuhamedov visited since taking over was fellow Caspian nation, Iran, on 14 June 2022. He met President Ebrahim Raisi and Supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei. Nine Memoranda of Understanding were signed, focusing on various spheres of cooperation including trade, economic, scientific, and cultural areas.31 One of the major topics during this meeting was the clearing of the gas debt which was accumulated in 2018. In 2017–18, Turkmenistan and Iran were embroiled in a bitter dispute, with Turkmenistan accusing Iran of faltering on payments that it had to pay for receiving natural gas. Gas supplies to Iran were cut off and both nations approached the arbitration court. During Berdimuhamedov’s visit, it was decided that gas debts would be cleared through the payments Iraq needs to pay Iran.32 Iran has strong historical linkages with Central Asian countries, particularly with regard to the language. The Turkmenistan President also sent a letter to President Joe Biden expressing his intent to expand and strengthen positive engagement. The letter stressed on the need for expanding cooperation, including in fields like aviation, agriculture and banking.33 Turkmenistan has not voted in favour of UN resolutions on Ukraine. As for the country’s relations with Afghanistan, with which it shares a land border, on 22 March 2022, Turkmenistan became the first Central Asian country to recognise the Taliban envoy to the Afghan Embassy in Ashgabat. Foreign Minister Rashid Meredov earlier visited the Islamic Republic in November 2021. During this visit, discussions were held on the Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India (TAPI) pipeline. Defence Minister Mullah Mohammad Yaqoob assured his country’s protection to the TAPI pipeline in the Afghanistan region.34 The project was expected to be completed by 2020 but due to political turmoil in Afghanistan, construction has been delayed. Areas of tension between the two countries do remain. There was a clash between the Turkmen border guards and the Taliban on 3 January 2022 in the Jowzjan province bordering Turkmenistan. The clash according to the Taliban was due to the Turkmen guards killing a civilian prior to the incident and when the Taliban went to investigate, the Turkmen guards fired at them. The Turkmen side did not make any statement with regard to the clash. The presence of the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) further complicates the situation between Afghanistan and Turkmenistan. The ISKP had recently threatened the government in Turkmenistan on 23 June 2022, stating that it should be destroyed. The ISKP, through various social media outlets, has poured scorn over the TAPI gas pipeline and has charged that the Taliban, being supportive of the project, is protecting the interests of the enemies of the religion in Afghanistan. These threats to the Turkmen government and its interests in Afghanistan coupled with the recent attacks in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan ensures that it is even more important for the Central Asian nation to maintain peaceful relations with the Taliban-led Afghan government. Over the past decade, there has been a rising dependence of Turkmenistan on China, a main export market for Turkmen gas.35 This became more visible after the crisis with Russia and Iran which ensured that China became the dominant partner for Turkmenistan in the field of gas. The gas exports to China from Turkmenistan annually are an estimated 40 billion cubic metres (bcm).36 This makes Turkmenistan the third largest natural gas supplier to China, accounting for 40 per cent of its natural gas imports. In 2021, Turkmenistan exported 34 bcm to China, which is a reduction from the annual 40 bcm. This was in the aftermath of the restart of Russia–Turkmen gas relations in 2019. This does indicate that Turkmenistan has managed to reduce its dependence on the Chinese export market and in the long run, can be expected to further diversify its exports. As for political interactions, Chinese Defence Minister Wei Fenghe visited Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan in April 2022, with the focus of discussions pertaining to cooperation in the military field, including on provision of equipment and personnel training. In recent years, Turkmenistan–China military relations have been developing steadily, an equation which could generate tensions given the traditional security role played by Russia in these Central Asian republics. ConclusionBerdimuhamedov’s limited time in office demonstrates that he has engaged with key regional countries like China, Russia, Iran and Afghanistan, while keeping channels of communication open with the US. It remains to be seen the manner in which Turkmenistan’s new leadership maintains the country’s stated foreign policy doctrine of Greater Neutrality Policy, in the current fluid geopolitical situation arising out of the Russian military intervention in Ukraine. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Europe and Eurasia | Turkmenistan, Foreign Policy, Russia-Ukraine Relations, Central Asia, Central Asian Republics (CARs) | system/files/thumb_image/2015/Turkemenistan-President-palace-Ashgabat-t.jpg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iran’s Central Asia Policy Gains Momentum amid Russia–Ukraine War | July 19, 2022 | Deepika Saraswat |

On 18 June, the first freight train carrying Kazakhstan's sulphur cargo destined for Europe arrived in Iran from Incheh Borun at the Iran–Turkmenistan border.1 A day later, the cargo reached Tehran, where President Ebrahim Raisi, along with the visiting Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev launched the Kazakhstan–Turkmenistan–Iran (KTI) transit corridor, also called the Southern Caspian Sea Corridor to Europe via Turkey.2 Just a week before Tokayev’s visit to Tehran, President of Turkmenistan, Serdar Berdimuhamedow, also visited Tehran, signing bilateral agreements for advancing economic cooperation, especially in transit and transportation sectors as well as oil and natural gas. Iran in Eurasian ConnectivityPresident Raisi’s administration has prioritised neighbourhood policy as a key pillar of ‘resistance economy’, which is aimed at reducing vulnerability to sanctions. Recently, describing it as ‘strategic’ policy, Raisi argued that neighbourhood focus will not change with international developments.6 Raisi’s first official visit abroad was to attend the summit of Economic Cooperation Organisation (ECO)—made up of Central Asian and Caucasus states, apart from Iran, Turkey, Pakistan—in Ashgabat in November 2021. On the sidelines of the summit, Iran, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan signed a tripartite Memorandum of Understanding on railroad cooperation.7

Map 1. Map of Iran Railway

Source: Map of Iran Railway, The Railways of the Islamic republic of IRAN, August 2014. Iran–Turkmenistan–Kazakhstan railway, also called the North–South railway corridor because it’s part of the INSTC, has been a work in progress for years. The 80 km railway line from Incheh Borun on Iran–Turkmenistan border to Gorgan in Iran’s Golestan Province was inaugurated in December 2014.8 Given that the Incheh Borun–Gorgan railway line connects railway networks of Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Iran, and is aligned with Russia’s objective of North–South transport corridor through Central Asia and Iran to India, Russian Railways had signed an agreement with Iranian railway in 2017 to carry out the electrification of 500 km stretch from Incheh Borun to Garmsar on the Tehran–Mashhad main line. This project was to be funded from a US$ 5 billion Line of Credit from Russia for infrastructure projects in Iran. Russia withdrew from the project in 2020, but it pledged to revive the credit line during Raisi’s visit to Moscow in January 2022. Iran’s Drive for Regional Security CooperationIn the wake of the Russia–Ukraine War, Iran blamed NATO’s eastward expansion for creating tensions, while calling for dialogue and diplomacy to resolve the crisis. In a telephonic conversation with President Putin soon after the beginning of Russian operation in Ukraine, Raisi noted that “the expansion of NATO is a serious threat to the stability and security of independent countries in different regions”, underscoring Iran and Russia’s shared security objectives in limiting the Western influence in the region. Both Iran and Russia have supported dialogue and cooperation among regional countries on issues ranging from the Caspian Sea to Afghanistan and terrorism, and share membership in a number of multilateral regional groupings.20 Their geo-economic and geopolitical conception of Eurasia is based on advancing connectivity and security cooperation among regional states and exclusion of extra-regional players. ConclusionThe Raisi administration, which has delinked Iran’s economic policy to the revival of JCPOA, has focussed on economic diplomacy with ‘Eastern’ powers of Russia and China and has taken measures to improve infrastructure connectivity with Central Asian neighbours. The disruption in international transportation routes caused by neighbouring European countries closing their borders with Russia and Belarus has led Russia, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan to prioritise transport and transit cooperation with Iran, giving a fillip to Iran’s geo-economic status in Eurasia. In geopolitical terms, instead of making a departure from its traditional Russia-centric Central Asia policy, where Tehran acknowledged Russian leadership as ‘a counter-hegemonic power or a Eurasian balancer’, Iran’s growing geo-economic and security role in Central Asia appears to be proceeding within the parameters of their convergent vision of Eurasia. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Europe and Eurasia | Iran, Central Asia, Russia-Ukraine Relations, Trade, Europe, China | system/files/thumb_image/2015/iran-t_0.jpg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political Impasse in Lebanon | July 18, 2022 | Jatin Kumar |

The general elections held in Lebanon on 15 May 2022 failed to determine a clear winner, thus ensuring no end to the political uncertainty. Over a month after the elections, President Michel Aoun finally tasked the caretaker Prime Minister, Najib Mikati, with the responsibility of forming a new government. Mikati was backed by 54 out of 128 parliamentarians.1 While Nawaf Salam, Lebanon’s former ambassador to the United Nations, received 25 votes, 46 MPs abstained from naming any candidate.2 The elections happened at a time when the country is in the midst of a major economic and sectarian crisis. The elections sparked a ray of hope among the people that it could perhaps bring in some relief from the economic hardships and corruption plaguing the country. The government’s proposal to increase taxes on WhatsApp, gasoline and tobacco in 2019, triggered widespread protests which have continued to occur intermittently since then. The formation of a stable government was also crucial as it can secure support from the international community. The United Nations, United States, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Lebanon’s former colonial power, France, have time and again emphasised that their support is conditional on the political leadership undertaking economic reforms at the earliest. Parliamentary Elections 2022Lebanon follows an open list proportional representation system to elect the 128 members of parliament for a four-year term.3 Its political system functions on confessional basis, which means that the key political positions such as that of the President (Maronite Christian), Prime Minister (Sunni) and Speaker of parliament (Shia) are reserved on religious and sectarian lines. To form a new government, nationwide parliamentary elections were held on 15 May 2022. The voter turnout was recorded at nearly 50 per cent.4 The low voter turnout was surprising for many experts as they expected that protests and anger among the Lebanese citizens against the government will drive them to participate in the elections more vociferously. In comparison to the 2018 election, the 2022 election registered a large number of candidates willing to contest for the opportunity to enter the parliament. According to the Interior Ministry, 718 candidates (20 per cent higher than the 2018 elections) and 103 lists of registered candidates contested in the elections, including 118 women candidates.5 The increase in the number of candidates (from 77 in 2018 election) and lists can be linked with the decision of former Prime Minister Saad Hariri to not contest the election, thereby providing space for independent and civil society list candidates to fight for the Sunni votes. Furthermore, political protests which have taken place in the country since 2019, gave rise to various local leaders entering the political scene, and have contributed to the increased number of candidates in this election. The most surprising aspect of the election results was the decline in the number of seats of Hezbollah allies. Pro-Hezbollah independents and allies could secure only eight seats as compared to 15 in the 2018 elections. Although Hezbollah allies have lost their majority, the parliamentary seats of Hezbollah remain unchanged. This reveals a minor and temporary loss of popularity.6 Lebanese Forces, a Christian political party, and its allies won 21 seats, up from 15 in 2018. President Aoun’s Christian Free Patriotic Movement and its allies also registered a fall in their support and secured only 18 seats as compared to 29 in 2018.7 In addition, Saad Hariri’s surprising withdrawal from the election adversely impacted the performance of Future Movement Party which could only secure seven seats in comparison to 20 in the previous parliamentary election. Though Hezbollah's allies have lost seats in the parliament, one should not undermine their role in government formation as Hezbollah and Amal together account for 28 seats (Hezbollah 13 and Amal 15) in the parliament. However, government formation will be a difficult task as none of the political parties or alliances has secured a clear majority in the new parliament. With regard to Hezbollah, the election results also falsified the “predictions of mass voter desertion from the Shia camp” due to the economic meltdown.8 The improved performance of the civil society and activists also came as a pleasant surprise as they secured 13 seats, in comparison to one seat in the previous election (see Table 1). However, the gains of anti-Hezbollah opposition are insufficient to generate any major shift in the parliament.9

Table 1. Parliamentary Elections: Party Positions

Source: “Lebanon Election Results 2022 in Full: Which Candidates and Parties Won?”, The National News, 17 May 2022. What the future holdsThere is no doubt that Lebanon needs a major economic and political overhaul to halt the ongoing systemic collapse, as has also been suggested by the UN, France and the IMF, time and again. However, large-scale changes cannot be expected from the new parliament. This is mainly because Lebanon’s traditional parties such as Hezbollah, Amal, Free Patriotic Movement and others are not ready to bring any major shift in their policy stance.10 They have constantly undermined the Lebanese economy by indulging in corrupt practices and financial mismanagement, which has resulted in a significant systemic degradation of the country. Furthermore, they have followed policies that have only benefitted the feudal warlords. The parliamentary consultations to decide the new Prime Minister were held on 23 June 2022, over a month after the elections. On 29 June 2022, Mikati handed details of his government to President Aoun, which were leaked to the media. The media reports suggest that majority of ministers from his caretaker government have been included in the list of new ministers. Notwithstanding the above, Lebanon is yet to witness the formation of a new stable government. Based on past experience, government formation process would not be easy and may take a lot of time. In addition, many experts feel that the new government will not help in reversing the country’s economic downturn.11 This is mainly due to the re-election of a majority of old political elites in the parliament, who were responsible for stalling political and economic reforms.12 The current parliament is highly fragmented on the basis of diverse opinions held by various parties. Even those who favoured Mikati during the parliamentary consultations differ on issues such as maritime negotiations with Israel and relations with the Gulf countries. Thus, confrontations on foreign and economic policy and other political matters can be expected. This will result in major policy paralysis at each stage of decision-making and implementation. Furthermore, Hezbollah’s presence in the government can potentially discourage Saudi Arabia from extending economic support to Lebanon. It is no secret that Lebanon’s relations with Saudi Arabia remain tense owing to the Iranian influence in the domestic and foreign policy of the former. Thus, it seems that the parties which have extended support to Mikati, have merely done so for the sake of forming a government, with no intention of introducing the much-needed reforms in the country. Along with the imperative of improving the economic condition of the country, a stable government in Lebanon is also the need of the hour in order to determine its relations with the Gulf countries. The latter will keenly observe the extent of Iranian influence on the functioning of the new government, which has been a major sore point in Lebanon and Gulf countries’ relations, particularly with respect to Saudi Arabia. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Eurasia & West Asia | Lebanon | system/files/thumb_image/2015/lebanon-election-t.jpg |