You are here

| Title | Date | Date Unique | Author | Body | Research Area | Topics | Thumb | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhutan Election Paves Way for Political Transition | February 27, 2024 | Smruti S. Pattanaik |

SummaryThe Tsering Tobgay-led People’s Democratic Party (PDP) won the maximum number of seats in the Bhutan elections and formed the government. Given rising youth unemployment and domestic debt, economic issues dominated the manifestos of the political parties. As Bhutan prioritises economic development, India can be a close partner. Bhutan, a new entrant to the democracy club, witnessed its fourth elections when the country voted on 9 January 2024 to choose a party that will govern them for the next five years. The election to Bhutan’s National Assembly saw the Tsering Tobgay-led People’s Democratic Party (PDP) winning 30 seats. Tobgay sworn in as Prime Minister of Bhutan for the second time on 28 January. He was in power from 2013 to 2018. Bhutan Tendrel Party (BTP) founded by Pema Chewang, a civil servant who had resigned from his position to join politics, is a new entrant to politics. The party won 17 seats mostly from the Eastern Part of Bhutan in the final round of the election. Bhutan has two rounds of election, the primary round which is multiparty and the final round where the contest is between the two political parties that receive the first and second highest votes. The primary round of this election was held in November 2023 in which four political parties participated. All the political parties in Bhutan need to confirm to Section 136 of the Election Act of the Kingdom of Bhutan 2008, which requires the parties to repose faith and allegiance on the constitution, possess a broad support base irrespective of gender, religion and caste with a cross-national membership and which ‘does not receive money or any assistance from foreign sources’ be it private or government.1 Elections in Bhutan are funded by the government unlike other countries of South Asia. Economic Concerns Dominate ElectionsEconomic issues dominated the electoral landscape with each political party pledging development and economic growth in their electoral manifesto. Youth unemployment in Bhutan has increased. In the post COVID-19 environment, the situation has worsened as tourism industry which employees around 50,000 Bhutanese, has been hampered. In August 2023, Bhutan cut its Sustainable Development Fee by 50 per cent to increase tourist footfall.2 According to UNDP, youth unemployment which was 11.9 per cent in 2019 grew to 22.6 per cent in 2020.3 The second main concern relates to the growing domestic debt. Currently, Bhutan has a debt to GDP ratio of 129.1 per cent. As of 31 December 2023, public debt stood at 103.2 per cent of the FY 2023–24 GDP estimate. Of the total external debt, government debt stood at 90.9 per cent which constitutes borrowings for budgetary activities, hydropower projects, and loans, with hydropower debt standing at 66.3 per cent. Yet, hydropower is also the main source of Bhutan’s export earnings.4 Migration of youth is another major challenge. According to an estimate, around 2 per cent of Bhutan’s population has migrated overseas in the last six years.5 Key Highlights of ManifestosIn Bhutan, the election manifestos of the political parties are approved by the Election Commission of Bhutan (ECB) which looks into the promises made by the political parties and the practicality of these promises. This ensures that no political party can make promises that sways the voting and yet finds it difficult to implement. The ECB appoints independent anonymous committee that holds a month-long review of the manifestos. All the political parties are required to file their election expenses to the Public Election Fund Division of the ECB. This provides a fair chance to all political parties to campaign equally. The following section provides key highlights of the election manifesto of the major political parties. Five political parties participated in the first round of the election, while the Bhutan Kuen-Nyam Party (BKP) deregistered itself as a political party in January 2023. Voter turnout in the primary round was 63 per cent as per the data published by the ECB.6 Bhutan has a bicameral legislature—National Assembly and National Council. The apolitical National Council has 20 elected members from dzongkhags (districts) and five members are nominated by the King. The election to the National Council took place in April 2023. Given Bhutan’s tourism potential, all the political parties promised to revisit the Sustainable Development Fund (SDF) levy on the tourists. PDP manifesto provided a roadmap to boost tourism that can employ Bhutanese and generate income. All the political parties pledged to be guided by the vision of His Majesty the King, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. Economic development was the focus of the election manifestos of the five political parties. Druk Phuensum Tshogpa’s (DPT) election manifesto7 revolved around ‘Economic Prosperity and Social Well-Being’. In the context of Gross National Happiness, DPT promised high economic growth, attracting FDI and adopting a national export strategy. The manifesto prioritised Bhutan’s potential as an exporter of hydroelectricity. It promised three new hydro projects with India and also wanted to accelerate trilateral cooperation with India for export of hydropower to Bangladesh which has pledged US$ 1 billion investment in Bhutan’s 1,024 MW Dorjilung hydroelectricity project.8 India’s Guidelines for Cross Border Power Trade were announced in 2019. The PDP manifesto9 spoke of declining birth rate and migration of Bhutanese to other countries that may impinge on Bhutan’s survival and sovereignty. The manifesto also spoke of youth unemployment with a slogan ‘For a Better Druk Yul. The Promise We Will Deliver’. The manifesto mentioned the party’s promise to develop six megaprojects and seven mini hydroprojects. Emphasing on economic revival, PDP promised to introduce ‘Buy Bhutanese Product’, introducing job protection plan in private sector, enabling private sector growth, developing infrastructure for better communication, take steps to enhance ease of doing business and attract FDI. A new party, Druk Thuendrel Tshogpa (DTT) was registered with the election Commission in 2023. In its manifesto,10 it emphasised on ‘Sunomics’ which it defined as Buddhist Capitalism with the spirit of GNH and is based on Five Economic Senses, that is, a governance ecosystem predicated on prosperity based on four elements of the nature Earth, Water, Fire and Air.11 It emphasised on agriculture and pledged to have self-sufficiency in at least ten crops. It promised roof over head by reducing the cost of building material and underlined the need to facilitate ‘PPP in investments, export, credit facilities and faster Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) services from the banks.’ Increase in the foreign currency reserve and promotion of tourism was also one of its agenda. The Bhutan Tendrel Party (BTP) in its election manifesto12 underlined the brain drain that Bhutan was facing and emphasised on economic transformation and jobs creation. It considered investment as vital to growth and job creation and vowed to facilitate investment in Bhutan through public–private partnership. Drawing attention to the per capita increase in debt, it promised to double the GDP growth rate. Given that more than a lakh youth would enter the job market by 2032, the party prioritised skill development to increase employability. The need to manage inflation was emphasised. The party promised to take steps to reduce the existing trade gap, maintain healthy foreign currency reserves, attract foreign investment and manage public debt and its sustainability. Tourism development also found a place in the manifesto. Druk Nyamrup Tshopga (DNT), the party in power till this election, in its manifesto mentioned the impact of COVID-19 on the economy and lamented the limited system that is not capable of tracking trade, connectivity, movement of goods and people, data of Bhutanese travelling abroad, payment and other financial transactions, illegal residents along the border and criminal activities.13 If elected to power, it promised its commitment to Tsa-wa-sum (King–Country–People). It assured that it will streamline the business registration process, make it easier to access capital, reform labour law and protect intellectual property rights.14 Elections ResultsIn the first or primary round of the election, the political parties’ performance with percentage of votes is shown in Table 1. Table 1

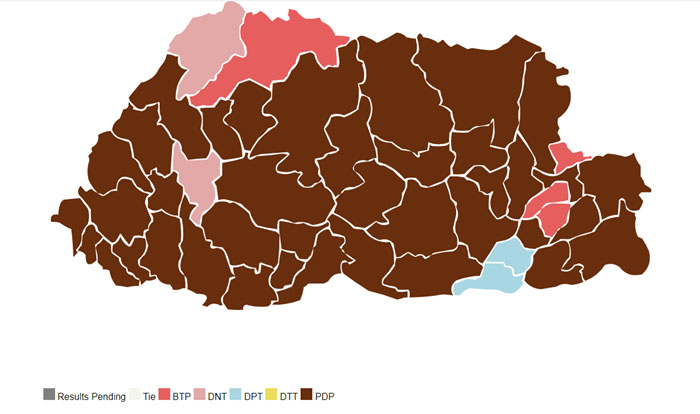

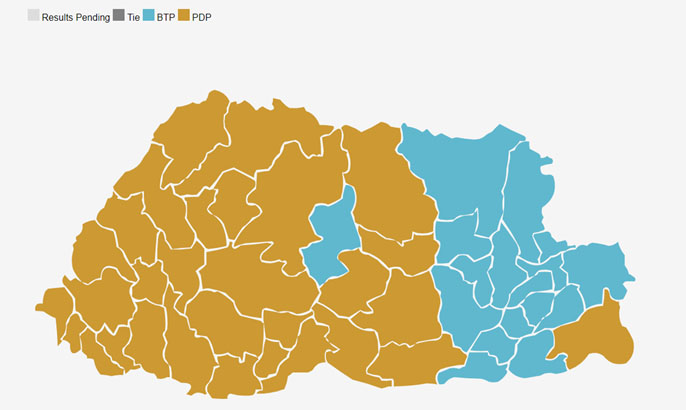

Source: “Declaration of Results of the 4th National Assembly Elections, 2023-2024 (Primary Round)”, Election Commission of Bhutan, 1 December 2023. Map 1 illustrates the electoral spread of political parties. The PDP that won the election dominates the map. Quite interestingly, it won most of the seats in the East, except for five seats which went to the opposition. Out of this, two seats bordering India was won by DPT and three on the northern side were taken by the BTP. Map I

The two major political parties contested the final round of election held on 9 January 2024. The voting pattern reflects interesting distribution. The PDP that had own many constituencies in the East lost to DTP and the PDP also gained in the North West in the final round. Map II

ChallengesBhutan has several challenges to confront. One is drug related which is illustrated from the fact that there were 2,112 arrests in 2023.15 Bhutan last year had suspended two judges and an administrator for their involvement in giving a favourable verdict in a drug related case. Similar is also a spike in number of crimes and many of them are related to substance abuse.16 This young entrant to democracy with Gross National Happiness as its motto has not seen women representation at the local and the national level. There is no structural barrier for women’s participation but the traditional society of Bhutan inhibits women from participation. For example, a report in Keunsel revealed that at the local level, “just 2 women gups as compared to 203 male counterparts, and 24 women mangmis in the total 205 gewogs”.17 Though 23 women contested the National assembly election this year, only two were elected to the current Parliament. The percentage of women candidates was 10.1 per cent in 2018. It dropped to 9.7 per cent of the 235 candidates from 47 constituencies in 2023.18 Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa fielded the highest number of female candidates (7), followed by Druk Thuendrel Tshogpa (6), Druk Phuensum Tshogpa (5), Bhutan Tendrel Party (3) and People’s Democratic Party (2).19 According to Tenzing Lamsang writing in The Bhutanese, debate has also unfolded regarding DTP’s overwhelming win in the East which is attributed to economic backwardness as most of the development and economic activities in Bhutan are concentrated in the Western region. Most of the hydropower projects are also in the western side of Bhutan due to the geographical factor.20 Prime Minister Tsering Togbay has dismissed this division saying that ‘We are one people in one country under one King’.21 The government has decided to place a ban on import of vehicles. Bhutan which has a reputation on prioritising environment conservation is going to move to electric cars. Import of petroleum has put enormous pressure on foreign exchange. According to a media report, “fossil-fuel imports cost the Bhutan Nu 3.3 billion to keep the country’s fleet of 126,650 vehicles, including heavy earth-moving machinery, running. By contrast, the earnings from hydroelectricity export fell by about 70 percent to Nu 218.15 million owing to poor hydrology.”22 As Bhutan prioritises economic development, India can be a close partner. The PDP is vocal about forging a closer relationship with India. During Bhutan King’s visit to India in November 2023, he met business leaders in India to expand economic and commercial ties between the two countries. To bring the economy back on track, Prime Minister elect Tobgay has indicated that he would establish the framework for the Economic Stimulus Plan (ESP) and stated that the “preferred source is grant through Government of India like in the 11th plan”.23 Bhutan is the largest recipient of India’s aid.24 For Bhutan’s 12th Five Year Plan, India’s contribution of ₹4,500 crore constituted 73 per cent of Bhutan’s total external grant component.25 India’s grant project, the 57.5-kilometre railway line between Gelephu and Kokrajhar which is being built at the cost of Rs 10 billion and would be completed in 2026, would help the Bhutanese economy and people-to-people connect. Table 2: India’s Budgetary Support for Bhutan’s Five Year Plans (in Rs crores)

Source: “Economic and Commercial”, Embassy of India, Thimpu, Bhutan. As for Bhutan’s relationship with China, there are reports of China building new settlements inside the disputed border with Bhutan. This settlement is supposed to accommodate 235 households.26 About 25 rounds of Bhutan–China border talks have been held so far. The swapping of territory for a boundary settlement is being discussed. However, Bhutan has assured that it will not take any steps that would go against India’s interest in the tri-junction shared by Bhutan, India and China.27 Both the countries have agreed for three steps’ roadmap signed in 2021 to resolve their boundary dispute.28 The technical committee set up by the two countries on ‘delimitation and Demarcation of the Bhutan-China boundary’ held their first meeting in August 2023. It is expected that there would not be any major foreign policy changes with the new government in Bhutan. It needs to be mentioned that the King continues to play a pivotal role in shaping India–Bhutan relations. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

South Asia | Bhutan, Elections | system/files/thumb_image/2015/bhutan-election-2024-t_0.jpg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First Person View (FPV) Drones: When Quantity Equals Quality | February 27, 2024 | Akshat Upadhyay |

SummaryFirst Person View (FPV) drones have been used by both the antagonists in the Russia–Ukraine conflict. Despite their limited payload capacity and reduced flight time due to their focus on speed and maneuverability, FPV drones are ideal for close quarter battle (CQB) situations. FPV drones combine personalised target selection, accuracy, autonomy, EW resistance and guidance into a single platform, at the fraction of the cost of bigger and more sophisticated platforms. IntroductionThe ongoing Russia–Ukraine conflict has featured use of a host of critical and emerging technologies (CETs).1 Artificial intelligence (AI), drones, unmanned underwater vessels (USVs), facial recognition technology (FRT) are some of the niche technologies that have been leveraged by both sides in an attempt to gain tactical advantages over the other. However, what remains under-appreciated in the strategic literature—at least outside of posts on social media platforms saturated with war footage of the conflict—is the innovative use of certain platforms and technologies. Optimising the use of such technologies requires a combination of scale, training and innovation since the platform is generally a mix of collaboration, convergence and cost-savings. One such platform is the first person view (FPV) drone, whose initial usage by the Ukrainian Armed Forces (UAF) led to a reciprocal response by the Russian forces,2 with a result that the conflict in the region has quite literally become a ‘game of drones’.3 This Brief analyses the FPV drone in detail, documents some of its uses in the ongoing Russia–Ukraine conflict and comments on the future of this technology and platform. FPV DronesFPV drones are aerial drones with an onboard camera whose live feed is streamed directly into the FPV user’s goggles, headset, smartphone device or any other device deemed compatible.4 FPV is a viewing angle where the pilot sees only what the drone sees. There are multiple types of FPV flying such as FPV freestyle (for beginners), cinematic and drone racing (going through a series of obstacles, flags and gates).5 The first amateur drone racing was held in 2011 in Karlsruhe, Germany,6 followed by Australia in 2013.7 The event is now handled by professional racing agencies Drone Racing League (DRL), Airspeeder and MultiGP, among others. FPV racers also use certain exclusive terms within their clique such as bando (abandoned buildings) and orbit (flying in a circular path).8 These drones offer three major advantages: immersive experience for the user/pilot who can see in real-time what the drone is seeing, more precise flying and better accuracy due to low latency transmission. All three characteristics are a boon for the warfighter. Real-time communication, precision flying and accuracy are important attributes of modern warfare. This third dimension flying capability has been leveraged by soldiers in Russia and Ukraine to gain tactical advantages over each other. FPV drones offer other advantages too. They may be assembled with disparate parts from other cannibalised platforms, 3D printed, fitted with bespoke explosives and made ready in a fraction of the time it takes to put together more sophisticated platforms like fighter jets and bigger unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) on industrial assembly lines. An FPV drone, if handled properly, can be visualised as an extremely fast and manoeuvrable, pin-point explosive that can neutralise hard-to-reach targets such as soldiers hiding inside bunkers. It combines the accuracy of a precision-guided munition (PGM) with the mortar round’s ability to locate and hunt targets in defiladed positions (reverse slope of a hill or within a depression in level or rolling terrain). Some obvious limitations, such as limited endurance, payload capacity and range have adverse implications for the soldier, if these are viewed as solely flying platforms. But viewed as alternatives to expensive ammunition with added benefits of manoeuvrability, scalability and cost-effectiveness, these appear as lucrative acquisitions in modern warfighting. FPV vs Regular DronesThere are five key attributes in which FPV drones differ from regular drones. Control and PerspectiveRegular drones operate on a line-of-sight principle when a pilot is in charge or through GPS/GNSS receivers, inertial navigation systems (INS), LiDAR scanners, ultrasonic sensors and visual cameras when in autonomous or semi-autonomous mode. The drone pilot can view the flying drone (for tactical drones) directly or look at its video feed on a console or screen. The camera of a regular drone is generally underslung and mounted on a gimbal which allows for rotation of the camera and in-flight stabilisation. FPV drones, on the other hand, provide the operator with a first person view, simulating the experience of flying from the drone’s cockpit. This is achieved by streaming the feed directly into the goggles or headset of the operator. Manoeuvrability and SpeedRegular drones have the capability to hover and maintain a stable path, making them ideal for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) missions where steady footage and detailed environmental scan are required. FPV drones rely on speed, compactness and extreme maneuverability—ideal for close quarter battle (CQB) situations such as counterinsurgency/counter terrorism (CI/CT) scenarios. Payload and EnduranceRegular drones, depending on their type, have a larger payload capacity and endurance which allows them to be used for complex missions involving multiple sensors and coordination with other entities and platforms. FPV drones have limited payload capacity and reduced flight time due to their focus on speed and maneuverability. Their payload is generally an onboard camera (or two) and bare minimum additional equipment. They are ideally suited for kamikaze or one-way missions. Operational UseThere is partial overlap between regular and FPV drones in terms of operational use, in that both categories are used for ISR and kinetic missions. The difference is in the nature, complexity and size of the terrain or battleground. While the former is used over a wide geographical area for gathering intelligence or to monitor ongoing operations, the latter is used in complex, congested, or close quarter situations which may involve small-scale precise tactical strikes. Technological Complexity and CostRegular drones can be more technologically sophisticated, incorporating advanced navigation systems, autonomous capabilities, and high-definition sensor suites. This complexity often results in a higher cost per unit. FPV drones place more emphasis on manual control and agility, relying less on autonomous navigation and complex sensor payloads. Sub-systems of FPV DroneFPV drones are made up of four major component groups which are frame, flight system, power system and the FPV system. FrameThe frame is the base or foundation of the FPV drone and all modifications and attachments to the drone have to be done based on the design of the frame. The frame is made up of carbon fibre. There are three attributes that need to be kept in mind when designing a frame for an FPV: frame shape (True X, Wide X, Stretch X, Hybrid X, Dead Cat, H, HX, Z, Plus and Vertical Arms), wheelbase (varies between 65mm to 280mm) and mounting holes.9 Flight SystemFlight system components include flight controllers (FCs), electronic speed controllers (ESCs), motors, propellers or props, radio and receiver. While the flight controller is generally considered the brain of the FPV drone and has sensors like gyroscopes, accelerometers, barometers, global positioning system (GPS) and magnetometers, ESC takes command from the FC, draws power from the battery and controls the speed of the motors. ESC comes in two varieties: individual ones for each motor or the 4-in-1 ESC which is a single circuit board with four speed controllers built into it. FPV drones usually employ brushless motors for powering their flight, while propellers provide the thrust needed to lift the drone off the ground. FPV drones can have three, four and six propellers too. Finally, the radio and receiver takes the command from the user’s radio controller and relays it to the FC through a specific set of transmission protocols. Power SystemThis consists of the battery and the power distribution board (PDB). FPV drones mostly use lithium polymer batteries and these define the amount of time the drone can remain airborne. PDB is a traditional circuit board which powers the motors but these days many flight controls come equipped with an integrated PDB. FPV SystemThe FPV system contains a camera (or two if the user also wants to record a video), VTX module and goggles. One of the most unique things about the FPV cameras is that the main camera being used to ‘sense’ the surroundings is kept still and mounted at an elevation so that the user can see ahead. Unlike regular drones, there is no gimbal for horizontally or vertically panning the camera. The VTX module converts the captured image/video by the camera into a compatible signal for transmission. Russian Use of FPV DronesRussian design and deployment of FPV drones has followed two near parallel paths: private entrepreneurship and state-supported initiatives. The Russian forces have used FPV drones in both manual and AI-enabled modes and have continuously tested these platforms directly on the battlefield. Drone development efforts are spearheaded by volunteer communities in the country that have a significant academic and hi-tech background. Initially ceding territory to the Ukrainians at the start of the conflict in 2022, Russia has clawed back its advantage on the back of rapid prototyping and scaling in late 2023 and 2024, focusing on two platforms: AI-enabled and manual FPV drones10 and light weight quadcopters11 , the former for kinetic one-way missions and the latter for ISR. The former’s development is an outgrowth of the proliferation of commercially available off-the-shelf (COTS) equipment available in the open market. Another reason is the relative ease of bypassing sanctions on non-military commercial products.12 AI-enabled FPV drones are the next step in the evolution of these platforms. The additional advantage of having a human ‘on the loop’ always remains. The success of these AI-enabled drones was witnessed in a racing competition held at the University of Zurich between 5 and 13 June 2022 when Swift, an AI-enabled FPV drone designed by researchers at the university, went head on against three drone racing world champions and beat all of them.13 The drone used reinforcement learning to train itself from real-time data collected by an onboard camera and an inertial measurement unit measuring acceleration and speed. This process had limitations of the drone not being able to replicate the same performance with changed ambience settings such as change in weather or light patterns. A similar technique seems to have been used by Russian volunteers in August 2023 when they unveiled the Ovod (Gadfly) FPV drone whose onboard AI allowed for attacking static and dynamic targets with up to 90 per cent accuracy.14 Some Russian media outlets have hinted that these drones have already been deployed in battle, mostly by irregulars of the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR), in addition to the Wagner group.15 A critical reason for the use of AI-enabled drones is to remove the drone pilot from harm’s way since use of FPV drones requires the pilot to be in close vicinity of the target. These drones rely on line of sight communication with either the ground station or the radio controller with the soldier. Use of AI-enabled drones aims to preserve the lives of the pilots. FPV drones are being increasingly adopted by Russian forces. An unofficial norm is to use Lancet for long range, kamikaze drones for operational depth and FPV drones for tactical strikes. One of the major advantages (or disadvantages depending on perspective) is that a majority of FPV drones are being procured by and innovated by volunteers and private groups, enabling much better adoption and innovative material scrounging.16 A typical example is that of the Sudoplatov ‘Judgment Day’ group which has created an FPV drone worth US$ 440 and which can carry a payload of seven pounds over almost eight kilometres.17 Other groups include Archangel18 and models like Ghoul.19 Training for FPV pilots has been reduced from four to two weeks while drone racing may be included as an official Russian sport, part of the Games of the Future event this year.20 However, slow procurement efforts by the Russian Ministry of Defence (MoD), as of date, may dampen these efforts in the medium to long term since production scaling will require capital investment in terms of machinery and money. Ukrainian Use of FPV DronesUkraine has been a pioneer of drone warfare in this conflict from the start. Ukraine initially relied on larger drones, but shifted to smaller technology to adapt to Russian advances. This was a progressive step based on Russia ’s increasing control of the airspace. In the initial days of the conflict, when Russia ’s air defense and electronic warfare (EW) capabilities were less pronounced, Ukraine relied on larger drones such as the Turkish TB2 Bayraktar to great effect.21 Ukrainians have also gained from US transfers of tactical micro drones and loitering munitions such as Switchblade, Puma and Phoenix Ghost.22 FPV drones were first introduced by the Ukrainians in end of July 2022 when a video uploaded on X (previously Twitter) by Ukraine’s 93rd Brigade showed an FPV drone taking out Russian soldiers by precisely striking through an open doorway.23 Today, companies like Escadrone have developed Pegasus FPV drones which take five minutes to be assembled and deployed.24 The drone has gone through multiple iterations in design optimisation (improvements in motors, radio antennas and control electronics) since the different variants can be sent to the same target in case of failure, being produced at the rate of 1,000 per month currently. Other groups include Vyriy Drone (Molfar FPV), Aerorozvidka and Drones for Ukraine.25 Ukraine has also attempted using AI-enabled FPV drones to target Russian trenches and troop positions.26 One of the main challenges for Ukrainian drone pilots has been the deployment of extensive electronic warfare (EW) suites and air defence (AD) systems by Russia, as a result of which they were losing close to 10,000 unmanned systems a month. In previous attempts, while a significant number of their FPV drones did get close enough to trenches and Russian armour to inflict damage, there have been ample sightings and reports that suggest that electronic interference has prevented the pilot from observing and therefore precisely homing in on their target as a consequence of the link between the drone and pilot rupturing. Use of AI on board these drones may enable them to continue on an autonomous mode even after communication between the pilot and the drone breaks down. A Ukrainian company, Twist Robotics, is at the helm of creating these drones, which have been termed the ‘poor man’s Javelin’.27 Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has announced the creation of an Unmanned Systems Forces that will bring all drones operated by the country ’s armed forces under a single centralised command. Ukraine aims to produce one million First Person View (FPV) drones in 2024 and the BRAVE1 defence technology cluster is at the forefront of this effort.28 Pilot training has also been expedited at the Boryviter Military School whose primary goal is to enhance the qualifications of Ukrainian service members, focusing on intensive training in eight crucial areas, including UAVs and military communications.29 Quantity as Quality: A Shift in Warfighting PerspectiveFive attributes need to be kept in mind when analysing FPV drones from a quality versus quantity perspective. Cost Benefit AnalysisOne of the major aims within any conflict is to attain a desired military end state with minimal damage and expenditure of own platforms and ammunition. The ongoing conflict in Ukraine, American expenditure of Tomahawk missiles against the Houthis in the Red Sea30 and Israeli strikes in Gaza have renewed urgency across countries on the need for massive quantities of ammunition. The requirement of different calibres along with requirements of precision, combined with limited production capabilities of industrial complexes and exorbitant costs of the ammunition themselves mean that cheaper, faster and scalable alternatives need to be found. FPV drones offer one such alternative. Capable of being produced in their thousands, these drones offer a cheaper and scalable alternative to precision weapons since they combine personalised target selection, accuracy, autonomy, EW resistance and guidance into a single platform, at the fraction of the cost of bigger and more sophisticated platforms. One of the major challenges faced by both countries’ forces has been the syncing between volunteer efforts innovating effective and new designs and the capital expenditure of the governments. Once these are in place, these drones offer far better alternatives to their costlier counterparts and can be seen to offset certain shortfalls in various forms of ammunition including artillery shells, short range tactical missiles and PGMs. Even the US Department of Defense (DoD) has realised the advantages of having thousands of autonomous systems across multiple domains, and announced the Replicator Initiative in August 2023. The aim is to produce ‘attritable’ platforms which are unmanned and are built affordably by August 2025.31 However, though cost is a significant factor in this programme, the aim of the Pentagon is to reduce the cost per piece of an unmanned system from tens of millions of dollars to tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars per piece. Currently, the Switchblade 600 kamikaze drone is likely to be the first platform to be selected under the initiative.32 CollaborationFPV drones are currently used in standalone modes for tactical level actions. But they may be required to act in coordination with other platforms such as other bigger UAVs, artillery batteries and as part of a combined arms assault. FPV drones may also be used in CI/CT areas as part of what this author terms a ‘disaggregated mothership mode’ (DMM) where a larger UAV/ quadcopter can hover over a particular area in a mountainous, forested or built up terrain, register the coordinates and then send them to an FPV operator who can then use the FPV drone for taking out hostile individuals without causing any collateral damage. Another example can be that of AI-enabled FPV drones acting in tandem with drone swarms for taking out adversary counter drone, AD systems while the swarm targets the bigger installation. The requirement of collaboration will require compatible communication systems, all mapped to a certain plug and play command and control architecture, where decentralised teams can cause extensive damage. Scaling and Government SupportThe effectiveness of FPV drones as a major attack platform took a significant amount of time to register in the higher echelons of the Russian military hierarchy as compared to the Ukrainians, because for the latter, innovation exists as a complement to aid. Bigger conventional militaries consider attritable platforms as a sideshow as compared to armour, fighter jets or artillery. However, once the Russian soldiers realised the efficacy and, more importantly, the constant availability and readiness of FPV drones, the Russian MoD has slowly started providing financial support to selected drone makers and help them to scale.33 State support is absolutely essential in scaling up the production line of FPV drones. Platforms like FPV drones will have to demonstrate their effectiveness as kinetic platforms in the battlefield before being considered worthy of being supported through the national treasury. One of the biggest reasons behind this is that the entire concept of an FPV drone is anathema to a conventional warfighter. Most consider ‘rigged’ drones to be worthy of being used only by non-state actors due to their cheap costs and COTS components. Pilot training and Push for InnovationThe cheap cost of FPV drones is offset by the amount of training and hand-eye coordination required to operate them. Even when used in drone racing, the constraint of a look-ahead camera with a narrow field of view requires constant practice to overcome. It is for this reason that the Ukraine Army trains their FPV pilots for a month with a pass rate of only 60–70 per cent, as compared to the Russians’ two weeks training. Iterative Deployment and DesignDeployment of FPV drones has preceded design in an iterative fashion. Stress testing of these platforms has not been done in a lab or firing range but directly on the battlefield which tests the equipment in the conditions it is meant to be used and not on idealised representations. In a number of cases, the design and structure of the FPV drones has undergone a major change based on inputs from users and battlefield footage. ConclusionFPV drones, combined with AI, are the next evolution in warfare. Cheap to design and develop, comparatively easy to scale, these drones have proven that quantity has a quality of its own, at least in future warfare where rates of ammunition expenditure, especially precision ones, may determine the outcome of a war. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Strategic Technologies | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV), Artificial Intelligence | system/files/thumb_image/2015/drone-fpv-t.jpg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Antarctica: The Icy Continent and Indian Engagements | February 23, 2024 | Manoranjan Srivastava |

SummaryIndia has two operational research stations in the Antarctica (Maitri and Bharati) and has till date successfully conducted 42 annual scientific expeditions. India has always considered Antarctica to be a continent of peace and science. Indian Antarctic Bill 2022 provides regulatory framework and legal mechanisms for India’s Antarctic activities. IntroductionAntarctica is key to our understanding of earth’s climate and ocean systems. Antarctica is world’s natural laboratory and its pristine environment is a natural tracker of global climate change for over millions of years. The unforgiving climatic conditions, freezing temperatures, frequent blizzards, chill factor induced by windy weather are some of the factors which makes Antarctica an inhospitable continent with no permanent population. Since the first half of 20th century, Antarctica has been a part of international geopolitics. The urge for democratisation and universal participation by some nations have however amicably co-existed along with scientific endeavours such as conventions for conservation of marine species and unprecedented international cooperation. The precondition that Antarctica shall be used for peaceful purposes only, prohibition of nuclear explosions and firm regulation regarding demilitarisation have prevented Antarctica from becoming a place of international discord. Antarctica is administered by the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) 1959 which entered into force on 23 June 1961. India’s interest and commitment to Antarctic studies dates back to 1981, when first Indian expedition to Antarctica was launched from the shores of Goa. Today, India has two operational research stations in the Antarctica (Maitri and Bharati) and has till date successfully conducted 42 annual scientific expeditions to Antarctica. India’s continuous and growing presence in Antarctica is in accordance with its commitment to science and protection of fragile Antarctic ecosystems. The White ContinentAntarctica, ‘the White continent’, is the fifth largest continent and is often referred to as the coldest, windiest, driest and highest continent. The area of this vast wilderness is around 14 million sq km in summer1 and swells to twice of its original size during winters. The frozen continent is a silent witness to many secrets and stories of past climatic conditions of the earth, global warming and drifting continents. The stormy Southern Ocean around Antarctica and its harsh climatic conditions with howling blizzards makes it an isolated continent. The Transantarctic Mountain splits the continent into East and West Antarctica. The East or Greater Antarctica comprises two-thirds of the total area. The continent is also a huge reservoir, holding 75 per cent of earth’s fresh water,2 an asset, which has already fuelled human imagination for its exploitation, should need arise in the future. Classified as a desert in technical terms based on annual precipitation in the form of snow averaging less than 50 mm a year, Antarctica is placed in Hyper Arid category along with great deserts like Sahara and Atacama.3 The continent with an average elevation of around 2,200 m contains nearly 29 million cubic km of ice and is often battered by colossal blizzards with winds touching up to 320 km per hour.4 India in AntarcticaIndia’s tryst with Antarctica began in December 1981 with the launching of the first expedition from the shores of Goa, a programme crafted carefully by the newly formed Department of Ocean Development.5 The 21-member team under the leadership of Dr S.Z. Qasim, embarked MV Polar Circle, a chartered ship from Norway, for the first Indian expedition to Antarctica. The arduous voyage of 77 days covered a distance of nearly 21,366 km6 with a brief stop at Mauritius for logistics requirements. The expedition unleashed India’s scientific ambitions and aspirations. The headline "Indians quietly invade Antarctica" in the New Scientist magazine said it all, as New Delhi till then was not a signatory to the Antarctic Treaty of 1959. India’s involvement in the scientific pursuits at Antarctica dates back to an agreement with the Soviet Union for joint upper atmosphere exploration from the Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station (TERLS), Thiruvananthapuram and the Soviet Antarctic Station, Molodezhnaya. Shri Parmjit Singh Sehra, a scientist at Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad, participated in the 17th Soviet Antarctic Expedition in 1971 under the agreement.7 ‘Dakshin Gangotri’, the first Indian Scientific Research Station was commissioned in 1983–84 enabling first wintering by Indian team in Antarctica.8 The station was subsequently decommissioned on 25 February 1990.9 Subsequent expeditions nurtured India’s drive to engage Antarctica in more intensive scientific terms. The need for a bigger and better equipped station was felt, which led to the construction of MAITRI, the second Indian station on Schirmacher Oasis, Antarctica in 1988. The station can support around 25 people in the main structure and has in addition containerised living modules for the summer members. Lake Priyadarshini, apart from enhancing beauty of Maitri, is the life line catering to the water needs of the station.10 India since then has gained rich polar experience due to its continuous scientific engagements in Antarctica. The yearning and appetite for an even bigger role in polar affairs made her look for a more strategic location to have yet another station which would eventually catapult her status to the elite group of countries who have multiple stations. It was first week of February 2005 and sea around Larsmann Hill had just started showing the signs of freezing when a specially selected five-member team (including the author of this article) from ongoing 24th scientific research expedition landed at Larsemann Hill site and initiated scientific studies with limited logistics support. The site subsequently was found suitable and approved by the Government of India for construction of station Bharati, which is the third and state-of-the-art station located at Larsmann Hill, between Thala Fjord and Quilty bay, east of Stornes Peninsula in Antarctica. It is about 3,000 km east of Maitri and has the capacity for 72 personnel including 25 in emergency shelters/summer camps in summers.11 The Indian Antarctic science programme is rich as well as diverse. It consists of studies in areas such as Atmospheric sciences, Biological sciences, Earth sciences and Glaciology, Human physiology and Medicine, etc. Ice core drilling and lake sediment core has long remained a focused area for Indian scientists for their urge to traverse through paleo climatic history of this icy continent. The ice core analysis from Central Dronning Maud Land have suggested temperature variations in East Antarctica and exhibited its close relation with Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) and El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO). The Indian Biological Science institutes have made significant contribution in microbiological research and have identified around 32 new species of bacteria in Antarctica. The seismological observations and monitoring of seismicity in and around Antarctica is being carried out by establishing permanent Seismological Observatory and high-resolution maps have been published as Special Series Map on Schirmacher Oasis and Larsemann Hills. In the era of scientific collaboration and cooperation, promoting opportunities to undertake joint programmes and multidisciplinary scientific studies in complex areas such as identification and study of high-energy neutrino originating within our galaxy and beyond, studies of subglacial lakes, studies related to meteorites, etc., needs to be encouraged.12 Exchange visits of Indian scientists to other stations and laboratories such as the South Pole Telescope and Ice Cube Neutrino Observatory will enhance scientific temperament and also help in building bridges of friendship and long-term cooperation. India’s Geostrategic Engagements in AntarcticaIndia has always considered Antarctica to be a continent of peace and science. India’s stance since the beginning has been to realise an international agreement on development of Antarctica’s resources for peaceful purposes. Ambassador Arthur S. Lall, India’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations had on 19 February 1956 requested that the question of Antarctica be included in the provisional agenda of the United Nations General Assembly. India’s memorandum stated that

India once again in 1958 presented a memorandum and requested that the Question of Antarctica be included in the agenda of 13th regular session of the General Assembly.13 India was however persuaded to withdraw its move as the preparatory meetings for the Antarctic Treaty had already commenced by then. India has always pronounced the philosophy of considering Antarctica to be a Common Heritage of Mankind and has not acknowledged Antarctic territorial claims. It has in all earnestness endeavoured that Antarctica remains a continent of peace and science. India, however, has remained cognizant of the growing international interest in the Antarctica, be it the Convention on Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) at Canberra in May 1980, the deliberations on exploration and exploitation of Antarctic mineral, the apprehensions of non-aligned nations on exclusivity of the ATCP membership or the implications of UNCLOS in Antarctica. India took active plunge in the Antarctic activities by sending its first scientific expedition to Antarctica in 1981. The second expedition went next year in 1982 and returned in 1983. Buoyed by two successive scientific expeditions, India felt that its role and active engagements in Antarctica cannot be deferred any further. It realised that a meaningful Antarctic engagement in the strategic matters having international bearing was difficult to be done being outside of ATS framework, hence it decided to join Antarctic Treaty System. India signed Antarctic Treaty on 19 August 1983 and received the consultative status on 12 September 1983 .14 On 26 December 1983, the third Indian expedition arrived in Antarctica and the first Indian station ‘Dakshin Gangotri’ was set up by the team in a record 60 days. The record remains unbroken even after four decades as no country has built a permanent station in Antarctica in one Antarctic summer and has thereafter wintered there.15 India joined the Scientific Committee of Antarctica Research (SCAR) on 1 October 198416 and the Protocol on Environmental Protection (Madrid Protocol) to the Antarctic Treaty, also known as the Environmental Protocol, came into force from 14 January 1998. India is also a permanent member of the Commission for Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) since it ratified the convention on 17 June 1985 and a member of Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programme (COMNAP).17 India has since 1981 continuously sent its scientific expeditions every year to Antarctica. In 2021, India supported the cause of sustainability in protecting the Antarctic environment and for the first time offered to co-sponsor the proposal to designate East Antarctica and the Weddell Sea as the Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) along with Australia, Norway, Uruguay and the United Kingdom to the CCAMLR.18 The support and co-sponsoring is aligned to the principles of conservation and sustainability under the larger framework of global cooperation such as Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and UN Decade of Oceans. More recently, the Indian Parliament passed the Indian Antarctic Bill 2022 in pursuant to India’s accord to the Antarctic Treaty, Madrid Protocol and CCAMLR. The landmark bill provides regulatory framework and legal mechanisms for India’s Antarctic activities. The bill also shall help in providing enhanced international visibility and credibility in polar governance. The bill proposes setting up an apex body, the Indian Antarctic Authority (IAA) under the Ministry of Earth Sciences to facilitate programmes and activities permitted under the bill. Since joining the Antarctic Treaty, India for the first time conducted the 30th Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM) and the 10th meeting of the Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP) in April–May 2007.19 As per the Article IX of the Antarctic Treaty, the ATCM is held every year (Prior to 1994, the ATCM was held every two years).20 In the ATCM and CEP meetings, the original 12 Parties to the Treaty and the Consultative Parties meet

The meeting comprises representatives from the Consultative Parties, the Non-Consultative Parties, and Observers such as SCAR, CCAMLR and COMNAP and invited experts such as the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC) and the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO).21 At the ATCM, the Measures, Decisions and Resolutions adopted by consensus give effect to the principles of the Antarctic Treaty and the Environment Protocol and provide regulations and guidelines for the management of the Antarctic Treaty area and the work of the ATCM. The present decade has marked significant milestones in India’s global leadership role. India assumed the rotating Chairmanship of Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) on 16 September 2022 and under its first-ever Chairmanship, successfully conducted the 23rd SCO Summit 2023. India also assumed the presidency of the G20 forum on 1 December 2022 for the first time and successfully conducted the G 20 Leaders’ Summit on 9–10 September 2023. In 2024, the 46th ATCM and the 26th meeting of the CEP is slotted to be held in India from 20 to 30 May22 which once again ascertains India’s enhanced stature and role in the realm of Antarctic science. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Terrorism & Internal Security | Antartica, India | system/files/thumb_image/2015/maitri-antartica-t.jpg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pakistan Elections 2024: ‘Same Politics’ and Some New Trends | February 23, 2024 | Smruti S. Pattanaik, Nazir Ahmad Mir |

SummaryDespite efforts by the country’s powerful army to weaken the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) led by former Prime Minister Imran Khan, independent candidates supported by the PTI secured the highest number of seats in the national assembly. The coalition government led by Shehbaz Sharif has its task cut out to deal with Pakistan’s economic and security challenges. Pakistan’s 12th national and provincial elections were held on 8 February 2024, amid a tough political, economic and security situation. Many politicians, commentators and international observers remained skeptical till the last moment about whether the elections would be held as scheduled. The date itself was set only after the intervention from the top court of the country, asking the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) to come up with a date for elections to end the uncertainty surrounding it.1 The assemblies had completed their terms and were dissolved in August 2023. According to the constitution of Pakistan, the elections have to be held within three months after the dissolution of the assemblies. However, delimitation of constituencies according to latest census figure took some time. Finally, amid tough security measures in which the army and civil armed forces were deployed to provide security to the polling stations and the voters,2 voting for the national and provincial assemblies was held on the same day across the country. Overall 47.6 per cent polling was recorded in the elections.3 Out of a total 128,585,760 voters in Pakistan, over 48 per cent of them cast their vote. The percentage of voting was marginally less than in 2018, which stood at 52.1 per cent. Compared to the last election, however, more people cast their votes as the number of total registered voters increased from 106 million in 2018 to 128.6 million in 2024. Almost all Pakistan observers and seasoned political pundits were proven wrong as soon as the final results started pouring in. Despite all the efforts by the country’s powerful army, known as the establishment, to weaken Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) led by the former Prime Minister Imran Khan, independent candidates supported by the party secured the highest number of seats in the national assembly. It also got overwhelming majority in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and came close second in the crucial province of Punjab (see Table I and Table II). Prior to the election, it was speculated that Nawaz Sharif, and his party, the Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N), favoured by the establishment, might win most seats, if not the majority in the national assembly. Also, survey conducted by Gallup Pakistan one month before the elections showed that the gap between the PTI and PML-N was decreasing consistently since March 2023 as the election were inching closer.4 In Punjab, while 34 per cent said they would vote for the PTI, 32 per cent were going to vote for the PML-N. At the national level as well, though Imran Khan was leading, the gap between the PTI and PML-N was getting bridged as the elections were coming closer. On the Election Day, the voters gave a different mandate, proving all speculations wrong. It is also true that the National Assembly mandate was fractured with no party getting a clear majority. Table I: Seats Won by Parties in 2024 and 2018 Elections

Source: Geo TV National Election Results 2024 & Dawn News 2018. Context of 2024 ElectionsThe elections were held in the background of the 9 May 2023 protests, against the arrest of the former Prime Minister Imran Khan and deteriorating economic and security situation. Khan’s government was removed from power through a no-confidence motion in April 2022, moved by the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM), an alliance comprising over a dozen parties. After Khan’s fall, the PDM formed the government led by Shehbaz Sharif as the Prime Minister. However, the deteriorating economic situation and security conditions in the country took the wind out of the ruling alliance’s sails. Since his ouster, Imran has been accusing the West for conspiring to remove him from power. He also alleged that he was a victim of the political conspiracy by the PDM with the support of the establishment. The fall-out with the establishment came when Khan differed on the appointment of next Army Chief Asif Munir whom he had removed as Director General of ISI in 2017 and replaced him with an officer seen as close to him, Lt Gen Faiz Hamid. After his removal from power, the establishment filed several cases against him for revealing state secrets in the Cipher case, Toshakhana corruption, instigating violence, among others. Violent protest erupted after Khan was arrested by Pakistan Rangers from the Islamabad High Court premises. Military installation and the house of Lahore Corp Commander was attacked and vandalised by his supporters. Though Imran condemned these violent incidents, the damage was already done. Several senior party members left PTI in the aftermath of this violence. Moreover, these attacks were a severe blow to image of the invincible powerful Army who have stitched coalitions at their will and governed through a hybrid system. Roadblocks to PTI’s ComebackIt is true that Imran Khan’s popularity was low when he was voted out of power. The economy was in shambles. His decision not to approach the IMF for funds was pinching the economy, inflation was peaking, fuel and prices of essential commodities were rising. Yet Khan was seen as anti-corruption crusader. He did not hesitate to put his political opponents behind the bars. Yet, once he was out of power, he skillfully changed the narrative of Western conspiracy against him, military interference and painted his opponents as ‘corrupt politicians’ in cahoots with the establishment. His narrative appealed to the new generation of young voters who resent Army’s interference in the politics. Since his ouster, all efforts were made by the establishment to decimate Imran Khan, his party and weaken his support base by arrests, filing false cases, coercing his party members to change loyalty. Khan has not yielded so far and has been demanding a fair trial of the cases against him and his party members. He has also demanded a fair investigation of the 9 May incidents. While in Nawaz Sharif’s case, Pakistani court quashed corruption charges against him and freed him, in the cases against Imran Khan, judgements were rushed to convict him just before the elections. In two weeks, he was punished in three cases and sentenced to 10, 14 and seven years in prison.5 The ban on Nawaz Sharif to contest election was lifted as the court said a ban for life to contest is a violation of fundamental rights of a citizen. Nawaz Sharif returned from self-imposed exile after almost four years. Within two months, all cases against him were cleared so that he could file nomination for the elections.6 His party was allowed to run an enthusiastic election campaign, unlike the PTI whose election symbol, bat, was taken away just few weeks ahead of the elections.7 Khan’s party was barred from fighting elections as a registered political party. Even its independent members were often stopped from campaigning and their rallies were raided by the police.8 The economic and security situation in Pakistan has been deteriorating due to the persistent political instability and confrontational politics. The country’s economy has been growing at a rate of 2–3 per cent,9 much lower than the country needs to grow to effectively address its economic issues. Foreign investment has dwindled and foreign exchange reserve touched a little more than US$ 4 billion sending alarm bells. There was a stampede for food in Sindh.10 Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC) was established as a single window clearance and Pakistan Investment Policy (PIP) 2023 was adopted in July 2023. In 2022, Foreign Direct Investment stood at US$ 1.5 billion. The IMF preconditions to lift subsidy to enable Pakistan to receive the IMF tranche only contributed to economic hardship. Similarly, the country is facing increasing security challenges.11 The elections were held in this background, with the expectation that the new government would address these challenges. People’s VerdictThe electorate in Pakistan have given a fragmented mandate in the 2024 elections. No single party has won the majority in the national assembly as well as in the provincial assemblies of Punjab and Balochistan. In Sindh, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) has got a clear majority and in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KP), the PTI supported independent candidates have won an overwhelming number of seats. Elections for one national assembly seat was postponed due to the killing of a candidate in KP.12 The result for another seat was withheld due to the reports of rigging. Out of the 264 declared results for the national assembly seats, the PTI-backed candidates have won 93 seats, PML-N 75, PPP 54, and Mutahidda Quami Movement-Pakistan (MQM-P) has won 17 seats. No party, thus, has been able to get close to the halfway mark of 134 to form the government. New parties, formed by the former PTI members like the Istahkam-e-Pakistan Party (IPP) Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf Party-Parliamentarian (PTI-P) performed badly. Some parties have alleged rigging and distorting of the election results as the declaration of results were inordinately delayed. The most explosive revelation was made by Rawalpindi Commissioner Liaquat Ali Chattha who accused the government of rigging the election by making independent candidate lose the election.13 This has added to the rising chorus of rigging. This is also not the first time Khan is accusing the government of rigging. He had done that in 2013 and an independent commission had rejected his accusation as baseless. The low turnout may have helped the PTI win the highest number of seats in the national assembly. One factor may be that young voters who remain both tech-savvy and active on social media helped the PTI as the party remains popular among the young. The PTI, left with no option but to explore new ways to mobilise its voters due to the restriction imposed on its activities, used ‘guerilla campaign’, entailing the use of social media to hold meetings, rallies and convey the party’s messages to the voters.14 This could have helped to woo young voters particularly who see Khan’s conviction as politically motivated and his ouster in April 2022 as a bigger conspiracy. Khan who was a popular cricketer is also seen as an uncorrupt politician who had sold the dream of ‘Naya Pakistan’ which was cut short by the establishment. Since the 2018 elections, 10.42 million new voters were added to the total number of voters in the country. More importantly, 56.86 million are young voters15 , aged between the age of 18 and 35. Though there is no survey to show how many and how these young voters voted, given the PTI’s outreach on social media, its young supporters may have come out to vote for the party-backed candidates. According to Dawn, in 2018, total 46.89 per cent female voter turned out to vote. In 2024, female voters share decreased to 41.3 per cent. The report further notes that “Men’s turnout increased from 56.01pc to 58.7pc. Approximately 2 million ballot papers were excluded from the count across all 264 National Assembly (NA) seats contested which surpasses victory margin.”16 Table II: Seats Won by Parties in Provincial Assemblies

Source: Geo TV Election Results 2024 Challenges AheadPakistan faces the same challenges that it has been facing, particularly for the past over two years. These include political (in) stability, economic crisis, and emerging security threats from terror groups in the country. Elections 2024 have not settled the political confrontation among the political rivals in the country. If anything, the election results have intensified it. While the PTI and PML-N both claimed victory in the elections, parties like Jamaat Ulema Islam-Fazl (JUI-F), Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) along with the PTI have claimed that the elections were rigged. This has re-energised the claims questioning the credibility of the elections. There are slogans like ‘mandate thieves’ and demand for return of ‘85 seats’ that were snatched away from the PTI.17 The fractured mandate means that the political parties need to cobble together a coalition government in the spirit of give and take. The PTI, PML-N and PPP fought the elections less on issues related to common people, and campaigned against each other. The Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) that formed the government under Shehbaz Sharif was dismantled prior to the election given the divergent views among the partners. In many constituencies, these political parties fought closely. These differences were proven when the PPP initially decided to offer support to the PTI than PML-N. The PTI however refused to partner either with the PML-N, PPP or even MQM-P. Given the current circumstances, the fractured mandate has pushed the PML-N, PPP and MQM-P along with other smaller parties together to get engaged in intense discussion. The parties have to come together as 29 February will be the first day for the National Assembly to convene. Once the coalition government is formed, it essentially will be weak for a few reasons. First, instead of Nawaz Sharif, who was expected to be the next Prime Minister, Shehbaz Sharif has been appointed as the leader of the new alliance. Given the performance of Shehbaz Sharif during the stint of 16 months as prime minister from April 2022 to August 2023, he may not have much to offer to address the economic crisis as the IMF’s tough conditionalities would be difficult to ignore. Additionally, he may remain hostage to the alliance partners and may not be able to take strong decisions. The country is facing a serious economic crisis. There has been no sign of it recovering, despite all the bailouts from the IMF and aid from other countries.18 The imports are increasing and exports are decreasing. The Pakistan economy has contracted for the first time.19 Each party has made big promises and claims, like creating millions of jobs, controlling inflation, or rolling out welfare schemes.20 Managing the economy is going to be a tough challenge amidst the increasing pressure from the IMF to curb government expenditures, expand tax net and remove subsidies. The debt burden has also increased and debt servicing would paralyse the economy. Yet another challenge for the new government will be dealing with the emerging security challenges. In the last couple of years, not only have the terror attacks increased manifold, but Pakistan’s relations with Afghanistan have deteriorated. One of reasons given by some observers about the possibility of the postponement of the elections was the increasing security concerns in Balochistan and KP particularly. Overall, terror attacks have increased by 70 per cent in 2023.21 The low voter turnout in these two provinces (39.5 per cent in KP and 42.9 per cent in Balochistan), was due to the security threats. The elections for the one national assembly seat in KP were cancelled due to the killing of one of the candidates. ImplicationsThe fractured mandate will make the government unstable and would be easy for the establishment to manipulate as one had witnessed during the previous regimes in Pakistan. The government has to work closely with the military for its own political survival. The PML-N and PPP had once agreed to a charter of democracy with an agreement to keep the Army out of politics. Though this understanding was violated by Benazir Bhutto when she had a deal with General Musharraf, the two parties cannot be expected to revive this understanding. It is likely that the PTI and now JUI-F, who has rejected the election results,22 will try to create hurdles in the functioning of the government. Shehbaz Sharif will be busy keeping the alliance together, impacting the tough decision-making that the country needs on the economic and security front. Many within Pakistan and outside countries expected a politically stable Pakistan as that would make it easy to deal with numerous challenges it faces. However, the fragmented mandate has created political uncertainty. Many predict that the new government may not complete the term. The weak government may not be able to come up with a united policy to deal with the threat of terrorism. Internal priorities of the new government will impact its foreign policy decision-making, whether with the United States, China, Afghanistan and India. In the worst of the cases, the country may return to severe political instability if the new government will not be able to not hold its allies together. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

South Asia | Pakistan Politics, Pakistan, Elections | system/files/thumb_image/2015/pakistan-politics-t.jpg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bhutan’s 2024 National Elections: New Dawn with an Old Guard | February 21, 2024 | Sneha M |

SummaryThe People’s Democratic Party (PDP), under the leadership of Tshering Tobgay, clinched victory in the Bhutan National Assembly elections by securing 30 out of 47 seats. The electoral process unfolded in the backdrop of economic distress faced by the people in Bhutan. The PDP government’s key tasks going forward include revitalising the economy and navigating Bhutan’s relationship with India and China. Almost all South Asian countries embraced multiparty democracy in 2008, with Bhutan and Maldives holding elections with multiple parties for the first time that year. This is not to say that democracy has had a smooth run in the region ever since. Bhutan, one of the latest entrants to democratic political system, though has demonstrated considerable enthusiasm to continue with peaceful democratic transition from one election to another, while elections in many other states like Sri Lanka, Maldives and Pakistan have led to controversies and political instability. The 2023–24 National Assembly (NA) elections in Bhutan underscored this commitment, serving as a testament to the consolidation of democratic principles in Bhutan’s political landscape. A new leadership has assumed office following the conclusion of the fourth general elections held in two rounds on 30 November 2023 and 9 January 2024. The election was predominantly influenced by significant economic challenges such as high job attrition rates, skyrocketing brain-drain and infrastructure development that have prompted people to critique the longstanding policy of the Bhutanese political system prioritising ‘Gross National Happiness’ (GNH) over economic growth. The Electoral ProcessAs per the 2008 Election Act of the Kingdom of Bhutan, the National Assembly elections are held in two rounds (Section 189).1 In the primary round, all registered political parties are eligible to participate, while the top two parties by vote count proceed to the final round, which is called the general election. In the fourth national elections, all five political parties listed below participated in the primary round, which saw the exit of Druk Phensum Tshongpa (DPT), Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa (DNT), the former ruling party, and Druk Thendrel Tshogpa (DTT), a relatively new entrant. In the subsequent final round, the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), under the leadership of Tshering Tobgay, clinched victory by securing 30 out of 47 seats in the National Assembly.2 The Bhutan Tendrel Party (BTP), registered only in January 2023, and led by Pema Chewang, a former civil servant, secured the remaining 17 seats, becoming the primary opposition party. The overall voter turnout was recorded at 65.6 per cent.3