You are here

| Title | Date | Date Unique | Author | Body | Research Area | Topics | Thumb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDF’s Subterranean Challenge: Profiling Gaza Metro, Hamas’s Centre of Gravity | December 28, 2023 | Rajneesh Singh |

SummaryThe subterranean infrastructure developed by Hamas, popularly known as the ‘Gaza Metro’ consists of tunnels, command and control centres, living spaces, stores and contingency fighting positions. The infrastructure is the pivot of Hamas’s irregular warfare strategy and allows it to undertake both offensive and defensive operations and has been assessed as one of its centres of gravity. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) has been aware of the infrastructure but has possibly been surprised by the scale and sophistication achieved by Hamas in tunnel construction. The IDF’s technologies and doctrinal concepts are being tested every day in the ongoing war and will have a number of lessons for the Indian Army. Hamas has developed a complex subterranean infrastructure consisting of tunnels, command and control centres, living accommodation, stores and contingency fighting positions. The tunnels also have designated spaces for rocket-assembly lines, explosive stores, and warhead fabrication workshops.1 This infrastructure is famously known as the ‘Gaza Metro’. The Metro is reinforced by concrete and other building material and protected by blast doors, improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and booby traps. The tunnels have been in use since at least the early 1980s, and members of various Palestinian insurgent organisations have been known to use them since the first Intifada, beginning in 1987.2 In the aftermath of the 2021 Israel–Hamas conflict, Hamas leader, Yahya Sinwar claimed that Hamas has 500 kilometres of tunnel system and that the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) has damaged only 5 per cent of it.3 There is no way to verify Sinwar’s claim but is indicative of the magnitude of challenge the IDF faces in the ongoing war. Tunnel warfare is not new and dates to the ancient times. Jews used them against Romans in Judea in the first century.4 In the more recent times, the tunnels have been used in the battles of the Vimy Ridge, Messines and Somme of World War I, by the Viet Congs in Vietnam and in Mariupol, Bakhmut, and Soledar during the ongoing war in Ukraine.5 Gaza Metro is more than a just any military infrastructure. It is the centre of gravity (COG) of Hamas’s military wing.6 The Brief also attempts to analyse various aspects of operational significance of Gaza Metro using certain facets of the theoretical construct of COG advanced by Colonel John A. Warden of the US Air Force, Professor Joe Strange and Colonel Richard Iron, and Professor Antulio J. Echevarria II, retired US Army officer. History of Gaza MetroThe tunnels in Gaza predate Hamas. It is believed that they have been in use since the early 1980s7 after the city of Rafah was divided by the new border recognised in the 1979 peace treaty between Egypt and Israel.8 It was initially used by the divided families to communicate among themselves and by smugglers to transport goods. Hamas was raised in 1987 and soon it realised the military importance of the tunnels. It began digging tunnels in the mid-1990s, when Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was granted some degree of self-rule in Gaza by Israel. The group began tunnelling in earnest since 2005, when Israel withdrew from Gaza, and later when Hamas assumed power in 2006 election.9 As per the reports, the tunnels in 1990s were approximately one meter wide and smugglers used winch motors to haul goods along the sandy tunnel floors in hollowed-out petrol barrels.11 Hamas has since gained considerable expertise in tunnelling and construction of underground infrastructure which has advanced security features, sewage disposal and air-conditioning systems, etc. Hamas and Gaza MetroThe Gaza Strip has an approximate area of 365 square kilometres. If Yahya Sinwar’s claim of 2021 of Hamas having built 500 kilometres of tunnel system is true, then it would be equivalent of having 10 parallel north to south tunnel systems and eight parallel interconnecting tunnels running east to west.12 The Gaza Metro is so designed that there may be dozens of shafts leading to a tunnel at depths of between 20 and 80 meters. As per some accounts, the density of tunnels is so high that some crisscross at different depths.13 To create a subterranean system of this magnitude requires a dedicated organisation, high level of technological expertise, and resources in terms of trained manpower, equipment and money. Israeli officials have reported that Mohammad Sinwar, the brother of Yahya Sinwar, is heading the tunnel building project.14 Gaza has been under land, sea and air blockade by Israel and Egypt since 2007 and it was not expected to possess capability or resources to dig such an infrastructure. It was appreciated that Hamas has employed diggers using basic tools, used basic electrical fittings, and diverted concrete meant for civilian and humanitarian purposes towards tunnel building project. However, two of the tunnel systems discovered during the ongoing war, viz. near al Shifa Hospital and other close to the Erez crossing belies this assessment. The details of these tunnels have been discussed later in the Brief. Tunnel under al-Shifa HospitalIn the second week of November 2023, IDF’s 162nd Division was operating in Hamas’s “security quarter” of Gaza City, adjacent to al-Shifa Hospital. The troops of Givati Infantry Brigade reportedly found intelligence materials, weapons manufacturing plants, anti-tank missile launch positions and tunnels.16 On 17 November, the IDF located one of the shafts which led to the entrance of a bigger tunnel. This tunnel led to a blast door leading to a complex which had multiple rooms and one of them “was a spacious bedroom with two large beds and a large modern air conditioning unit, a kitchenette, a bathroom, and other facilities, as well as extensive plumbing and electrical wiring to enable all of the infrastructure”.17 The tunnel shaft leading to the main tunnel was approximately 2 metres high, lined with stones and concrete. The complex under the hospital was reportedly being used by Hamas as a command and control centre.18 Tunnel near Erez CrossingThe IDF reported on 17 December that it had discovered largest tunnel ever—four kilometre long and 50 metres deep—near the Erez crossing. The tunnel reinforced with concrete had electrical fitments and was wide enough to allow a vehicle to pass through. The IDF also released a video of Mohammad Sinwar driving a car through a tunnel. In another video released by the IDF, Hamas fighters were seen using a large drill. In the tunnel near the Erez crossing, the IDF reportedly found “unspecified digging machines” not reported earlier.19 One section of the tunnel was approximately 400 metres from the Israeli border. The IDF has informed that the Combat Engineering Corps’ elite Yahaom unit and Gaza Division’s Northern Brigade used “advanced intelligence and technological means” to uncover the tunnel network.20 Operational Employment of Subterranean InfrastructureThe infrastructure is the pivot of Hamas’s irregular warfare strategy and allows it to undertake both offensive and defensive operations. It offers Hamas asymmetric advantage, negating some of the technological advantages available to the IDF. The fact that Hamas has constructed the subterranean system under one of the world’s densest urban locations complicates the matter further for IDF. The system is designed to withstand IDF’s aerial and ground bombardment. The design and construction enable Hamas to locate its leadership, combat units, headquarters, command and control centres, weapons and supplies inside the complex. It also enables various military echelons to move freely between various prepared contingency positions. Hamas has located power generation and air-conditioning systems, plumbing and sewage disposal arrangements and food supplies within the infrastructure. This is helping its fighters to better withstand the siege laid by the IDF in the ongoing war. The tunnels also allow the fighters to escape the combat zone when they are decisively surrounded by the IDF, as was the case in battle near the al-Shifa Hospital. Hamas fighters are using tunnels to undertake offensive operations by infiltrating behind IDF positions and launching surprise attacks using snipers, rocket propelled grenades (RPGs) and other weapon systems. It enables small teams to appear undetected behind IDF lines, strike and withdraw. Gaza Metro as Centre of GravityClausewitz originated the concept of attacking the enemy’s centre of gravity which he described as “the hub of all power and movement, on which everything depends. That is the point against which all our energies should be directed.”21 A fighting force can have multiple centres of gravity and each centre will have an effect of some kind on the others. Hamas too has multiple centres22 and some analysts have described Gaza Metro as one of them.23 Warden’s Five-Ring ModelWarden has conceptualised “Five-Ring Model” related to COG, of which infrastructure is the third critical ring. The infrastructure relates to enemy's transportation system—that moves civil and military goods and services in the combat zone. Gaza Metro is essential to move troops, warlike stores, command instructions and intelligence around the battlefield and if the IDF can disrupt the movement, Hamas will have lesser ability to resist it. Although Warden agrees with Clausewitz’s description of COG as “the hub of all power and movement”, he goes further to describe it as “that point where the enemy is most vulnerable and the point where an attack will have the best chance of being decisive”.24 Warden’s first ring and the “most critical” ring is the command ring, which refers to the leadership and communication resources.25 It is assessed that Hamas’s leadership,26 including Yahya Sinwar, leader of the Hamas movement within the Gaza Strip, Mohammed Deif, commander-in-chief of the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades, and Marwan Issa, the deputy commander are hiding in the subterranean complex. Neutralisation of Hamas leadership is likely to have a decisive impact on the outcome of war. It is also expected that Hamas leadership would have constructed multiple safe hideouts inside the subterranean infrastructure, from where they can direct their subordinate commanders and units. It is also likely that only the most trusted Hamas members would be aware of these locations. It would require sustained intelligence operations by Israel to generate actionable intelligence. However, once the Hamas leadership is cordoned inside the tunnels, they would be extremely vulnerable to IDF operations. For the moment, the IDF is unaware of the exact location of the leadership and is destroying as much of this subterranean complex, as is possible to cause “strategic paralysis—by destroying one or more of the outer strategic rings or centers of gravity”27 —the infrastructure ring—the Gaza Metro. Strange and Iron’s TheoryThe Strange and Iron’s theory is helpful to identify the location of COG and the impact of operations against it. The theory aligns with the J.J. Graham’s translation of On War, published in 1874 which postulates that: “As a centre of gravity is always situated where the greatest mass of matter is collected, and as a shock against the centre of gravity of a body always produces the greatest effect, and further, as the most effective blow is struck with the centre of gravity of the power used, so it is also in war.”28 Hamas is cognizant of the incredible capability and resources of Mossad and Shin Bet to generate actionable intelligence and doctrinal, technological, and material superiority of the IDF to undertake combat operations. To counter Israel’s operational superiority, Hamas relies on low-tech solution in the form of subterranean infrastructure. The nature of infrastructure provides Hamas inherent physical protection, ease of movement and concealment to command and control elements and, combat, and logistic units. The Gaza Strip is one of the densest urban locations anywhere in the world. Tunnels in conjunction with urban infrastructure helps to create extremely potent defensive localities and killing grounds. The IDF hopes to find the leadership and fighters of the al-Qassam Brigades inside the Gaza Metro. Hamas has claimed that Gaza Metro is spread over 500 kilometres. Hamas is expected to dissipate its forces all along the Metro to avoid presenting a concentrated target to the IDF. However, once located, and fixed, the IDF will be able to neutralise Hamas forces with relative ease inside the tunnel system.

In the context of Gaza Metro, the subterranean nature of the infrastructure reinforced with concrete and other building material and further hardened using Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) and booby traps are the CCs. The camouflage and concealment arrangement to prevent detection of tunnels are the CRs while entry and exit points, ventilation and sewage arrangements, and communication infrastructure to enable command of Hamas fighters are the CVs. Echevarria’s TheoryEchevarria postulates COG is identified to achieve total collapse of the enemy—which is considered both as an effect and an objective.30 He further elaborates on the construct to suggest that the COG helps in identifying “way”—course of action—within an “ends-ways-means” construct to achieve annihilation of the enemy.31 This aspect may not be true when fighting an ideologically motivated and radical organisation like Hamas. It is possible that the IDF may identify and destroy Hamas’s tunnel system and thereby achieve destruction of Hamas’s military leadership and fighting units, however, in all probability the organisation will survive and grow, perhaps even more radical. “Terrorist groups are known to survive the loss of their leaders and members. It is quite likely that even if Israel destroys Hamas’s military wing, the idea of Hamas may survive.”32 IDF’s Tunnel Warfare CapabilityDevelopment of Technological CapabilitiesThe IDF has been aware of Hamas’s underground infrastructure and has been working towards new technologies and doctrinal concepts. When the first tunnel was discovered, the IDF established a laboratory, manned by engineers, physicists, geologists and intelligence operatives under the Gaza Division. The laboratory employed innovative soil research techniques, including scanning and decoding signals, and developed new detection techniques. In 2018, a review of then IDF’s underground combat capability was undertaken and a new training manual was published.33 The Israeli scientists and engineers have developed several new innovations, most of them are classified. The IDF’s specialised units have been equipped with special conical penetrators, drills, robotic systems that can inject special ‘emulsions’ either to seal or destroy the tunnels.34 IDF also makes innovative use of technologies such as ground and aerial sensors, ground penetrating radars, geophones, fibre optics, microphones, special drilling equipment and others. The Israeli scientists have developed radio and navigation equipment which can work underground, night vision devices that work in complete darkness and remote and wire-controlled robots that can see and map tunnels without risking the lives of the soldiers. The IDF has training simulators to train soldiers in near realistic situations. Israel has also developed variety of explosives and ground penetrating munitions, like the GBU-28 which can penetrate 20 feet of concrete or 100 feet of earth.35 Israel, over the years, has used satellite imageries, aerostat cameras and radars to map the tunnel system. These assets cannot reveal the layout of the tunnels but have been used to monitor location where cement-mixture trucks have halted over the years. The general area around these locations are possible entrances of the tunnels and may be probed using low-frequency, earth-penetrating radars, or basic probes.36 US and Israel have also been collaborating to develop newer technologies. Since 2016, Congress has appropriated US$ 320 million towards the project.37 IDF’s Special UnitsFighting enemy inside subterranean system requires specialised units. The Gazan tunnels were first discovered during the first Intifada and the IDF recognised the need to raise specialised units. It raised ‘Yahalom’, specialist commandos from Israel's Combat Engineering Corps. Yahalom specialises in discovering, clearing, and destroying tunnels and has the “Yael” Company to undertake engineering reconnaissance, “Sayfan” to neutralise the threat of non-conventional weapons (weapons of mass destruction). In addition, there are two explosive ordinance disposal units, and “Samur”, which specialises in tunnel warfare.38 The IDF has a specialised canine unit, “Oketz”, whose dogs are trained in special tasks such as attack, search and rescue, explosive detection, and weapon location.39 In addition, police and intelligence services too have specialist units—“like Sayeret Matkal, the Yamam, and others—who share best practices for dealing with terrorists and combatants underground.”40 IDF’s Subterranean OperationsThe IDF’s doctrine of subterranean warfare has evolved with the development of newer technologies to counter Hamas’s underground infrastructure, which too has become increasingly sophisticated and more potent with the passage of time. Hamas fighters have advantage in narrow, dark, collapsible tunnels with which they are familiar. The IDF protocol demands that soldiers do not enter the underground structures unless it has been cleared of Hamas presence.41 It uses many of the newly developed technologies including tracker robots and explosives to map and clear the tunnels. Namer Establishes CordonIsrael has one of the world’s best protected armoured vehicles, 70-ton Namer, to assist in tunnel demolition. It is armed with active defence system to intercept incoming rockets and missiles and machine guns to fight enemy on ground. The vehicle is equipped with cameras which allows the crew to operate in the safe environment from within the vehicle. The IDF employs Namer to provide protection by establishing a security cordon around the combat engineers who undertake the task of demolishing underground infrastructure.43 Having secured the area of operation, the IDF maps the structure either by using ‘exploding gel’ or other technologies. Thereafter, it has an option of either demolish the underground infrastructure using explosives or flood it with sea water. IDF uses ‘Exploding Gel’ to Map Underground InfrastructureThe ‘exploding gel’ is used to map the underground structure. Having located the entrance to the tunnels, the army engineers fill the passage with ‘exploding gel’ and fire it using detonators. The smoke travels the passage way and is used to map the underground infrastructure and also cause casualties to anyone inside the tunnels. The composition of the gel is classified and is brought in trucks because the scale in which it is used is huge. Several tons of gel are required every few hundred metres.44 IDF Deploys Pumps to Flood the TunnelsThe IDF maintains a tunnel flooding plan. In the middle of November 2023, it deployed five very large capacity pumps, approximately three kilometres north of Al-Shati refugee camp. Each of these pumps is reported to have capacity to draw thousands of cubic meters of water per hour from the Mediterranean Sea and flood the tunnels within weeks.45 On 12 December, The Wall Street Journal reported “Israel’s military has begun pumping seawater into Hamas’s vast complex of tunnels in Gaza.”46 It is still unclear how effective this tactic will be to achieve its intended objective of demolishing the underground infrastructure. The plan, however, has a downside since it is likely to contaminate Gaza’s fresh water supply.47 ConclusionHamas has expended a large percentage of its resources—money, material, and man-hours —to develop the subterranean infrastructure as a counter to technological and resource superiority of the IDF. It is the pivot around which Hamas’s defensive and offensive operations are planned and executed. The IDF, on the other hand, has been working to develop newer and more effective counters, however, there are yet to achieve the desired result. The ongoing Israel–Hamas war will bring out several new lessons of interest to Indian Army. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Defence Economics & Industry | Israel, Hamas, Warfare, Strategy | system/files/thumb_image/2015/gaza-metro-t.jpg | |

| The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Implications for Regional Security | December 22, 2023 | Jason Wahlang |

SummaryThe Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, dating back to the Soviet times, continues to impact regional geo-political, geo-economic and strategic trends. The interests of major regional and extra-regional powers remain crucial in shaping the conflict. Azerbaijan denied Armenia’s Prime Minister Nicol Pashinyan’s accusations about planning a military provocation in Nagorno-Karabakh on 7 September 2023. The Armenian leader’s statements came after reports of Azeri troop movement across the disputed borders. These verbal confrontations have further fuelled tensions between the warring neighbours, who have been embroiled in constant ceasefire violations. The events have derailed the ongoing efforts to find sustainable peace in the South Caucasus region. The conflict, dating back to the Soviet times, continues to shape regional geo-political, geo-economic and strategic trends. Historical BackgroundThe root cause of the conflict lies in the formation of the Transcaucasia Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) in 1921 under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin. This was followed by the Soviet People’s Commissar of Nationalities, Joseph Stalin, shifting control of Nagorno-Karabakh to the Azeri side of the Republic.1 This decision sowed the seeds for Armenia’s festering resentment, demonstrated in their continuous attempts to reverse the status quo. Unlike Azerbaijan’s Turkic population, a majority of ethnic Armenians continue to primarily reside in the Nagorno-Karabakh region. Notably, the dispute persisted even after the dissolution of the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and formation of the three separate Caucasus Republics in 1936. In 1988, when the Soviet Union was nearing dissolution, the Armenian population, backed by Armenia’s SSR in Nagorno-Karabakh, protested against the Azeri government and demanded independence.2 This resulted in all-out clashes between the two ethnic communities in the Nagorno-Karabakh region. The conflict escalated following the Soviet Union’s collapse amidst the two nations gaining independence. Nagorno-Karabakh emerged victorious in 1994, and the territory remained independent from Azeri control.3 Despite being victorious, the region was primarily dependent on Armenia until 2020. Map 1: Nagorno-Karabakh Territory Post the 1994 War

The Second Armenia–Azerbaijan WarThe frozen conflict over the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh reignited in 2020 marked by the second Armenia–Azerbaijan war. It ended up altering the status quo. The war led to Azeris establishing control over large swathes of Nagorno-Karabakh following the massive military support, mainly drones, from Türkiye, which, in fact, proved to the proverbial game changer.4 It was also during this time that Russia deployed its peacekeepers in the Lachin corridor to prevent re-escalation of the conflict as per the agreement on the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh ceasefire agreement. The significance of the Lachin corridor can be gained from the fact that it is not only a humanitarian corridor but also a lifeline connecting Armenia with the people of Nagorno-Karabakh for movement of resources. The ongoing blockade of the corridor by Azeri ‘eco-activists’ has reportedly created new humanitarian challenges for Nagorno-Karabakh amidst dwindling supplies and surging demand for essential commodities. Map 2: Nagorno-Karabakh Territory after Second Karabakh War

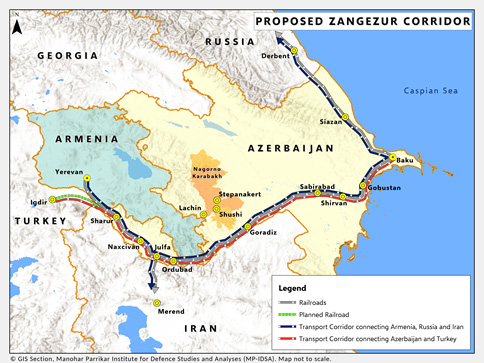

Yerevan’s PerspectiveRepublic of Artsakh (Armenian term for Nagorno-Karabakh) has been viewed as an extension of the Greater Armenian-Artsakh Connect5 , given its sizeable Armenian majority population (95 per cent population). Notably, Armenia has been viewed as Nagorno-Karabakh’s leading security provider by the territory6 and has a strong identity-based and historical connection with locals. The Ottomans, who ruled the Armenians until the First World War, have been accused by the latter of committing the Armenian genocide between 1915 and 1917.7 The Armenians believe that the Azeris, who are ethnic Turks, aim to emulate the Ottomans, perceiving the recent events as an extension of the genocide.8 Moreover, Armenians have accused the Azeris of reviving their inter-generational trauma of the Armenians by torturing Nagorno-Karabakh’s ethnic Armenians. 9 Another major factor that has fuelled Armenia’s current reaction to the conflict is its Prime Minister Nicol Pashinyan. Despite being re-elected in a snap election, his decisions have spurred protests by both locals and diaspora, who have called for his resignation. Recently, the Armenian Prime Minister recognised Azeri sovereignty over 86,000 kilometres of territory, including Nagorno-Karabakh.10 This worsened his approval rating, down to 14 per cent, among the population.11 Notably, his statements and perceived disregard for Nagorno-Karabakh’s significance for the larger Armenian society stems from a lack of connection to the conflict zone, unlike his predecessors. The first President, Levon Ter Petrosyan, was involved in the protests in the Soviet era and led Armenia against Azerbaijan during the First War. The other two leaders of Armenia, Robert Kocharyan and Sergh Sargasyan, were born in Stepanakert, Nagorno-Karabakh’s capital. Baku’s PerspectiveFor the Azeris, international recognition has been one of its trump cards when discussing the conflict. For example, the UNSC Resolution 884 on 12 November 1993 affirms Nagorno Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan.12 Azerbaijan has also frequently invoked the Soviet Union’s decision to transfer Nagorno-Karabakh to the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic. For the Azeris, the re-establishment of control over Nagorno-Karabakh was a promise waiting to be fulfilled by their incumbent leader, Ilhan Aliyev, since 2008.13 Meanwhile, efforts are underway to facilitate the return of the ‘displaced Azeri’ population, i.e., those forced out from Nagorno-Karabakh during the First War. Another corridor of significant importance to the leadership in Baku is the Zangezur (Syunik) Corridor. The idea of the corridor came into discussion only after the conflict in 2020. This proposed corridor would connect Azerbaijan with its exclave, Nakhichevan, through Syunik, a territory within Armenia. Additionally, it would ensure Türkiye’s direct land connection to Azerbaijan from Armenian territory. The corridor, if implemented, would provide a transportation route from Baku to Kars in Turkiye. Until now, Türkiye had only one border connected with the Azeri exclave Nakhichevan, which would be connected with Baku if the corridor was established. Map 3: Proposed Zangezur Corridor

Simultaneously, Azerbaijan has established a checkpoint near the Lachin Corridor. This has resulted in some Azeri eco-protestors14 blocking the corridor, affecting the local population of Nagorno-Karabakh. The corridor is critical for transporting goods and services for the local population, and therefore, any obstruction can deprive people of essential supplies. The Nagorno-Karabakh PerspectiveWith a predominantly ethnic Armenian leadership and social structure, locals see the conflict as integral to independence from Azerbaijan.15 The small Azeri presence, which existed before the collapse of the Soviet Union, has aspired to live under Azerbaijan’s control, now a possibility after the 2020 war.16 While the majority community has appreciated Armenia’s involvement in Nagorno-Karabakh, they have expressed disappointment with Nicol Pashinyan’s administration.17 The public has demanded a more proactive stance from Armenia, reminiscent of its past efforts.18 Since 2020, amidst the territorial changes, the locals’ main concern has been their future treatment by Azeri leadership, considering the ongoing hostility between the ethnic groups as well as between Armenia and Azerbaijan. These suspicions have heightened due to the Azeri blockade in the Lachin Corridor. The embargo has invited sharp criticism from Armenia as well as regional and major extra-regional powers. Notably, the United States, European Union, United Nations and France have been critical of the Azeri ‘eco-protestors’ actions.19 Genocide Watch, a prominent genocide-related organisation, has referred to the blockade as creating a genocide-like situation. It has placed the territory on Stage 9 (Extermination) and Stage 10 (Denial) of genocide.20 At the same time, Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh have frequently referred to Azeris committing cultural genocide through churches and Khatchkars’ (Armenian Crosses) destruction.21 These debates on genocide coincide with the Armenian understanding of the conflict’s current phase as an extension of the genocide carried out by the Ottomans. On the other hand, the Azeris have denied such claims and have rather blamed Armenia for provocation.22 Role of Major and Regional PowersRussia and Iran are considered Armenian allies whereas Türkiye and Israel back Azerbaijan. At the same time, the United States and the European Union (EU) appear to be seeking to expand their regional footprint. Russia remains one of the region’s key stakeholders concerning the conflict. Moscow has historically been connected to the conflict given their shared Soviet legacy. Russians have also been credited, mainly by Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, for trying to find a peaceful solution with their constant involvement in the various peace process. Russians brokered the 2020 peace deal, which involved placing Russian peacekeepers in the controversial Lachin corridor. Map 4: Lachin Corridor with Russian Peacekeepers

However, Russia has drawn criticism from the Armenian leadership for its perceived lacklustre efforts to find peace through the Collective Security Treaty Organisation.23 The Armenians expected a more proactive involvement similar to the one in Kazakhstan during the January 2022 protests. This is by virtue of Yerevan being a member of the CSTO with Russia having a military base in Gyumri. Armenia and Azerbaijan have been part of the European Union’s Eastern Partnership since 2009. However, Azerbaijan is considered closer to the EU than Armenia given the latter’s membership in Russia dominated Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) and CSTO. Notably, Europeans have traditionally supported Azeris due to Armenia’s robust partnership with Russia. Nevertheless, the somewhat strained relationship between Russia and Armenia amidst European efforts for peace is being increasingly viewed positively by Armenian leaders including inviting the peace missions.24 This indicates a potential Armenian shift towards Brussels in the long term. The EU has led peace missions and organised several meetings between government officials to establish regional peace. For example, the EU established two EU Missions; the first lasted for two months (October 2022–December 2022), and the second would be present in the Armenian territory till 2025, the same year the Russian peacekeepers would leave Lachin.25 However, the EU mission’s mandate is limited to Armenia due to Azerbaijan’s refusal to allow them into Azeri territory.26 This has, however, not affected the relationship between the EU and Azerbaijan. The United States’ involvement in this region could be linked to exploiting any vacuum created by Russia due to its involvement in Ukraine. The regional geopolitical turmoil could see the US attempt a more hands-on approach. The US has sought to play the role of a peace negotiator and moderator between the two governments while also being a member of the OSCE Minsk peacekeeping initiative. The latest involvement of the United States in the region is the 10-day routine military exercises it conducts with Armenia in Yerevan.27 Türkiye has a strong relationship with its Turkic brethren in Azerbaijan and sees it as a gateway to the region.28 Its ties with Armenia are almost non-existent, mainly due to the historical animosity that exists due to Türkiye’s predecessor—the Ottoman Empire. Since Türkiye sees Azerbaijan as its primary contact point, it has developed a strong relationship with it. Türkiye’s diplomatic and military support, particularly its famed Bakhtiyar drones, proved decisive for Azerbaijan in the second war.29 Iran remains a close partner of Armenia despite recognising Nagorno-Karabakh as Azeri territory as per international norms. Iran’s closeness to Armenia is also co-related to its regional hostility with Israel, which provides Azerbaijan with 70 per cent of its total military supplies.30 This threat has existed since the 1990s with the first post-soviet Azerbaijan President, Abulfaz Elchibey, threatening to march to Tabriz (Azeri-populated Iranian territory),32 to the current establishment of Ilhan Aliyev declaring the need to secure minority Azeris in Iran. He referred to them as his ethnic kin.33 Mahmudali Chehreganli, the self-proclaimed and exiled leader of South Azerbaijan (North West Iranian territory) National Awakening Movement, in an interview with state-run AZ TV, called for the overthrow of the Iranian leadership, terming it as hateful.34 Such threats have risen after the 2020 conflict, particularly after Azeri successes on the battlefield.35 Meanwhile, Iran’s dispute with Azerbaijan is also regarding the establishment of Zangezur corridor, which would connect Baku with its enclave Nakhichevan, the closest border that Iran shares with Azerbaijan.36 Türkiye supports the corridor’s idea, whereas Iran and Armenia have been opposed to it.37 Iran fears that the corridor could block Iranian land connection to Armenia if it exists.38 This would also obstruct its connection with Georgia which bypasses Azerbaijan and Türkiye. It has led Iran to be vocal against any territorial changes within Armenia which could happen due to the corridor. ConclusionThe frozen conflict, reignited in 2020, remains the key hurdle to sustainable peace in the Caucasus. It continues to undermine regional security. Amidst continued ceasefire violations and lack of peace treaty, the solution to the conflict appears to be a distant dream. Meanwhile, the interests of regional and extra-regional powers remain crucial in shaping the conflict. Russia’s war in Ukraine may see Moscow cede ground to others in what has been Russia’s traditional sphere of influence. Recently, Armenia recalled its envoy to CSTO amidst murmurs of discontent with the military organisation remaining neutral in Armenia’s moment of national crisis. As such, the US and the EU in particular could seek to expand their footprints in the region amidst the overhang of Russia–West confrontation. Notably, older peace formats, including the OSCE format for peace, which was instrumental in negotiating a peace deal during the 1990s, appear to have lost relevance. Instead, peace deals proposed by Iran and Türkiye have gained traction, thereby highlighting their growing regional influence in the Caucasus. However, given the strained relations of these countries with the warring nations, i.e., Iran with Azerbaijan and Armenia with Türkiye, the chances of concluding a credible peace treaty appear slim. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Europe and Eurasia | Azerbaijan, Armenia | system/files/thumb_image/2015/armenia-azerbaijan-t_0.jpg | |

| Assessing Japan’s Diplomacy in 2023 | December 21, 2023 | Arnab Dasgupta |

Japan has had a busy diplomatic year. It had to adapt its foreign policy on account of the structural challenge posed by China and was also called upon to display dexterity as a gamut of old and new territorial and ideological conflicts reignited in West Asia and Eastern Europe. Japan’s neighbourhood underwent milestone shifts that required deft tending by Tokyo. The infusion of defence-oriented language into its rhetoric had to take into account reactions across all of Asia and the world. Further, due to an internal political reshuffle, Japan has had two foreign ministers, giving rise to the unusual phenomenon (in Japan) of a prime minister explicitly staking a claim to make a personal impact on foreign policy. Given these trends, Japan’s diplomacy in 2023 marks a significant inflection point. Rapprochement with the Global SouthThe first key trend noticeable in Japan’s foreign policy in 2023 has been its ardent embrace of the Global South concept. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida chose the occasion of his visit to New Delhi in March to announce his new plan for a Free and Open Indo-Pacific.1 This plan gave importance to South and South-East Asia as well as Africa as key regions for Japan’s strategic engagement. Kishida’s invitation to India and Indonesia, two leading Global South nations, to the G-7 summit in Hiroshima, as well as his interactions with Global South leaders during the G-20 summit in New Delhi,2 spoke about Japan’s sincerity in putting its rhetoric into practice. Kishida was ably assisted in this enterprise by Foreign Ministers Yoshimasa Hayashi and (post-September) Yoko Kamikawa. Both Hayashi and Kamikawa used their visits to Global South countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America to reinforce Japan’s commitment to convey their concerns to the industrialised Global North. Even the Imperial family was roped into the role of de facto ambassadors of Japan’s message. Emperor Naruhito and Empress Masako visited Indonesia in June, Crown Prince Fumihito (the Emperor’s brother) and Crown Princess Kiko visited Vietnam in September, while Princess Kako’s (daughter of the Crown Prince) successful visit to Peru in November compensated for the lack of visits by Kishida to the region. Neighbourhood DiplomacyDevelopments in the neighbourhood added new dimensions to Japan’s diplomatic calendar. The inauguration of a new President of the Republic of Korea, Yoon Suk-Yeol, in December 2022 augured a sea-change in that country’s blind-spot towards Japan. Yoon surprised many among his own countrymen by seeking out an engagement with Kishida in March. The engagement followed a long freeze in bilateral ties after the previous South Korean administration of Moon Jae-in allowed a Supreme Court judgement on Japan’s historical atrocities in the peninsula to affect bilateral security and political cooperation in 2018. Since that first meeting in March, Yoon and Kishida met each other seven times over the next nine months,3 a frequency rare in the annals of diplomacy. During Kishida’s visit to Seoul in May, Yoon went further than any other South Korean leader in de-emphasising issues of history, wholeheartedly echoed by Kishida. The rapid improvement in ties resulted in some tangible benefits. The ROK did not oppose Japan’s release of seawater used in the clean-up of the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor in August. Yoon and Kishida, in association with President Joseph Biden, agreed to resume joint military and security cooperation against the actions of North Korea and China.4 China itself proved to be the elephant in the room in 2023, particularly in the latter half of the year as Japan embarked on the wastewater discharge from the Fukushima Daiichi plant. It not only insisted on opposing the United Nations specialised agencies’ stance on the safety of the discharged water, but also embarked on an unprecedented campaign against Japanese citizens, mobilising crowds to vandalise the Japanese Embassy and a Japanese school, pre-emptively banning seafood and other exports from Japan, and encouraging a unique prank-call campaign against Japanese domestic entities.5 Japan also showed willingness to escalate matters by joining with the US and the Netherlands to restrict Chinese access to advanced semiconductor manufacturing technology in October.6 Japan widened its sanctions list in December to include Chinese government labs engaged in nuclear research as a protest against the latter’s expansion of its nuclear arsenal.7 Nevertheless, the two sides did resume informal military talks,8 and Kishida met President Xi Jinping on the side lines of the APEC Summit in November to discuss bilateral issues.9 Emphasising Defence TiesAnother discernible trend in Japan’s diplomacy in 2023 was the uptick in mentions of defence and security issues in its engagements with relevant countries. Kishida’s visit to New Delhi in March saw him engaging Prime Minister Narendra Modi on issues of defence technology cooperation. Kishida’s public commitment later in the summer to reconsider Japan’s strict curbs on export of lethal defence technology in the teeth of opposition from pacifist quarters of the Japanese political sphere saw him using his visit to Ukraine as an opportunity to shake up established norms. His subsequent visits to North Africa and South-East Asia, as well as those of his deputies to Europe, the US and West Asia have shown a consistent throughline under which Japan has committed to work cooperatively with partners and like-minded countries to ensure not only maritime security, but, as part of its comprehensive national power, economic, energy and technology security as well. One of the most distinctive advances under this overarching theme has been the introduction of the Official Security Assistance (OSA) program10 as a complement to its Official Development Assistance. With an initial budget of 450 million Japanese yen, the OSA is intended to provide non-lethal security assistance to key countries. The first recipients, Fiji, Malaysia, the Philippines and Bangladesh, are indicative of Japan’s areas of interest, and Tokyo has shown its openness to considering an expansion of the program to a global scale in partnership with other net security providers in their respective regions. The fact that the Philippines is presently embroiled in a stand-off against China in the Second Thomas Shoal indicates Japan’s strategic choice in ensuring smaller countries are capable of pushing back against Chinese maritime aggression. Enhancement of the Prime Minister’s RoleThe year 2023 also marked the year when Japan’s diplomacy underwent an institutional reworking in terms of who ‘does’ foreign policy. In essence, this change turned the Japanese prime minister into the key effector of policies, with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs being placed in a secretarial role. Evidence of this could best be found in the announcement of the replacement of Yoshimasa Hayashi as the nation’s chief diplomat while Hayashi was on a trip to Ukraine, and the rapid substitution of Yoko Kamikawa—with no significant prior experience of foreign affairs, to the position. Kishida’s desire to take a greater role in foreign affairs came from a press conference he delivered in the wake of the reshuffle of his cabinet in September. He noted that while “[m]inisters have an important role to play…summit diplomacy is a big component as well. I myself intend to play a major role in such summit diplomacy.”11 As observers of Japan’s political arena know well, Japanese prime ministers tend not to be primarily aggressive salesmen of their country abroad, choosing to focus instead on leaving behind domestic legacies. Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda is the epitomical example. A former bureaucrat, he was central to the engineering of the ambitious industrial policies that caused what we now know as Japan’s high-speed economic growth era, from 1960 to 1973. Some prime ministers, to be sure, have been outward-looking in terms of their legacy-building: Shigeru Yoshida, father of the Yoshida Doctrine espousing close security ties with US in lieu of a focus on economic growth at home, and Shinzo Abe, come to mind. However, none so far have staked quite such an overt claim to diplomatic primacy as Kishida. It is widely speculated, to some extent justly, that Kishida’s low domestic support ratings, due largely to internal policy failures such as the talk of new taxes to increase defence spending and the failure to completely repudiate the Liberal Democratic Party’s cosy ties with the controversial Unification Church, may have led him to seek diplomatic successes. However, this remains a double-edged sword. Should his key initiatives, such as the OSA or outreach to the Global South, sour, he will be doubly blamed for frittering away valuable policy space to pursue arcane objectives abroad. As such, Kishida’s ensuing moves in this sphere bear observation. ConclusionIt is interesting to note that Japan, despite its long-standing image as a staid, reactive power, stands at a diplomatic crossroads of increasing significance at the end of 2023. Which road it takes in 2024 is not easy to predict, but there are certain significant mileposts which could signal the direction. One crucial milepost will be how Japan manages its ties with the Global South, especially with India. Another crucial marker will be the success (or failure) of its new policy of studied neutrality in West Asia, which will indicate whether it is prepared to deviate from the Western world’s script should its interests be seriously affected. Third, and finally, it would be interesting to see whether Prime Minister Kishida continues to expand his role in diplomacy, and to what extent he can claim the space to do so before encountering significant bureaucratic pushback. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

East Asia | Japan | system/files/thumb_image/2015/japan-t_0.jpg | |

| India–Nigeria Defence Cooperation: Contexts, Drivers and Prospects | July-September 2023 | Eghosa E. Osaghae |

Nigeria and India have a long history of cordial and robust bilateral relations and defence cooperation. This article examines the nature, contexts, drivers, content and future of defence cooperation between the two countries in terms of continuity and change. It analyses how global and African currents including rivalry amongst world powers and the new scramble for Africa, as well as transformations and changes in the conceptions and challenges of security, have shaped defence relations between them. From the ‘traditional’ and more historically continuous domains of peacekeeping, military training and capacity-building, the scope of cooperation has expanded to include non-kinetic approaches to defence, counterterrorism, counterinsurgency, cybersecurity, research and development, medical security, and maritime security in the oceans and blue economy. The article shows that defence cooperation has been revitalised and enlarged since Nigeria’s return to civil democracy in 1999, and concludes that although Nigeria and India are unequal partners and Nigeria is more dependent on India’s benevolent power, military goods and services, defence cooperation has been mutually beneficial to both countries. |

||||

| India–Africa Military-cum-Defence Diplomacy: A Viable Option | July-September 2023 | Swaim Prakash Singh |

The relationship between India and Africa is based on historical ties forged during colonialism and apartheid. However, due to a wave of liberalisation and privatisation in the 1990s, India’s involvement in Africa shifted significantly. Despite active engagement for more than 70 years, India’s long-term strategy for expanding its relations with Africa lacked clarity and wherewithal. As a result, India has also been unable to capitalise on its enormous historical goodwill in the region. However, it may change as ideological and political issues are taking a backseat. Also, rising economic and security ties have recently given the partnership a fresh start. However, given the unprecedented opportunity to engage with African countries to address their security concerns and thus strengthen relations, it is observed that initiatives to this end are insufficient. What else can be done to make the engagements more meaningful and worthwhile? Can the defence diplomacy factor be one of the strategies for strengthening bilateral security cooperation? Can the bilateral engagement move to other military arenas beyond UN Peacekeeping Operations? Can the Indian military contribute more to the African countries’ capacity-building? Can India think of establishing a military base beyond the maritime domain? Can India capitalise on Africa in its effort of ‘Atmanirbharta’ to ‘Bharatnirbharta’? This article attempts to answer these questions by focusing on the need for India and Africa to strengthen their relationships at all levels, particularly in defence and military diplomacy. |

||||

| India–Africa Defence Cooperation | July-September 2023 | G.G. Dwivedi |

India and Africa are bonded by centuries old historic ties, which are deeprooted, diverse and harmonious. As geographic neighbours, the two are linked by the Indian Ocean. Given the shared past, diaspora connection and future aspirations, India and Africa are natural partners. With the formation of India–Africa Forum Summit (IAFS) in 2008, bilateral cooperation gained huge traction and mechanism became more structured. India has accorded top priority to Africa in its foreign policy and strategic calculus. Consequently, 18 new embassies/ high commissions have been added over the last five years, taking the numbers to 47. Even bilateral trade has shown a sharp increase, of US$ 98 billion in 2022–23. During the COVID-19 pandemic, India took a number of steps to help Africa by expediting the delivery of essential medicines and vaccines. |

||||

| UN Peacekeeping Operations: Challenges and Prospects in South Sudan | July-September 2023 | G. Praveen |

A country which has one birth every 1.63 minute and one death every 4.62 minute, with an approximate population of 11 million plus (estimated, as last official census was by Sudan in 2008), of which 8.3 million (including 4.4 million children) need humanitarian assistance, needs more than good governance to prevent utter collapse. This article explores the drivers of conflict in South Sudan and the peacekeeping challenges that the UN Mission in South Sudan faces, especially at a time when the country is preparing for long-pending elections, post formation of a revitalized government, which is by itself a proportional mix of various warring factions. The article posits that an integrated effort from traditional friends of South Sudan like the Troika (Norway, UK, Ireland), AU, EU, and other agencies, in the domains of SSR and DDR, legal structures, funding for capacity-building, election process, etc., combined with effective peacekeeping by UNMISS and implementation of the four key pillars of the mandate is necessary for a stable future. |

||||

| Maldives and the #IndiaOut Campaign | December 13, 2023 | Tejusvi Shukla |

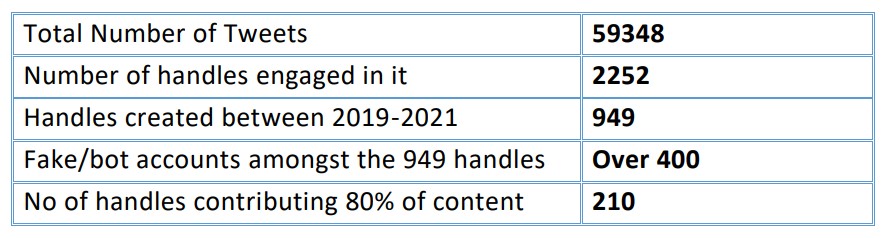

President Mohammed Muizzu of Maldives confirmed on 4 December 2023 that an agreement was reached with India for the withdrawal of over 70 troops deployed in the archipelago nation for Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) and training purposes. This statement was made after his return from the UAE and Turkey. Two Dhruv Advanced Light Helicopters and a Dornier aircraft are expected to continue to be deployed in the Maldives.1 Muizzu had requested India to withdraw its military personnel formally when he met the Minister of Earth Sciences Kiren Rijiju in Male on 18 November 2023. This was also a key election campaign promise of the incumbent, who took over power in September 2023. The shift in Maldives foreign policy is not sudden. It is a result of a simmering anti-India sentiment dating back to at least a decade, which played up fears of India gradually attempting to impinge on Male’s sovereignty. These sentiments got briefly stabilised under the Solih government since 2018, but peaked during the 2023 presidential campaign. Moreover, this is not an organically generated sentiment. It has been actively fanned, and is reflective of undertones of a well-crafted war of narratives that facilitated the changing domestic realities in the country. The foreign policy shift has witnessed a leap from a call for ‘India First’ under former President Ibrahim Solih to ‘India Out’ that was central to Muizzu’s presidential campaign. Tracing the TrajectoryThe genesis of the India Out campaign in the Maldives can be traced back to the political landscape of 2013, when the government of Abdulla Yameen assumed power. Yameen's administration, marked by an unequivocal pro-China stance, entered into a series of opaque infrastructure agreements with Chinese state-owned enterprises. During the five years of his rule, as the country slid into various Chinese ‘debt trap’ investments, his governments’ conscious efforts at framing the cognitive environment by raising an India-phobic campaign began. A popular discourse emerged surrounding the agreement for receiving two Indian Dhruv Advanced Light Helicopters and an accompanying contingent of Indian armed personnel, integral to the training of the Maldives National Defense Forces for helicopter operations. Raging disinformation campaigns generated social panic suggesting Indian designs to impinge on the nation’s sovereignty. By 2015, Yameen terminated the agreement with India. Yameen’s tenure was marred with dubious infrastructure project deals with Chinese-owned companies and human rights abuses. He lost in 2018 elections, and Ibrahim Solih became the president.2 Solih reaffirmed the traditional ‘India First’ policy and his tenure was marked by the re-signing of the agreement relating to the Dhruv helicopters. Furthermore, in 2021, India and the Maldives entered into the Uthura Thila Falu (UTF) development deal concerning port construction.3 While Solih's ascendancy provided some respite for New Delhi, the anti-India sentiment among the population kept simmering. The controversial discourse surrounding Indian military presence re-emerged in the form of the ‘India Out’ campaign in print as well as social media and on the Maldivian streets. Notably, the Indian High Commission became a focal point for expressions of this anti-India sentiment, with Indian diplomats being targeted on various social media platforms.4 The Case of Dhiyares NewsThe role of a local news outlet called Dhiyares News assumed significance, with even the ruling Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) charging that the “continuous barrage of anti-India vitriol” by the outfit appeared to be a “well-funded, well-orchestrated and pre-meditated political campaign with the express purpose of whipping up hatred against the Maldives’ closest ally, India.”5 Former President Yameen, who was released from jail by then, assumed a leadership role in the ‘India Out’ campaign. His involvement added a layer of complexity, considering his previous alignment with pro-China policies. The presidential campaign of Muizzu, a PNC candidate who was a coalition partner of Yameen’s former party PPM, was centered on fanning the social panic generated through the campaign, which eventually ended up in the fall of the Solih government. It is pertinent to highlight the orchestrated war of narratives over the issue. A report by the Colombo Information Agency serves as an eye-opener in this context. As the activity on Twitter (where the ‘India Out’ campaign spread most as the hashtag #IndiaOut) was tracked, it was notable that the 59.3k tweets using the hashtag were tweeted by a mere 2,252 handles—almost half of which were created between 2019 and 2021. Moreover, approximately half of these newly created handles in turn were identified as fake. According to the report, around 210 handles were responsible for 80 per cent of the content engagement where a mere eight handles contributed to over 12,171 tweets.6 The report further examined the role of Dhiyares News and its sister journal The Maldives Journal in driving this campaign. The journal, professing an anti-India sentiment, was sympathetic to former President Yameen’s cause, and had an openly pro-China stance. The journal published articles titled “Yameen tortured on Modi’s Orders: Opposition”8 and targeted Indian presence and alleged “interference” in Male’s internal affairs. The role of the co-founder Azad Azaan was highlighted in the report. Of the 2,252 handles which engaged in the sharing of the hashtag, the report noted that half of them were followers of Azaan, where his account managed to single-handedly attract 12 per cent of the total traction.9 Azaan’s pro-China alignment is also well known. Regardless, the fact that this orchestrated disinformation campaign could be transformed into an organic public discourse that defined the presidential elections of a country speaks volumes of the cognitive vulnerabilities existing in contemporary times. Going ForwardIndia has been the first responder to each of Maldives’ political, economic, and natural disasters. Despite this, the generation and seeming acceptance of an anti-India sentiment due to dis-information campaigns is significant. Popular perceptions got manipulated which in turn changed the domestic political mood and political dynamics, and subsequently the fate and direction of the country’s diplomatic engagements. While discussing ways to defeat an adversary through covert means, Kautilya’s sutra in the second chapter of his twelfth book of Arthashastra states “एवं जानपदान्समाहर्तुर्भेदयेयुः”. This roughly translates as “...in the same manner, they should divide the country people from the Administrator” (12.2.29). As democracies function in the contemporary scenario, any state’s sovereignty lies in its population, making favourable popular perceptions central to any diplomatic pursuits. Bilateral ties are only as strong as the support that a partner government can generate in favour of a policy. Regardless of the changing domestic realities in Male, India’s regional and geopolitical relevance will continue to keep relations with New Delhi among Male’s high-priority affairs. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

South Asia | India-Maldives Relations | system/files/thumb_image/2015/ind-maldives-t_0_0.jpg | |

| Getting China Wrong | November-December 2023 | Anshu Kumar |

The history of international relations has rarely witnessed a faster-growing State than China on the world platform. One of the major reasons attributed for China’s rise is the US’ engagement policies. For decades, debates surrounding engagement policies have captured the attention of academicians, policymakers, and politicians. Some scholars had believed that China’s inclusion in the liberal international fold would transform its political and economic system in line with democratic and free-market principles, respectively. Others were sceptical about any such miracle. |

||||

| Contemporary Issues on Governance and Security in Africa | November-December 2023 | J.M. Moosa |

The volume under review is an outcome of an effort to understand the convergence of governance, conflict, and security in Africa. It contends that while there is a large body of work on conventional security threats, only some exist on other emerging threats to human security. While cases of armed insurgency have declined, other forms of violent conflict that endangered lives and property have increased. The book considers the shrinking of many African States as one of the main causes of this increase in violent conflicts. Many of these States exhibit incapacity to ensure peace and security within their confines. In addition, many States are experiencing a resurgence of conflict over water and land. Authors contend that a strong correlation exists between conflict, security and development, and the shifting nature of conflicts in Africa needs a fresh approach and perspective. |