You are here

Putin’s Visit to North Korea: An Assessment

Summary

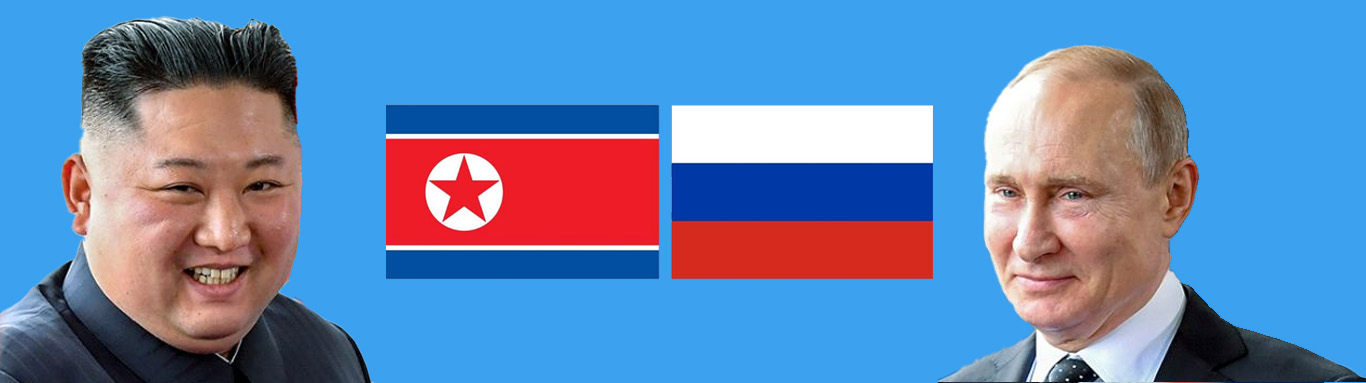

President Vladimir Putin’s first visit to North Korea in almost quarter of a century came on the heels of his counterpart Kim Jong-Un’s visit to Russia last year, thereby highlighting the growing warmth in bilateral ties. New equations appear to be developing anchored to a strong personal rapport between the two heads of states. Overlapping interests and some caution are likely to be the North Star of bilateral ties.

Introduction

Russian President Vladimir Putin paid an epochal visit to North Korea on 18–19 June 2024.1 This trip to Pyongyang, Putin’s first in almost quarter of a century, came on the heels of his counterpart Kim Jong-Un’s visit to Russia last year,2 thereby highlighting the growing warmth in bilateral ties. Amidst the apparent bonhomie between the two heads of states, Putin, unsurprisingly, received a red carpet welcome marked by attendant pomp and publicity. Both sides also celebrated the 75th anniversary of establishment of diplomatic ties.

The highlight of the visit was the signing of ‘Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the Russian Federation’. Reminiscent of the 1961 Treaty signed between Nikita Khrushchev and Kim II-Sung, the new agreement appears extraordinary in its scope and depth. This is particularly relevant given the fact that Russia had earlier supported United Nations Security Council (UNSC) sanctions on the North Korean regime.3 These sanctions culminated in Pyongyang’s international isolation.

In a major shift in Russia’s strategy, Putin spoke of the need to ‘revise’ UNSC sanctions.4 Incidentally, the new Treaty pledges to develop robust bilateral economic partnership. Its pièce de résistance, however, is on mutual defence as elaborated in Article 4:

If one of the Parties is subjected to an armed attack by any state or several states and thus finds itself in a state of war, the other Party will immediately provide military and other assistance with all means at its disposal.5

Drivers of Engagement

Russia building new equations with North Korea reflects a significant volte face from its position on the Korean peninsula in the last two decades. Driven by its Pivot to Asia in the early part of this millennium, Moscow had sought rapprochement with Japan and South Korea for their markets, investments and technologies.6 This was a key determinant in the Kremlin joining the West at the UNSC in imposing sanctions on North Korea.

Crucially, Russia’s strategy reaped rich dividends. Robust trade and investment linkages were established with Tokyo and Seoul. These two Asian economic powerhouses emerged as vital partners for Russia’s economic transformation, particularly in the development of its underdeveloped Far East and the Arctic. Notably, these resource-rich regions comprise 66 per cent of Russia’s territory and only 15 per cent of its population. And they are seen as key drivers of Russia’s future growth.

Russia’s rapprochement with the traditional Western partners in Japan and South Korea did not stop Moscow from deftly maintaining friendly but stagnating ties with the North Korean regime. This was in sharp contrast to the Cold War era. The Soviet Union was a critical partner in strengthening DPRK’s comprehensive national power.7

Incidentally, the geographical location of the Far East makes Russia a stakeholder in the geopolitics of North-East Asia. The Vladivostok port, Russia’s principal commercial port in the region and home to its Pacific Fleet, is flanked by the Korean peninsula on one side and Japan on the other. Russia shares a 17 kms long border with North Korea as well.8

Putin’s recent visit, therefore, signals Russia’s expectations of a long-term break with Japan and South Korea. These two Asian states have sided with the West in boycotting Russia for invading Ukraine. Their growing hostility with Moscow is evident in Tokyo9 and Seoul10 not only imposing sanctions on Russia but also providing Kiev with economic aid.

As such, Russia rebuilding its partnership with North Korea appears linked to Moscow’s broader strategy of strengthening ties with countries who follow an independent foreign policy and do not join Western efforts in isolating the Kremlin. From this flows Russia’s strategic necessity of seeking new avenues of investment, technology and markets especially in areas where Russia retains a competitive advantage. These include defence, hydrocarbons and raw materials. And Pyongyang could present new opportunities for collaboration.

Notably, North Korea has offered ‘unwavering support’ to Russia’s war efforts.11 In this, Moscow and Pyongyang have a shared interest in tackling what they perceive to be US unilateralism. This was aptly reflected in Putin’s statement of ‘two persecuted but resilient victims of an aggressive United States’.12 He added:

At present, we are combatting together the hegemonism and colonial practices of the United States and its satellites and are resisting attempts to impose alien development models and values on us. Russia and Korea have a similar proverb, it goes as follows: a close neighbour is better than a remote relative. I think that this folk wisdom fully reflects the nature of our countries’ relations.13

Moreover, Putin’s visit is likely intended to send a strategic message about Russia's continued relevance on the global stage. This is part of Russia’s projection of itself as a global pole. In fact, Russia’s espousal of multipolarity is anchored to preventing the rise of a G2—the Kremlin’s worst-case scenario in its global power aspirations.

Meanwhile, North Korean ammunition could boost Russia’s firepower in Ukraine. There have been widespread reports of Pyongyang supplying lethal equipment to Russia, particularly 155 mm shells.14 While the extent of this support is yet to be fully ascertained, the level of consternation in the West points to substantial transfers.

Similarly, North Korean labour could be tapped to fill Russia’s growing industrial and agricultural labour shortages.15 Conscription has accentuated the shortfall caused by the trend of a declining Russian population.16 Russia’s Central Bank head Elvira Nabiullina has pointed out that labour shortage rather than lack of finance is restraining domestic production.17 A similar view was echoed by the Minister of Economic Development Maksim Reshetnikov at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum held in June 2024.18 There are reports that Russia’s population could decline to 139 million from the current 146.1 million by 2046.19

In the same vein, the mutual defence clause could be Russia’s signal to Japan and South Korea to resist from military supplies to Kiev or face a more emboldened and stronger North Korean regime anchored to Russia’s strategic support. Putin warned Seoul of ‘actions which South Korea would hardly welcome’ if it exported lethal weapons to Ukraine.20 The timing of this statement can be linked to reports of Seoul re-evaluating its position on supplying arms to Kiev.

Incidentally, Russia upgrading its ties with North Korea also highlights Kremlin’s strategic autonomy vis-à-vis China. It is particularly relevant amidst growing perceptions of Moscow being relegated to Beijing’s subordinate partner. This sentiment is appearing to cause unease in Moscow. Putin’s embrace of Kim could strengthen North Korea’s hand vis-à-vis China—long considered Pyongyang’s principal strategic partner. Russia’s North Korean outreach could, thus, also be linked to its aspiration of being counted as an independent pole while dispelling the perception of it riding the coattails of China to stay relevant on the global stage.

For North Korea, a robust relationship with Russia—a P5 member—is likely to bring its own concomitant benefits. Kim could seek to tap Russia’s diplomatic heft to dilute Pyongyang’s isolation. He could also play the Russia card to deter the West amidst North Korea pushing the regional security envelope. Notably, Russia had earlier this year vetoed a UNSC resolution on renewing the mandate of UN Panel of Experts (PoE).21 The PoE is tasked with enforcing UNSC sanctions on North Korea for its nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles programme. Kim could even leverage the qualitative improvement in ties with Russia to seek more concessions from his core key strategic partner in China.

Meanwhile, North Korea could get access to Russia’s defence and space technologies. Reading the tea leaves from Kim’s visit22 to Vostochny cosmodrome last year, Russian assistance could fill the technical gaps confronting North Korea’s space and missile programme. Similarly, Russian energy and food supplies could alleviate North Korea’s perennial scarcity.23 Russia in any case would have surplus of these vital commodities amidst their boycott by the West—the Western market was Moscow’s biggest till the onset of the war in Ukraine.

It is, therefore, unsurprising that Kim has emerged as one of the most vocal supporters of Russia. This was reflected in his statement:

During his visit to Russia in September 2023, Kim had spoken on supporting Russia’s ‘sacred struggle’ and wishing for ‘new victory of great Russia’.25 North Korea has also recognised the independence of breakaway Ukrainian regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, now under Russian control.26

Regional Security Architecture

Putin’s visit highlights the indivisibility of security amidst growing inter-connectedness between Euro-Atlantic and North-East Asian theatres. A key feature of this is stakeholders in one theatre taking steps which could up the security ante in the other. This has seen North Korea allegedly supply ammunition to Russia in the latter’s war against Ukraine while Pyongyang’s strategic rivals in Japan and South Korea aid Kiev’s resistance against Moscow. Similarly, Russia’s support could embolden Kim to intensify his sabre-rattling in North-East Asia.

Notably, the US, Japan and South Korea have jointly expressed concern about the impact of Putin’s visit. Their joint statement stated:

The United States, ROK and Japan condemn in the strongest possible terms deepening military cooperation between the DPRK and Russia, including continued arms transfers from the DPRK to Russia that prolong the suffering of the Ukrainian people, violate multiple United Nations Security Council Resolutions, and threaten stability in both Northeast Asia and Europe… The United States, ROK, and Japan reaffirm their intention to further strengthen diplomatic and security cooperation to counter the threats the DPRK poses to regional and global security and to prevent escalation of the situation. The U.S. commitments to the defense of the ROK and Japan remain ironclad.27

Amidst a clear division of camps, new insecurities could lead to new recalibrations. This could see Japan and South Korea further strengthen their security embrace of the United States apart from beefing their own defence and deterrence capabilities. Kim recently alleged an ‘Asian version of NATO’ being formed by Washington, Tokyo and Seoul.28

However, the devil as always lies in the details. And Putin’s visit, while high on optics, did not reveal much in terms of concrete deliverables. Arguably, neither Russia nor North Korea are dependent on their mutual defence treaty to wade off existential threats. Their nuclear arsenal is their most potent insurance. Russia is also likely to be wary of sharing sophisticated defence technologies given North Korea’s famed unpredictability as well as seemingly cavalier attitude on proliferation. Russian weapons and know-how could fall into the hands of both adversaries and non-state actors, which in turn could spiral into new security threats. Similarly, the Kremlin is unlikely to take steps which would undermine China’s interests in the latter’s immediate neighbourhood.

In this, the position of China is worth deciphering. The Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson limited himself to calling Putin’s visit a ‘bilateral engagement between Russia and the DPRK’.29 Preoccupation with Russia and North Korea could lead to a diversion of the US focus away from America’s China strategy. However, Beijing could be wary of further instability on its periphery. Ongoing developments could provide a pretext for the US to expand its military presence in the region along the lines of the induction of THAAD missile defence system in South Korea. Notably, both Seoul and Tokyo are now regular participants in NATO summits.30 A new front of armed hostilities is unlikely in China’s interests.

For India, North Korea’s well-documented history of clandestine and illegal nuclear weapons collaboration with Pakistan is worrisome. So is Pyongyang’s arms transfers to non-state actors. Moreover, further instability in the Korean peninsula could put roadblocks in the goal of building robust developmental partnerships in the broader Indo-Pacific as part of Quad and Quad Plus formats. There could also be expectations from these Quad stakeholders of India’s support on their security concerns, drawing in the Russia factor in the region.

Consequently, new equations are developing in the Russia–North Korea partnership anchored to a strong personal rapport between the two heads of states. Overlapping interests and some caution are likely to be the North Star of bilateral ties. However, these emerging trends have the potential to add new fuel to existing contestations and rivalries.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “Russia-DPRK Talks”, President of Russia, 19 June 2024.

- 2. “At Vladimir Putin’s Invitation, Chairman of State Affairs of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Kim Jong-un Will Visit Russia”, President of Russia, 11 September 2023.

- 3. “Russia's Medvedev Calls for Ways to Deter N.Korea”, Reuters, 4 June 2009.

- 4. “Press Statements Following Russia-DPRK Talks”, President of Russia, 19 June 2024.

- 5. “Treaty on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and the Russian Federation”, KCNA, 19 June 2024.

- 6. Alexander Lukin, “Russia’s Pivot to Asia: Myth or Reality?”, Strategic Analysis, Vol. 40, No. 6, 2016, pp. 573–589.

- 7. “Article by Vladimir Putin in Rodong Sinmun Newspaper, Russia and the DPRK: Traditions of Friendship and Cooperation Through the Years”, President of Russia, 18 June 2024.

- 8. “In Russia's Pacific Port, Residents Await North Korea's Kim Jong Un”, Reuters, 11 September 2023.

- 9. “Japan Committed to Long-term Public-Private Aid to Ukraine”, The Japan Times, 4 April 2024.

- 10. “South Korea to Reconsider Providing Weapons to Ukraine”, Reuters, 21 June 2024.

- 11. “Beginning of Russia-DPRK Talks”, no. 1.

- 12. “Japan Committed to Long-term Public-Private Aid to Ukraine”, no. 9.

- 13. “Reception Hosted by Chairman of State Affairs of the DPRK in Honour of the President of Russia”, President of Russia, 19 June 2024.

- 14. “Pyongyang’s Pursuit of Nuclear Weapons Continues to Undermine Global Disarmament, Non-Proliferation Regime, High Representative Warns Security Council”, United Nations Meetings Coverage and Press Releases, 28 June 2024.

- 15. “Statement by Bank of Russia Governor Elvira Nabiullina in Follow-up to Board of Directors Meeting on 7 June 2024”, Bank of Russia, 7 June 2024.

- 16. “Russia's Population Could Fall to 130Mln by 2046 – Rosstat”, The Moscow Times, 10 January 2024.

- 17. “Worker Shortage is Restraining Production, Says Russia's Central Bank”, Reuters, 8 April 2024.

- 18. “The Achieved National Goals Allow Russia to Set Ambitious Tasks for the Future”, SPIEF’24.

- 19. “Russia's Population Could Fall to 130Mln by 2046 – Rosstat”, The Moscow Times, 10 January 2024.

- 20. “Press Statements Following Russia-DPRK Talks”, no. 4.

- 21. “Security Council Fails to Extend Mandate for Expert Panel Assisting Sanctions Committee on Democratic People’s Republic of Korea”, United Nations Media Coverage and Press Releases, 28 March 2024.

- 22. “Formal Dinner in Honour of Chairman of State Affairs of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea Kim Jong-un”, President of Russia, 13 September 2023.

- 23. “North Korea's Kim Warns Failure to Provide Food a Serious Political Issue”, Reuters, 25 January 2024.

- 24. “Press Statements Following Russia-DPRK Talks”, no. 4.

- 25. “Formal Dinner in Honour of Chairman of State Affairs of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea Kim Jong-un”, no. 22.

- 26. “North Korea Recognises Breakaway of Russia's Proxies in East Ukraine”, Reuters, 14 July 2022.

- 27. “Joint Statement by Senior Officials of the United States, the Republic of Korea (ROK) and Japan on DPRK-Russia Cooperation”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Korea, 24 June 2024.

- 28. “North Korea Calls South Korea, US and Japan 'Asian version of NATO'”, Reuters, 30 June 2024.

- 29. “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Lin Jian’s Regular Press Conference on June 18, 2024”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 18 June 2024.

- 30. “Vilnius Summit Communiqué”, NATO, 11 July 2023.