You are here

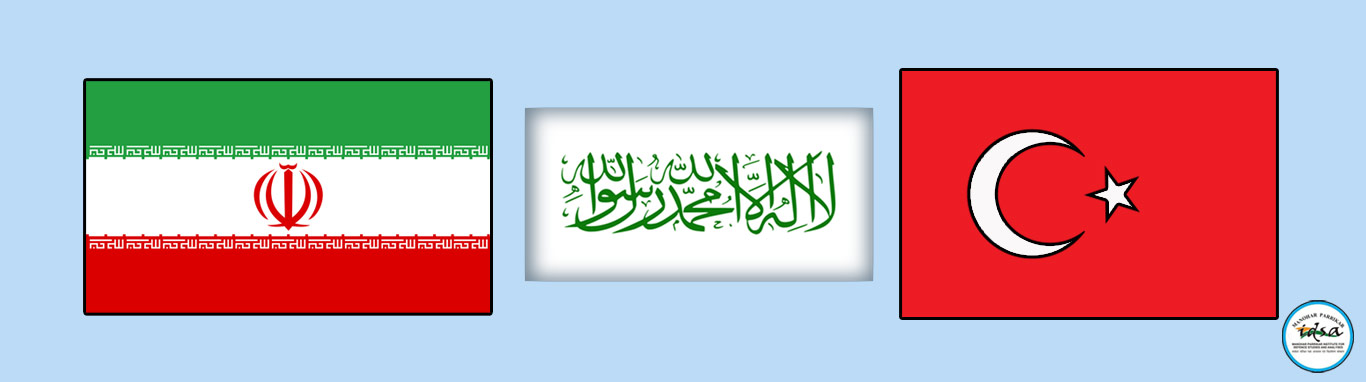

Turkish and Iranian Response to Upheaval in Afghanistan

The chaotic end of the US military mission has raised serious questions about the future of Afghanistan. The Taliban are back in the saddle leading to fears of Afghanistan turning into a regional hub for international terrorist groups. The disheartening scenes of frenzied Afghans gathered at the Kabul International Airport to escape in anticipation of the revival of the brutal Taliban rule has added to the international anxiety. Taliban’s public assurances of respecting the rights and freedom of women and minorities and not allowing Afghan soil to be used by terrorist organisations have not helped calm the nerves of either the Afghans or the international community.

The developments have wider regional implications forcing the neighbouring countries to adjust to the new realities. Russia, China, Pakistan, Qatar, Turkey and Iran are at the forefront of engaging the Taliban for a variety of reasons. Qatar that facilitated the US-Taliban talks and hosts the Taliban’s only international office is now among the closest allies of the Taliban. Russia and China have moved swiftly to engage the Taliban to neutralise any security threats and fill the vacuum created by the US departure. Pakistan has emerged as a key factor because of its historical links with the Taliban. On their part, both Turkey and Iran have expressed their willingness to engage the fundamentalist group now at the helm in Kabul. However, both countries have been cautiously optimistic in their initial reaction.

Iran has traditionally been an influential neighbour of Afghanistan based on strong historical ties and cultural linkages. However, Tehran’s latest moves are driven by its security interests including the need to manage the 921-kilometre border with Afghanistan to prevent refugee influx and smuggling of drugs and narcotics, and also issues such as water sharing, protection of Afghan Shia minorities, containing the Baluch insurgency and neutralising terrorist threats. Tehran developed contacts with the Taliban leadership in anticipation of the US exit, despite the sectarian divide and the antagonistic relationship of the past.

Turkish feelers to the Taliban are driven by Ankara’s ambition to expand its influence in the Islamic world and emerge as the leading interlocutor between the Taliban and Western powers. Ankara, for instance, was keen to host an intra-Afghan dialogue in April 2021, which eventually could not take place due to the Taliban’s refusal to attend.1 Besides geopolitics, Turkey has other interests including preventing the refugee influx and mitigating any security threats emanating from an unstable Afghanistan. Ankara is also eyeing potential reconstruction contracts in Afghanistan that can bolster the flailing image of the Erdogan government.

Broadly, three key issues are likely to determine the future course of Turkish and Iranian actions in Afghanistan in the short-to-medium term. Firstly, both are concerned about the refugee influx which can acquire a dangerous manifestation if Afghanistan witnesses further instability or descends into a civil war. Iran already hosts nearly 3.6 million Afghan refugees and according to some estimates, as of August 2021, nearly 5,000 Afghans are crossing over to the Iranian side every day.2 This presents a serious challenge for the struggling Iranian economy due to US sanctions and the impact of COVID-19. The dire economic situation has created internal strife in Iran with reports of sporadic protests coming from various parts of the country.

Turkey too is concerned about the refugee influx as the presence of nearly 4 million Syrian refugees has been a headache for the government grappling with the economic slowdown. The debilitating impact of COVID-19 notwithstanding, Turkey’s economy has been struggling to break out of sluggish growth over the past few years. Resultantly, there is rising anti-refugee sentiments among the Turks with frequent reports of violence against Syrian refugees.3 Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu has on several occasions reiterated his country’s inability to take more refugees and Ankara has begun reinforcing the border with Iran to prevent Afghans from attempting to enter the country.4

Secondly, security threats emanating from jihadi-terrorist groups including the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and al-Qaeda pose a challenge for Turkey and Iran. Due to their political and military involvements in Iraq and Syria and support in the fight against ISIS, both Iran and Turkey have been primary targets of the terrorist group. Given that the Taliban has publicly committed to not allow any terrorist groups to take shelter in Afghanistan and launch attacks outside, it makes sense for Iran and Turkey to engage and coordinate with the Taliban to mitigate the security threats.

Thirdly, the Turkish and Iranian reactions are driven by geopolitical ambitions. Iran, which is a revisionist regional power calling for an end to external involvement in regional affairs, sees the US withdrawal from Afghanistan as a sign of declining US interest in the region. It views the Taliban as an anti-American force, and hence, will be willing to work with it to advance Iran’s regional interests. President Ebrahim Raisi, for example, has termed the US exit from Afghanistan as a “military defeat” of the US and has underlined Iran’s willingness to work with the new dispensation in Kabul to establish “lasting peace” in the “brotherly” country of Afghanistan.5 In July 2021, Iran hosted a Taliban delegation led by Sher Mohammed Abbas Stanekzai, the deputy head of Taliban political office in Doha, along with representatives of the Ashraf Ghani government to explore possibilities of Iran playing a role in intra-Afghan talks.6 Nonetheless, Iran will face a dilemma if the Taliban rule leads to violence against Shia minorities in Afghanistan who have deep socio-cultural links with Iran.

For Turkey, the Taliban takeover presents an opportunity to expand its regional role in Southwest Asia. Turkey under the Justice and Development Party (AKP) has been following a revivalist “neo-Ottoman” foreign policy with the aim to acquire a leadership position in the Muslim world and emerge as a global middle power. Accordingly, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan first proposed the idea of a Turkish mission running the Kabul International Airport after the US withdrawal during a meeting with President Joseph Biden in June 2021.7 The proposal was intended to insert Turkey as a prominent external actor in the Afghan theatre, and as a way of mending relations with Washington. With the Taliban takeover, Ankara again reiterated its willingness to secure and run the airport. However, given the Taliban’s lack of enthusiasm, the proposal fell through with Qatar coming in to help the Taliban secure and run the airport.8 Nonetheless, Turkey is unlikely to give up and will try to develop close contacts with the Taliban. Ankara has an advantage because of its strategic relations with both Qatar and Pakistan, two of the closest allies of the Taliban. On August 11, for example, during a visit of Turkish Defence Minister Hulusi Akar to Islamabad, Prime Minister Imran Khan urged Turkey to take a larger responsibility in stabilising Afghanistan.9

The early reactions from Turkey and Iran underline their readiness to work with the Taliban to safeguard their interests and expand their regional influence. Both are also willing to work with other regional actors – Russia, China and Pakistan – to bring about a sense of normalcy in Afghanistan and to mitigate traditional and non-traditional security threats emanating from the country.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. Hamid Shalizi, “U.S.-backed Afghan Peace Conference in Turkey Postponed over Taliban No-show – Sources”, Reuters, 21 April 2021.

- 2. “Resettlement of Refugees Living in the Islamic Republic of Iran”, Background Note on Resettlement – July 2021, The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2 August 2021; and “External Update: Afghanistan Situation”, UNHCR Regional Bureau for Asia and Pacific, 16 August 2021.

- 3. “Turkish Capital Reels from Violent Protests Against Syrians”, BBC News, 12 August 2021.

- 4. Ali Kucukgocmen, “Turkey Reinforces Border to Block any Afghan Migrant Wave”, Reuters, 23 August 2021.

- 5. “President: US Military Defeat, Withdrawal from Afghanistan Should be an Opportunity to Restore Life, Security, Lasting Peace in Afghanistan”, Office of the President, Islamic Republic of Iran, 16 August 2021.

- 6. “Afghan Government Meets Taliban in Tehran: Iran”, The Hindu, 7 July 2021.

- 7. Md. Muddassir Quamar, “Outcomes of the First Biden-Erdoğan Meeting”, MP-IDSA Comment, 21 June 2021.

- 8. “Qatar in Talks with Taliban to Re-open Kabul Airport: FM”, Al Jazeera, 2 September 2021.

- 9. “Turkey, Pakistan to Work for Peace and Stability in Region”, Daily Sabah, 11 August 2021.