You are here

Iran Battling COVID-19

Summary: Iran is battling the COVID-19 pandemic amidst limited resources, a weak economy and a difficult political situation. Iran is the worst affected country in the West Asian region. While it is unlikely that the Iranian regime will be able to weather this crisis without the support of the international community, its efforts at seeking international support largely remain a work in progress. It is important that both the US and Iran grasp the urgency of international cooperation to address this global health crisis. Showing flexibility in addressing mutual concerns can also accelerate prospects for renewed negotiations between the two nations.

Summary: Iran is battling the COVID-19 pandemic amidst limited resources, a weak economy and a difficult political situation. Iran is the worst affected country in the West Asian region. While it is unlikely that the Iranian regime will be able to weather this crisis without the support of the international community, its efforts at seeking international support largely remain a work in progress. It is important that both the US and Iran grasp the urgency of international cooperation to address this global health crisis. Showing flexibility in addressing mutual concerns can also accelerate prospects for renewed negotiations between the two nations.

Since the outbreak of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Wuhan in December 2019, the world is on an unprecedented quest to find ways to deal with this global challenge. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has declared COVID-19 as a 'pandemic' with the virus now spread over 202 countries and regions, affecting every aspect of human life around the world.1 Although it is too early to predict how this global pandemic will pan out in the future, multiple international reports suggest an impending global economic slowdown. Countries which were already in the throes of economic problems are likely to be the hardest hit.

For the West Asian region, which has been confronting multiple security and economic challenges, COVID-19 could not have come at a possibly worse time, with profound implications for its people.

Today, Iran is the most severely affected country in West Asia with 73,303 confirmed cases and 4,585 deaths.2 For an already fractured economy battling tough American sanctions, COVID-19 has brought new challenges that has the potential to further undermine the stability of the Iranian economy.

In the present situation, four questions merit attention – How is Iran responding to the coronavirus crisis with limited resources at its disposal? Will the Iranian regime succeed in weathering this catastrophe? What are the political and economic implications for Iran? Will COVID-19 offer an opportunity for regional confidence building measures (CBMs), thereby paving the way for regional cooperation? And, will the coronavirus induced crisis ease existing Iran-United States (US) tensions?

Spread of COVID-19 in Iran

In the past, Iran had been able to manage its internal and external challenges. However, with the advent of COVID-19, the fight is now against an unknown enemy amidst limited resources, a weak economy and a difficult political situation. In this context, Coronavirus has severely hit the Iranian economy, society and regime. As on April 14, Iran reported 73,303 confirmed COVID-19 cases along with 4,585 deaths. Notably, the Iranian mortality rate of six per cent remains slightly higher than the global average of around five per cent even though there has been a recent spike in the recovery of patients, averaging 1,400 recoveries per day vis-a-vis the earlier average of 460.3 In total, 29,812 individuals have recuperated from the illness till date.

Iran reported its first case on February 19 in Qom, and the virus quickly spread thereafter to other parts of the country. This led to the cancellation of sports events, closing down of educational institutions and businesses, and prohibition on mass religious gatherings. However, instead of announcing a complete lockdown, the government only restricted travel and people-to-people contact ahead of the Nowruz celebrations.4 Even the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei cancelled his Nowruz speech.5 Notably, the government, in early February, had temporarily released more than 54,000 prisoners6 followed by more releases in March in order to minimise the risk of mass contagion in its overcrowded prisons.

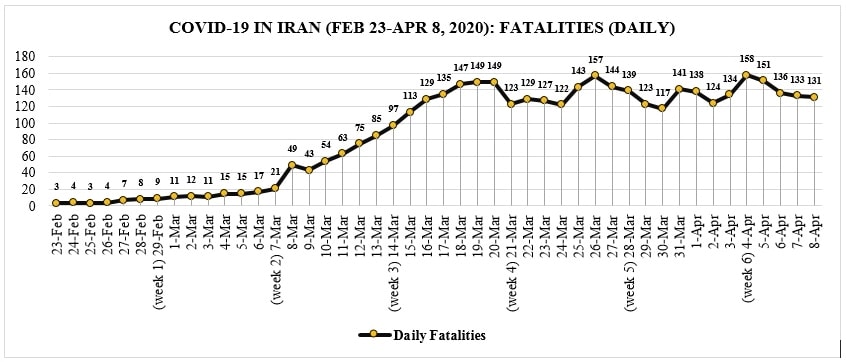

Tehran has witnessed the highest number of cases, followed by Isfahan, Qom, Mazandaran, Gilan, Khorasan Razavi, Markazi, Semnan, Yazd, Qazvin and Markazi. After increasing steadily for two weeks, the daily death count spiked in the third and the fourth weeks with casualties peaking on April 4. Since then, the daily death count has seen a declining trend with 131 fatalities being registered on April 8 (see figure below).

Source: Based on data gathered from Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA), Mehr News Agency and Al Jazeera.

Several eminent people have succumbed to the virus s far. They include Ali Larijani7 (Speaker of Parliament), Ali Akbar Velayati8 (member of Expediency Council and close aide of Khamenei), Eshaq Jahangiri9 (Vice-President of Iran), and Iraj Rabiei10 (Deputy Minister of Health).11

Regime’s Response

The rapid spread of COVID-19 and the resulting mass casualties, including among high profile officials, indicate a somewhat casual initial approach of the regime.

On February 23, the Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL), acting on the advice of Supreme Leader Khamenei, created the first sample of a COVID-19 test-kit.12 The Ministry along with various production units of the Armed Forces also started manufacturing masks, medical equipment and other machinery needed to combat the virus.13 On March 30, the Defence Ministry unveiled a new generation test kits which can detect COVID-19 within three hours.14 A National Committee on Combating Coronavirus was established to work in conjunction with the Ministry of Health.

On the economic front, the government has initiated steps to lessen the blow on the economy by announcing several financial packages and delaying tax collection. In doing so, the regime has attempted to balance the prevailing economic crisis with the necessity to combat the spread of the pandemic. This sentiment was echoed in President Hassan Rouhani’s statement that “he had to weigh protecting the country's sanctions-hit economy while tackling the worst outbreak in the region.”15 President Rouhani announced the decision to allocate 20 per cent of the budget to fight COVID-19.16 He has also sought US$ 1 billion from Iran’s National Development Fund to cover the potential budgetary deficit.17

Additionally, the Iranian Government spokesperson Ali Rabiei has announced a relief package of €21.3 billion to help the “vulnerable families and the private sector” directly impacted by the pandemic.18 He added that around €16 billion would be given as loans to businesses where employers have retained their workers despite taking a hit on their profits.19 The government will also cover the medical expenses of all patients undergoing treatment.20

While Iran has refused to accept any aid offered by the US to fight this crisis, it has urged21 the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for an emergency funding of US$ 5 billion. Notably, the US has opposed this Iranian request.22 Meanwhile, Iran has received widespread international support, including from WHO23, China, France Turkey and Japan24, Qatar25 and Turkmenistan26. China has pledged around 20,000 test kits.27 Japan has announced US$ 23.5 million in medical aid to Iran. Whereas, other countries such as Qatar and Turkmenistan have provided support in the form of medical equipment.

In a positive development, the first transaction of the much-awaited special purpose vehicle – INSTEX28– was confirmed by Germany.29 This is likely to provide the much-needed relief for Tehran, particularly in the field of humanitarian assistance. However, the impact of INSTEX is likely to be limited. The Rouhani Government has already expressed scepticism in this regard by attributing the move as “insufficient”.30

The government has also approached the international community to lift sanctions.31 President Rouhani has led the initiative by writing letters to several world leaders.32 However, Tehran has received limited support with only a few countries supporting its call for assistance. Notably, China and Pakistan have vociferously supported Iran with Prime Minister Imran Khan labelling the sanctions as “cruel and unfair” and calling for their lifting on “humanitarian grounds”.33 Meanwhile, on March 24, the Iranian Government asked Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) to leave Iran, amid charges of espionage.34

Fallout of COVID-19

The Iranian economy, already reeling under the impact of debilitating American sanctions, with runaway inflation in the prices of every essential commodity, has been the biggest casualty of the spread of COVID-19.

Today, the Iranian economy is struggling to survive in, arguably, the toughest period since the revolution. With US sanctions on Iran’s oil exports cutting off Tehran’s key source of revenue, the country has struggled to purchase even critical items from abroad needed to tackle the pandemic. Lamenting the serious situation facing his country, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif noted, “Iran is the only country that does not have access to all of its resources to protect its citizens; Iran is the only country that cannot easily buy medical equipment and supplies in the face of disease” and the “combination of sanctions and coronavirus is a more dangerous enemy and a more serious complication which makes corona bolder and makes crisis management decisions more difficult.”35

For a country in the throes of serious internal and external pressures, the explosion of COVID-19 cases is another blow to the Iranian regime in its endeavour to manage its weak economy and a divided political system. Notably, the year 2020 has been a challenging one for the regime. The killing of Gen. Qassem Soleimani and the downing of Ukrainian civilian jet was followed by parliamentary elections that strengthened the position of hardliners in the management of national affairs.36 Meanwhile, a massive invasion of locusts has resulted in the destruction of vast swathes of crops in the southern parts of the country. Moreover, the inclusion of Iran in the international Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) blacklist on money laundering and terror financing will further undermine its efforts to seek international financing for its businesses. The dramatic decline in both oil prices and Iran’s oil exports have further increased the economic burden.

Undoubtedly, the economic challenges faced by Iran are likely to be the most difficult to overcome. While it is unlikely that the Iranian regime can weather this crisis without the support of the international community, its efforts at seeking international support remain a work in progress. Meanwhile, Iran’s ability to control and support its regional assets in Iraq, Syria, Yemen and Lebanon is likely to be diluted in future. This may undermine Iran’s overall control and influence in the region.

A key issue worth examining is the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on Iran-US tensions. So far, the US has continued with its policy of applying “maximum pressure” and introducing fresh sanctions against Iran. The new sanctions will not only further isolate Iran diplomatically but also blacklist companies in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), China, Hong Kong and South Africa from engaging in petrochemicals trade with Tehran. The US has also reportedly blocked Tehran’s efforts to secure an IMF loan to fight the pandemic. Notably, the IMF has announced a series of emergency loans to several of Iran’s neighbours including India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. At this stage, it is not clear if the IMF has blocked or is yet to process the Iranian loan application. Nonetheless, the European Union (EU) has said that it will support the Iranian application.

The COVID-19 pandemic has so far not led to any reduction in US-Iran tensions. In early April, the chief of staff of the Iranian armed forces cautioned that any US provocation will be met with the “fiercest” possible response after President Trump accused Iran of preparing a “sneak attack” against American forces in Iraq.37 However, as the US administration gets completely immersed in managing the domestic spread of COVID-19, its focus on Iran may get diminished in future. Notably, the damage caused to the Iranian regime’s reputation and popularity, on account of its perceived inability to navigate the multiple crises, may serve the American game plan for a regime change and force the country to renegotiate the nuclear deal.

Today, the COVID-19 related disruptions reveal the magnitude of challenges that Iran has hitherto faced. Given the nature and scale of this unknown enemy, even the famed Iranian resilience is unlikely to be sufficient to tackle the crisis without the easing of sanctions and international support.

Conclusion

While COVID-19 has exposed every country in the West Asian region to a new set of challenges, Iran remains the worst affected country. Its problems are much more severe due to the existing economic sanctions and the continued effort of the Donald Trump administration to inflict maximum damage on the Iranian economy through its “maximum pressure” policy. Arguably, the COVID-19 crisis has brought Iran to a new turning point where the future course of developments - both internal and external – will depend on the following factors:

- First, the Iranian regime’s ability to regain the lost trust of its people by devising a new social contract that provides them with better health care facilities to fight the virus and effectively addresses people’s economic hardships.

- Second, at the regional level, the Iranian regime’s constructive use of the present opportunity as a CBM to fight this deadly pandemic along with rest of the regional countries.

- Third, at the global level, the ability of countries friendly to Iran such as the EU, Russia and China to help the Iranian regime in its battle against COVID-19 while simultaneously persuading the US to ease economic sanctions at this critical moment, thereby prioritising humanitarian concerns over geopolitics.

- Finally, the extent of accommodation between the Iranian regime and the Trump administration with respect to each other’s concerns, keeping in view the seriousness of this pandemic and its impact on the larger community in West Asia and beyond. While many anticipate that present hardships may push the Iranian regime towards concluding a new agreement with the US, an imminent conclusion of such an agreement is unlikely. It is important for both nations to grasp the urgency of international cooperation to address this global health crisis. Showing flexibility in addressing mutual concerns can certainly accelerate the possibility of such an agreement.

Given the rapid spread of COVID-19 in Iran and the increased potential of contagion spilling over into the neighbouring countries and regions, assistance must be rendered to Iran by countries like India, Russia, Japan, China and Europe. It is also likely that Tehran will seek to counter renewed US sanctions by adopting a high-risk strategy that can be detrimental to the ongoing efforts against the spread of the virus.

Nevertheless, the COVID-19 crisis has exposed the limited options available to the Iranian regime. On April 5, President Rouhani announced the opening of low-risk jobs and businesses in provinces from April 14 and Tehran from April 20 onwards. While this carries an inherent element of risk, the Iranian economy cannot afford to remain shut for long due to the twin challenge of COVID-19 induced disruptions and American economic sanctions. Given the global impact of the pandemic, perhaps, the need of the hour is to devise cooperative mechanisms not just bilaterally between the US and Iran but also regionally in the battle against COVID-19.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. As of April 14, 2020, there are 1,930,780 confirmed cases and 120,450 deaths globally, as a result of COVID-19. The most severely affected countries around the world are the US, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, China, Iran, UK and Turkey, which together account for nearly 1,489,826 confirmed cases (77 per cent) and around 101,103 deaths (84 per cent). See Coronavirus Resource Centre, Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE), Johns Hopkins University, April 14, 2020 (Accessed April 14, 2020).

- 2. Ibid.

- 3. Ibid.

- 4. “‘No Lockdown’ Says Rouhani As Nearly 14,000 Iranians Contract COVID-19”, Radio Farda, March 15, 2020.

- 5. “To counter the Corona outbreak, there will be no New Year speech”, Khameni, March 10, 2020.

- 6. “Coronavirus: Iran temporarily frees 54,000 prisoners to combat spread”, BBC News, March 03, 2020.

- 7. “Iran's Majlis speaker tests positive for coronavirus”, Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA), April 02, 2020.

- 8. “Top Adviser to Iran’s Supreme Leader infected with coronavirus: Tasnim”, Reuters, March 13, 2020.

- 9. “Coronavirus: Iran's first vice president Jahangiri infected”, Middle East Eye, March 11, 2020.

- 10. “Coronavirus: Iran's deputy health minister tests positive as outbreak worsens”, BBC News, February 25, 2020.

- 11. Around 23 other lawmakers and several other clerics have died due to COVID-19. Notable individuals include Hashem Bathaie Golpayegani (Advisor to Supreme Leader) and Mohammad Mirmohammadi (senior member of the Expediency Council). See John Henley, “Coronavirus: Iran steps up efforts as 23 MPs said to be infected”, The Guardian, March 03, 2020.

- 12. “Production of the first coronavirus detection kit in Iran”, Sputnik News, February 23, 2020.

- 13. “Defense Industries plant produces masks & protective gowns for medics”, IRNA, March 29, 2020; and “IRGC Comdr: Basij produces 3 million masks daily”, IRNA, March 28, 2020.

- 14. “MoD mass produces test kit able to detect COVID-19 in 3 hours with 98% accuracy”, Mehr News Agency, March 30, 2020.

- 15. “As Iran coronavirus deaths rise, Rouhani hits back at criticism”, Al Jazeera, March 29, 2020.

- 16. “Iran to use 20% of state budget to fight coronavirus”, Reuters, March 29, 2020.

- 17. “Iran's Government Withdrew Money From National Reserve To Pay Salaries - Lawmaker”, Radio Farda, April 05, 2020.

- 18. “Iran announces COVID-19 relief package”, IRNA, March 29, 2020.

- 19. Ibid.

- 20. Ibid.

- 21. “Iran asks IMF for $5 billion emergency funding to fight coronavirus”, Reuters, March 12, 2020.

- 22. Bryant Harris, “Intel: US comes out against emergency COVID-19 IMF loan for Iran”, Al-Monitor,April 07, 2020.

- 23. “Iran receives 5th consignment of coronavirus test kits”, IRNA, February 28, 2020.

- 24. “Iran appreciates Japan's $ 23.5m medical aid”, IRNA, March 13, 2020.

- 25. “Qatar sends 2nd anti-COVID19 consignment to Iran”, IRNA, March 20, 2020.

- 26. “Turkmenistan donates medical safety-mask shipment to Iran”, IRNA, March 19, 2020.

- 27. “China to provide Iran with 20k coronavirus test kits, says MFA Spox,”, IRNA, February 27, 2020.

- 28. INSTEX is a special-purpose vehicle (SPV) launched in January 2019 by E3 (France, Germany, and the UK) to facilitate non-USD transactions with Iran.

- 29. “Germany confirms first INSTEX transaction”, IRNA, March 31, 2020.

- 30. “Rouhani says launching INSTEX positive, insufficient move”, IRNA, April 06, 2020.

- 31. “Iran hopes for partial sanctions relief amid epidemic”, Al-Monitor, March 25, 2020.

- 32. “US sanctions 'severely hamper' Iran coronavirus fight, Rouhani says”, Reuters, March 14, 2020.

- 33. “Pakistan PM asks Trump to lift Iran sanctions”, IRNA, March 22, 2020.

- 34. “Iran tells Doctors Without Borders to leave despite worsening epidemic”, Al-Monitor, March 24, 2020.

- 35. “World will fail again if pandemic fails to stop unilateralism, Zarif warns”, Tehran Times, March 30, 2020.

- 36. The frustration of the population was reflected in the February 2020 elections to the Majlis, with the national participation rate falling to 42 per cent nationally, and 22 per cent in Tehran. This was the lowest voter turnout since the Islamic revolution in 1979.

- 37. “Iran monitoring US military moves in region”, Mehr News Agency, April 02, 2020.