You are here

| Title | Date | Date Unique | Author | Body | Research Area | Topics | Thumb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhutan’s Graduation from LDC: Opportunities and Challenges | January 11, 2024 | Sneha M |

Bhutan, known for its unique developmental model centered on collective happiness (gross national happiness), has achieved yet another milestone. By the end of 2023, Bhutan joined the group of developing middle-income economies by foregoing its title as a ‘Least Developed Country’ (LDC).1 Attaining non-LDC status signifies a notable achievement in the developmental journey of landlocked nations. However, the ongoing reduction of international support measures associated with this status presents potential challenges for Bhutan as the country continues to work towards sustaining its integration into the global economy. UN Criteria and Evaluation ProcessThe United Nations (UN) classifies LDCs as nations characterised by low-income levels and substantial structural barriers hindering sustainable development. This category of LDCs was formally established in 1971 through General Assembly Resolution 2768 (XXVI). The decision to include or graduate a country from the LDC list is determined by the UN General Assembly, relying on recommendations from the Committee for Development Policy (CDP) and subsequently approved by the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). The CDP conducts triennial reviews of the LDC list, which involves assessing the eligibility of countries for inclusion or graduation from the LDC category. This process aims to provide targeted assistance to the most underdeveloped nations within the developing world. Currently, the UN recognises 45 nations as Least Developed Countries (LDCs).2 Among them, nine are situated in Asia, three in the Pacific, one in the Caribbean, and 33 in Africa. The LDCs undergo evaluation based on three benchmarks—Gross National Income (GNI) per capita, Human Assets Index (HAI) measuring health and education outcomes, and Economic and Environmental Vulnerability Index (EVI).3 To be promoted from LDC, a nation must meet the graduation requirements for two of the aforementioned criteria in two consecutive triennial review periods of the CDP. No matter how well a nation does in the other two criteria, it may be recommended for graduation if its GNI per capita increases to twice the predetermined level. In sum, achieving these goals may necessitate the implementation of a combination of strategies. These could encompass stimulating economic growth through infrastructure investments, improving governance, diversifying the economy, addressing environmental concerns, and making substantial investments in human development. Charting Bhutan’s Economic CourseIn 1971, Bhutan joined the initial cohort of LDCs.4 Over subsequent decades, the Himalayan Kingdom has undergone a remarkable transformation, experiencing substantial economic growth and witnessing an overall enhancement in the living standards of its populace. Bhutan's economic growth since 1961 has been marked by a trajectory of development plans. Initiated with India's support during the first and second Five Year Plans (1961–1972), Bhutan laid the foundation for its economic journey in 1961. The subsequent decades witnessed steady growth, prominently influenced by development in the hydropower sector. In the 1990s and 2000s, the opening of Chukha Hydropower Plant played a pivotal role. In the 2010s, the focus on sustainable development and diversification of sectors such as tourism contributed to continued economic resilience. Moreover, from 2010 to 2019, Bhutan's economy exhibited robust expansion, boasting an average annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth exceeding 5 per cent, resulting in significant reductions in poverty. Bhutan has achieved remarkable advancements, including substantial progress in education, with an estimated overall literacy rate of approximately 66 per cent in 2018. The provision of electricity has become nearly universal, reaching 98 per cent coverage in 2017, and basic access to potable water services extended to about 97 per cent of the population in the same year. The country's growth has resulted in a remarkable decline in the national poverty rate, dropping from 23.2 per cent in 2007 to 8.2 per cent in 2017. In terms of the Human Development Index (HDI), Bhutan scored 0.654 in 2019, surpassing other Asian LDCs.5 Regardless, the February 2021 Monitoring Report by the UN CDP underscored Bhutan's exceptional performance, with GNI per capita growth estimated at USD 2,982, three times the graduation threshold of USD 1,222. Additionally, Bhutan's Human Assets Index (HAI) score exhibited substantial improvement, reaching 79.4 (compared to the required score of 66). Despite excelling in GNI per capita and HAI, Bhutan faces challenges in meeting the Economic & Environmental Vulnerability Index (EVI) criterion, with an EVI of 25.7, below the threshold of 32.6 Nonetheless, this positions Bhutan as one of the fastest-progressing non-oil exporting LDCs. Despite these challenges, there has been a noteworthy rebound in economic growth, with projections indicating an approximate 4.2–4.7 per cent expansion since the financial year 202223.7 In FY 2022–23, the economy again grew by 4.6 per cent, driven by reopening of the borders for tourism in September 2022. The industry sector expanded by 5.1 per cent, with growth in construction and manufacturing, while the services sector grew by 5 per cent, creating more jobs, especially in transport and trade services.8 Prospects and PredicamentsBhutan's exit from LDC carries significant promise across multifaceted dimensions of its development trajectory. Economically, this transition opens new doors for the nation, ushering in opportunities that have the potential to ignite robust growth and development. The improved economic conditions that accompany such a shift may act as magnets for foreign investments, encouraging diversification of industries and enhancing Bhutan's recognition on the global stage. In addition, the anticipated focus in the 13th Five Year Plan (FYP) on infrastructure development holds the promise of increased efficiency and connectivity.9 This could manifest through the creation of advanced transportation networks, energy infrastructure, and improved communication systems, all of which play crucial roles in fostering economic vitality. As Bhutan asserts greater autonomy in decision-making post graduation, a noticeable decrease in reliance on foreign aid could be anticipated. This transition empowers the nation with increased control over its policies and resources, fostering a trajectory towards a self-reliant and robust economy. Importantly, the positive effects extend beyond economic dimensions, encompassing notable improvements in human development, particularly in healthcare, education, and overall living standards. However, amidst these promising prospects, it is crucial to underscore the importance of responsive governance and strategic planning. Navigating the challenges associated with such a transformative phase necessitates prudence and vigilance to prevent potential economic pitfalls in the years to come. Grappling with various challenges and developmental constraints, Bhutan has significant economic vulnerabilities exacerbated by natural disasters. Its small and vulnerable economy, characterised by mountainous terrain, sparse population, limited industrial development, constrained global market access, and a narrow product range meeting international standards, faces predicaments upon graduating from its LDC status. The graduation will impact LDC-specific international support measures (ISM) in international trade, official development cooperation (ODA), and climate resilience support. The Himalayan Kingdom currently benefits from LDC-specific preference schemes, such as the Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) providing tariff exceptions, and duty-free and quota-free (DFQF) market access in the European Union (EU) and Japanese markets. Regional trading agreements, like the South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA), also offer preferential market access. However, exiting LDC status implies the erosion of these preferential trade agreements, resulting in increased tariffs and negative implications for export and economic diversification efforts.10 Bhutan's development success has historically relied on natural resources, particularly hydropower generation and tourism. Despite the swift rise in per capita income, reflected in the evolution of GNI per capita, there are concerns about structural impediments hindering economic diversification. Hydropower, as a capital-intensive sector, significantly contributes to the GDP, fostering the growth of energy-intensive industries. In the realm of international trade, Bhutan currently stands outside the World Trade Organization (WTO) but is actively considering membership and may join shortly. As a non-WTO member, Bhutan is not bound by WTO provisions, lacking the protective cover of multilateral rules. The potential benefits of WTO accession, including facilitating export expansion, must be weighed against challenges, heightened scrutiny, and the necessity to undertake commitments, especially considering the capacity constraints of LDCs acknowledged by WTO members. Nonetheless, the predominant worry revolves around the potential consequences of climate change on Bhutan's economic advancement, presenting a risk to the achievements made through persistent efforts. ConclusionFor Bhutan to sustain its growth and development trajectory post graduation, a comprehensive set of policies is imperative to tackle the multifaceted challenges inherent in its development path. As a small, vulnerable, landlocked nation heavily reliant on a limited range of export commodities, Bhutan remains exposed to economic vulnerabilities and natural disasters. The country's ability to continue its developmental journey after graduation hinges significantly on the graduation process itself, emphasising the necessity of a seamless transition. A pivotal aspect of Bhutan's transition strategy should center on alleviating structural challenges, enabling the effective implementation of 13th FYP and cultivating the resilience required for navigating the post-LDC status environment. In sum, the transition should address vulnerabilities through economic diversification, developing productive capacities for structural transformation, and bolstering disaster management to enhance economic and natural disaster resilience.

|

South Asia | Bhutan, United Nations | system/files/thumb_image/2015/unnamed.jpg | |

| Beyond Borders: The Urgent Case for Global Cooperation in Cyber Defence | January 04, 2024 | Cherian Samuel |

Over the past year, the cyber conflict between Ukraine and Russia has captured much attention. Yet, a similarly critical situation has unfolded in the China–Taiwan theatre, where cyberattacks have significantly escalated. Reports from Google's threat analysis division and Microsoft security have confirmed this uptick, pinpointing that these incidents predominantly target critical sectors like energy systems, electrical grids, and communication networks. The semiconductor industry has not been spared either. A report by the cybersecurity company Fortinet reveals a staggering figure of 412 billion attack events detected in Asia-Pacific in the first half of 2023, with Taiwan bearing the brunt at 22.48 billion, marking an 80 per cent increase from the year prior. Alongside espionage efforts, Taiwan has faced Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) and ransomware attacks. Further intensifying the situation are the misinformation campaigns aimed at undermining public trust in Taiwan's government and stoking societal confusion. India has also been at the receiving end of misinformation aimed at Taiwan. A recent rumour claiming that the Taiwanese government was bringing in as many as 100,000 migrant workers from India went viral on social media in Taiwan. Though refuted by the Taiwan government, various social media pages operated by the Taiwan government were spammed with bot messages designed “to create social panic and spark tension between Taiwan and India”.1 In defence, Taiwan has fortified its cyber capabilities by establishing its Information Communication Electronic Force Command in 2017, consolidating various military units into one formidable force of over 6,000 personnel. The latest National Cybersecurity program, the sixth of its kind since 2001 and running until 2024, reflects Taiwan's commitment to strengthening its cyber defences—protecting crucial infrastructure, enhancing cyber skills, increasing information security, and supporting the private sector in safeguarding its operations. A key goal is to position Taiwan as a hub for cyber research and development.2 Taiwan's role in global cyber stability is underscored by its critical position in the electronics supply chain. Taiwan is the sixth-largest electronics exporter globally, with electronics exports valued at US$ 94.8 billion in 2021, representing a 3.9 per cent share of the global electronics market. Taiwan is known for its semiconductor manufacturing capabilities, with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) alone having a 56 per cent global market share. Taiwan has had a long-standing relationship with the United States, which has acted as a security guarantor for the island nation through the Taiwan Relations Act passed by the US Congress in 1979. Its security has acquired further salience as it became a technological powerhouse over the years, making it more vulnerable to cyber attacks from China that considers reunification of Taiwan with the mainland as a major goal and has used cyber, first as a means of espionage, and now increasingly, for destructive attacks on the networks of countries it is hostile to. In its 2023 annual report to Congress on Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, the US Department of Defense noted that China could potentially use its cyber capabilities as part of a range of campaigns designed to coerce Taiwan. These campaigns may include cyberspace operations, blockade, and kinetic actions with the goal of compelling Taiwan to unify with China or to bring Taiwan's leadership to the negotiation table on terms favourable to the People's Republic of China (PRC). Cyber attacks had notably increased after Speaker Nancy Pelosi led a congressional delegation to Taiwan in August 2022 and are up 80 per cent from the same period in 2022.3 In April 2023, US lawmakers introduced the Taiwan Cybersecurity Resiliency Act, which would require the US Department of Defense to expand cybersecurity cooperation with Taiwan, calling for cybersecurity training exercises with Taiwan, joint efforts to defend Taiwan’s military networks, infrastructure, and systems, and leveraging US cybersecurity technologies to help defend Taiwan. The proposed legislation currently awaits further discussion in the Committee on Foreign Relations. Taiwan has also sought to share expertise it has acquired from responding to these attacks but is constrained by the limits of its participation in international organisations. It is however a member of the Asia Pacific Computer Emergency Response Team (APCERT) where it has been a part of the Steering Committee and the convenor of Training Working Group. Taiwan and the US have also established a Global Cooperation and Training Framework (GCTF) platform to capitalise on Taiwan’s expertise and experience to address global issues of mutual concern and assist other countries in their capacity building efforts. The other countries partnering in the framework are Japan and Australia. The GCTF has facilitated more than 63 workshops, engaging over 7,000 attendees from 126 countries, demonstrating Taiwan's commitment to sharing its cyber defence expertise and aiding in international capacity building. Most recently, the GCTF, with support from the US Embassy, held a workshop in New Delhi on 11 December 2023 with the aim of improving co-ordination and enhancing crisis response capabilities.4 The other aspects discussed, including AI, cyber crime prevention and critical information infrastructure protection, are also of utmost priority since the threats in these areas are moving faster than governments can respond individually. The growing instability in the international system which is manifested most in cyberspace underscores the urgency for robust defence mechanisms and international cooperation in cybersecurity with all like-minded countries to shield critical infrastructure and prevent systemic disruptions.

|

Strategic Technologies | Cyber Security, Cyberspace | system/files/thumb_image/2015/tdf-banner.jpg | |

| MONUSCO's Early Withdrawal and the Future of UN Peacekeeping in Africa | January 02, 2024 | Rajeesh Kumar |

On 19 December 2023, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) adopted Resolution 2717 to end its 24-year-old peacekeeping mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The resolution outlines a comprehensive disengagement plan for the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO), comprising three phases to gradually transfer responsibilities from MONUSCO to the Government of the DRC by December 2024.1 The UNSC decision was prompted by the DRC’s earlier request for the Mission's withdrawal. As the UN's longest-standing peacekeeping mission with a robust mandate faces a turbulent exit, it is crucial to ask what its critical failings were and what the UN can learn from them. MONUSCO in DRCMONUSCO commenced its peacekeeping mandate in the DRC, aiming to stabilise the nation torn by internal conflicts and political instability. Established in July 2010 by UNSC Resolution 1925, MONUSCO succeeded an earlier mission known as MONUC (United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo), initiated in 1999.2 This peacekeeping operation in the DRC became one of the longest-standing and most extensive UN missions globally, involving multifaceted objectives encompassing security, political stability, protection of civilians, and promoting human rights and development. In its initial years, MONUSCO deployed approximately 20,000 troops and played a crucial role in reducing the presence of foreign rebels in the DRC. Over its two-and-a-half-decade presence in the DRC, MONUSCO navigated complex challenges marked by internal strife, armed rebellions, regional tensions, and humanitarian crises. Within a few years after its establishment, MONUSCO achieved significant milestones, including disarming Congolese ex-combatants, repatriating foreign combatants, facilitating the return of Congolese refugees, and releasing children from armed groups.3 However, despite concerted efforts, MONUSCO faced persistent hurdles in achieving its mandates due to intricate and protracted nature of the conflicts, resource limitations, and political complexities. One of the contentious facets within the MONUSCO was establishing the Force Intervention Brigade (FIB) in 2013, an offensive military unit operating within the peacekeeping framework.4 The core objective of the FIB centred on curbing the expansion of armed groups, neutralising their impact and disarming them, thereby enhancing state authority and civilian security in eastern DRC to facilitate stabilisation efforts. DRC has suffered immeasurable losses, with an estimated 6 million lives lost in the last two decades.6 It also faces the largest internal displacement crisis in Africa, with ongoing violence forcing 5.8 million people—over half of them women—to flee their homes. Since June 2022, over 600,000 people have been displaced due to escalating violence.7 In 2023, approximately 10 million people in the DRC required aid amid the turmoil.8 This dire situation fuelled widespread resentment against MONUSCO, prompting calls, including from the DRC president, for its withdrawal.9 Anti-MONUSCO Protests and Attacks against PeacekeepersSince July 2022, DRC has seen a series of protests against MONUSCO. Attacks on UN peacekeepers surged, with over a dozen peacekeepers killed in one of the deadliest assaults against peacekeepers in recent history.10 More than 50 protesters died demanding the UN's withdrawal, blaming its inability to control rebel groups causing lethal attacks in the east.11 In November 2022, civilians targeted a UN peacekeeping convoy in eastern Congo, highlighting ongoing tensions. Also, a UN helicopter was attacked on 5 February, further underscoring the challenging situation faced by the mission in the region.12 Protests against MONUSCO in the DRC are not new. For instance, in 2019, following the ADF's atrocities in North Kivu, which MONUSCO could not prevent, large-scale protests against the UN mission erupted. However, this recent series of protests stands out due to its scale and the level of violence involved. Moreover, political elites also joined in criticising MONUSCO, intensifying pressure on the UN mission in the DRC. The International Peace Institute's 2022 report highlights increased disinformation about MONUSCO in the DRC, worsening negative sentiments towards the mission.13 Similarly, a recent survey revealed that nearly 45 per cent of Congolese want MONUSCO to leave the country immediately.14 This poses significant concerns regarding the future of peacekeeping missions in the continent. Future of UN Peacekeeping in AfricaAfrica has hosted the highest number of UN peacekeeping missions, accounting for nearly 47 per cent of all missions worldwide. The continent has been historically plagued by conflicts, civil wars, and humanitarian crises, making peacekeeping missions essential for regional and global stability. Despite many setbacks, UN missions helped end insurgencies, support elections and build peace in many African countries. However, growing resentments against UN missions raise serious concerns about the peacekeeping missions' effectiveness and long-term impact in the continent. The protests and premature withdrawal of troops indicate the crisis confronting UN peacekeeping operations in Africa. Since 1948, more than 4,300 UN personnel have lost their lives in peacekeeping missions, with over 1,000 falling victim to targeted attacks, predominantly in Africa.15 Since 2013, the Central African Republic (CAR), Mali, and the DRC have witnessed the highest number of attacks against peacekeepers.16 The UN mission in Mali (MINUSMA) is by far the most dangerous mission for peacekeepers, with 310 fatalities resulting from malicious acts from 2013 to 2023.17 The Security Council terminated the mission in June 2023, and peacekeepers exited the country without achieving their mandate. The African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID) also encountered opposition from political elites and exited without fulfilling its mandate.18 This peacekeeping crisis revolves around two main issues: first, concern about the erosion of core UN peacekeeping principles, leading to peacekeepers becoming parties in the conflicts they aim to resolve. Second, the missions' limited operational effectiveness, especially combating non-traditional threats like terrorism. These issues were evident in CAR, DRC and Mali, where peacekeepers were tasked with peace enforcement mandates. Further, most peace operations lack the necessary resources and training for counter-terrorism tasks. Peacekeepers, typically underfunded and undertrained, lack the specialised equipment, skills, and intelligence essential for effective counter-terrorism efforts. Hence, it becomes crucial for peacekeeping to adapt and evolve to address the challenges of the present era effectively. MONUSCO's closure marks the end of a significant era for large-scale UN peacekeeping missions in Africa. Its exit signifies a reduced UN presence on the continent compared to previous years. This situation might lead host governments to seek other security partners, including private military companies. For instance, Mali and the CAR extended invitations to the Wagner Group to operate within their countries.19 Likewise, in 2022, the DRC also opted for the involvement of private military contractors to intensify operations in the eastern regions.20 These instances collectively suggest a bleak outlook for the future of UN peacekeeping in Africa, highlighting the urgent need for a comprehensive restructuring of the UN's approach in the region. India recently proposed the establishment of clear, realistic mandates for peacekeeping and effective communication strategies involving local stakeholders. As the increased robustness of mandates has proven ineffective, there is a need to explore alternative solutions.21 As a significant Troop Contributing Country (TCC), India emphasises fostering trust and cooperation between mission leadership and host states to address acts against peacekeepers. India's proactive initiatives, mainly promoting accountability for crimes against peacekeepers, underscore essential areas requiring improvement.22 In light of the persisting challenges that extensive stabilisation missions face in achieving lasting peace in Africa, there is a growing rationale for the UN to consider shifting towards more traditional and narrowly focused peacekeeping missions. It would also enable the UN to maintain a clearer and more distinct role as a neutral mediator in conflicts, thereby rebuilding trust among the host governments and the local populations. This recalibration could lead to a more targeted and efficient use of resources and personnel.

|

Africa, Latin America, Caribbean & UN | UN Peacekeeping, United Nations, Congo, MONUSCO | system/files/thumb_image/2015/ind-un-digital-technology.jpg | |

| India`s Approach to West Asia: Trends, Challenges and Possibilities | Sujan R. Chinoy, Prasanta Kumar Pradhan |

About the BookThis volume provides perspectives of scholars from India and West Asia on several bilateral issues of concern, challenges and scope for further cooperation. The authors contend that a convergence of interests between India and West Asian countries across numerous domains, coupled with India`s escalating stakes in the region, and the growing recognition among West Asian nations of India`s burgeoning economic and political influence, stand as key drivers underpinning the India-West Asia relationship. Furthermore, they have underscored that under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India’s West Asia policy has undergone a major transformation. About the EditorsAmb. Sujan Chinoy is the Director General of the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA), New Delhi since 2019. A career diplomat from 1981-2018, he held several important diplomatic assignments, including as Ambassador to Japan and Mexico. A specialist on China, East Asia and politico-security issues, he anchored negotiations and developed confidence-building measures (CBMs) with China on the boundary issue from 1996-2000. On deputation to the National Security Council Secretariat (NSCS) from 2008-2012, his expertise covered external and internal security issues, particularly South Asia and the extended neighbourhood of the Indo-Pacific. Among his diverse foreign postings, he also served as Counsellor (Political) in the Embassy in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. He is the Chair of the Think20 engagement group for India`s G20 Presidency and a Member of the high-powered DRDO Review Committee. Dr. Prasanta Kumar Pradhan is a Research Fellow and Coordinator of the West Asia Centre at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA), New Delhi. He holds a doctorate degree from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Since joining MP-IDSA in 2008, he has been researching on foreign policy, security and strategic issues in West Asia, and India`s relationship with West Asia and the wider Arab world. Dr. Pradhan is the author of India and the Arab Unrest: Challenges, Dilemmas and Engagements (Routledge, London 2022), Arab Spring and Sectarian Faultlines in West Asia: Bahrain, Yemen and Syria (Pentagon Press, New Delhi, 2017) and the monograph India`s Relationship with the Gulf Cooperation Council: Need to Look beyond Business (MP-IDSA, New Delhi, 2014). He is also the editor of the book Geopolitical Shifts in West Asia: Trends and Implications (Pentagon Press, New Delhi, 2016). |

system/files/thumb_image/2015/india-approach-to-west-asia-book.jpg | ||||

| IDF’s Subterranean Challenge: Profiling Gaza Metro, Hamas’s Centre of Gravity | December 28, 2023 | Rajneesh Singh |

SummaryThe subterranean infrastructure developed by Hamas, popularly known as the ‘Gaza Metro’ consists of tunnels, command and control centres, living spaces, stores and contingency fighting positions. The infrastructure is the pivot of Hamas’s irregular warfare strategy and allows it to undertake both offensive and defensive operations and has been assessed as one of its centres of gravity. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) has been aware of the infrastructure but has possibly been surprised by the scale and sophistication achieved by Hamas in tunnel construction. The IDF’s technologies and doctrinal concepts are being tested every day in the ongoing war and will have a number of lessons for the Indian Army. Hamas has developed a complex subterranean infrastructure consisting of tunnels, command and control centres, living accommodation, stores and contingency fighting positions. The tunnels also have designated spaces for rocket-assembly lines, explosive stores, and warhead fabrication workshops.1 This infrastructure is famously known as the ‘Gaza Metro’. The Metro is reinforced by concrete and other building material and protected by blast doors, improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and booby traps. The tunnels have been in use since at least the early 1980s, and members of various Palestinian insurgent organisations have been known to use them since the first Intifada, beginning in 1987.2 In the aftermath of the 2021 Israel–Hamas conflict, Hamas leader, Yahya Sinwar claimed that Hamas has 500 kilometres of tunnel system and that the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) has damaged only 5 per cent of it.3 There is no way to verify Sinwar’s claim but is indicative of the magnitude of challenge the IDF faces in the ongoing war. Tunnel warfare is not new and dates to the ancient times. Jews used them against Romans in Judea in the first century.4 In the more recent times, the tunnels have been used in the battles of the Vimy Ridge, Messines and Somme of World War I, by the Viet Congs in Vietnam and in Mariupol, Bakhmut, and Soledar during the ongoing war in Ukraine.5 Gaza Metro is more than a just any military infrastructure. It is the centre of gravity (COG) of Hamas’s military wing.6 The Brief also attempts to analyse various aspects of operational significance of Gaza Metro using certain facets of the theoretical construct of COG advanced by Colonel John A. Warden of the US Air Force, Professor Joe Strange and Colonel Richard Iron, and Professor Antulio J. Echevarria II, retired US Army officer. History of Gaza MetroThe tunnels in Gaza predate Hamas. It is believed that they have been in use since the early 1980s7 after the city of Rafah was divided by the new border recognised in the 1979 peace treaty between Egypt and Israel.8 It was initially used by the divided families to communicate among themselves and by smugglers to transport goods. Hamas was raised in 1987 and soon it realised the military importance of the tunnels. It began digging tunnels in the mid-1990s, when Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was granted some degree of self-rule in Gaza by Israel. The group began tunnelling in earnest since 2005, when Israel withdrew from Gaza, and later when Hamas assumed power in 2006 election.9 As per the reports, the tunnels in 1990s were approximately one meter wide and smugglers used winch motors to haul goods along the sandy tunnel floors in hollowed-out petrol barrels.11 Hamas has since gained considerable expertise in tunnelling and construction of underground infrastructure which has advanced security features, sewage disposal and air-conditioning systems, etc. Hamas and Gaza MetroThe Gaza Strip has an approximate area of 365 square kilometres. If Yahya Sinwar’s claim of 2021 of Hamas having built 500 kilometres of tunnel system is true, then it would be equivalent of having 10 parallel north to south tunnel systems and eight parallel interconnecting tunnels running east to west.12 The Gaza Metro is so designed that there may be dozens of shafts leading to a tunnel at depths of between 20 and 80 meters. As per some accounts, the density of tunnels is so high that some crisscross at different depths.13 To create a subterranean system of this magnitude requires a dedicated organisation, high level of technological expertise, and resources in terms of trained manpower, equipment and money. Israeli officials have reported that Mohammad Sinwar, the brother of Yahya Sinwar, is heading the tunnel building project.14 Gaza has been under land, sea and air blockade by Israel and Egypt since 2007 and it was not expected to possess capability or resources to dig such an infrastructure. It was appreciated that Hamas has employed diggers using basic tools, used basic electrical fittings, and diverted concrete meant for civilian and humanitarian purposes towards tunnel building project. However, two of the tunnel systems discovered during the ongoing war, viz. near al Shifa Hospital and other close to the Erez crossing belies this assessment. The details of these tunnels have been discussed later in the Brief. Tunnel under al-Shifa HospitalIn the second week of November 2023, IDF’s 162nd Division was operating in Hamas’s “security quarter” of Gaza City, adjacent to al-Shifa Hospital. The troops of Givati Infantry Brigade reportedly found intelligence materials, weapons manufacturing plants, anti-tank missile launch positions and tunnels.16 On 17 November, the IDF located one of the shafts which led to the entrance of a bigger tunnel. This tunnel led to a blast door leading to a complex which had multiple rooms and one of them “was a spacious bedroom with two large beds and a large modern air conditioning unit, a kitchenette, a bathroom, and other facilities, as well as extensive plumbing and electrical wiring to enable all of the infrastructure”.17 The tunnel shaft leading to the main tunnel was approximately 2 metres high, lined with stones and concrete. The complex under the hospital was reportedly being used by Hamas as a command and control centre.18 Tunnel near Erez CrossingThe IDF reported on 17 December that it had discovered largest tunnel ever—four kilometre long and 50 metres deep—near the Erez crossing. The tunnel reinforced with concrete had electrical fitments and was wide enough to allow a vehicle to pass through. The IDF also released a video of Mohammad Sinwar driving a car through a tunnel. In another video released by the IDF, Hamas fighters were seen using a large drill. In the tunnel near the Erez crossing, the IDF reportedly found “unspecified digging machines” not reported earlier.19 One section of the tunnel was approximately 400 metres from the Israeli border. The IDF has informed that the Combat Engineering Corps’ elite Yahaom unit and Gaza Division’s Northern Brigade used “advanced intelligence and technological means” to uncover the tunnel network.20 Operational Employment of Subterranean InfrastructureThe infrastructure is the pivot of Hamas’s irregular warfare strategy and allows it to undertake both offensive and defensive operations. It offers Hamas asymmetric advantage, negating some of the technological advantages available to the IDF. The fact that Hamas has constructed the subterranean system under one of the world’s densest urban locations complicates the matter further for IDF. The system is designed to withstand IDF’s aerial and ground bombardment. The design and construction enable Hamas to locate its leadership, combat units, headquarters, command and control centres, weapons and supplies inside the complex. It also enables various military echelons to move freely between various prepared contingency positions. Hamas has located power generation and air-conditioning systems, plumbing and sewage disposal arrangements and food supplies within the infrastructure. This is helping its fighters to better withstand the siege laid by the IDF in the ongoing war. The tunnels also allow the fighters to escape the combat zone when they are decisively surrounded by the IDF, as was the case in battle near the al-Shifa Hospital. Hamas fighters are using tunnels to undertake offensive operations by infiltrating behind IDF positions and launching surprise attacks using snipers, rocket propelled grenades (RPGs) and other weapon systems. It enables small teams to appear undetected behind IDF lines, strike and withdraw. Gaza Metro as Centre of GravityClausewitz originated the concept of attacking the enemy’s centre of gravity which he described as “the hub of all power and movement, on which everything depends. That is the point against which all our energies should be directed.”21 A fighting force can have multiple centres of gravity and each centre will have an effect of some kind on the others. Hamas too has multiple centres22 and some analysts have described Gaza Metro as one of them.23 Warden’s Five-Ring ModelWarden has conceptualised “Five-Ring Model” related to COG, of which infrastructure is the third critical ring. The infrastructure relates to enemy's transportation system—that moves civil and military goods and services in the combat zone. Gaza Metro is essential to move troops, warlike stores, command instructions and intelligence around the battlefield and if the IDF can disrupt the movement, Hamas will have lesser ability to resist it. Although Warden agrees with Clausewitz’s description of COG as “the hub of all power and movement”, he goes further to describe it as “that point where the enemy is most vulnerable and the point where an attack will have the best chance of being decisive”.24 Warden’s first ring and the “most critical” ring is the command ring, which refers to the leadership and communication resources.25 It is assessed that Hamas’s leadership,26 including Yahya Sinwar, leader of the Hamas movement within the Gaza Strip, Mohammed Deif, commander-in-chief of the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades, and Marwan Issa, the deputy commander are hiding in the subterranean complex. Neutralisation of Hamas leadership is likely to have a decisive impact on the outcome of war. It is also expected that Hamas leadership would have constructed multiple safe hideouts inside the subterranean infrastructure, from where they can direct their subordinate commanders and units. It is also likely that only the most trusted Hamas members would be aware of these locations. It would require sustained intelligence operations by Israel to generate actionable intelligence. However, once the Hamas leadership is cordoned inside the tunnels, they would be extremely vulnerable to IDF operations. For the moment, the IDF is unaware of the exact location of the leadership and is destroying as much of this subterranean complex, as is possible to cause “strategic paralysis—by destroying one or more of the outer strategic rings or centers of gravity”27 —the infrastructure ring—the Gaza Metro. Strange and Iron’s TheoryThe Strange and Iron’s theory is helpful to identify the location of COG and the impact of operations against it. The theory aligns with the J.J. Graham’s translation of On War, published in 1874 which postulates that: “As a centre of gravity is always situated where the greatest mass of matter is collected, and as a shock against the centre of gravity of a body always produces the greatest effect, and further, as the most effective blow is struck with the centre of gravity of the power used, so it is also in war.”28 Hamas is cognizant of the incredible capability and resources of Mossad and Shin Bet to generate actionable intelligence and doctrinal, technological, and material superiority of the IDF to undertake combat operations. To counter Israel’s operational superiority, Hamas relies on low-tech solution in the form of subterranean infrastructure. The nature of infrastructure provides Hamas inherent physical protection, ease of movement and concealment to command and control elements and, combat, and logistic units. The Gaza Strip is one of the densest urban locations anywhere in the world. Tunnels in conjunction with urban infrastructure helps to create extremely potent defensive localities and killing grounds. The IDF hopes to find the leadership and fighters of the al-Qassam Brigades inside the Gaza Metro. Hamas has claimed that Gaza Metro is spread over 500 kilometres. Hamas is expected to dissipate its forces all along the Metro to avoid presenting a concentrated target to the IDF. However, once located, and fixed, the IDF will be able to neutralise Hamas forces with relative ease inside the tunnel system.

In the context of Gaza Metro, the subterranean nature of the infrastructure reinforced with concrete and other building material and further hardened using Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) and booby traps are the CCs. The camouflage and concealment arrangement to prevent detection of tunnels are the CRs while entry and exit points, ventilation and sewage arrangements, and communication infrastructure to enable command of Hamas fighters are the CVs. Echevarria’s TheoryEchevarria postulates COG is identified to achieve total collapse of the enemy—which is considered both as an effect and an objective.30 He further elaborates on the construct to suggest that the COG helps in identifying “way”—course of action—within an “ends-ways-means” construct to achieve annihilation of the enemy.31 This aspect may not be true when fighting an ideologically motivated and radical organisation like Hamas. It is possible that the IDF may identify and destroy Hamas’s tunnel system and thereby achieve destruction of Hamas’s military leadership and fighting units, however, in all probability the organisation will survive and grow, perhaps even more radical. “Terrorist groups are known to survive the loss of their leaders and members. It is quite likely that even if Israel destroys Hamas’s military wing, the idea of Hamas may survive.”32 IDF’s Tunnel Warfare CapabilityDevelopment of Technological CapabilitiesThe IDF has been aware of Hamas’s underground infrastructure and has been working towards new technologies and doctrinal concepts. When the first tunnel was discovered, the IDF established a laboratory, manned by engineers, physicists, geologists and intelligence operatives under the Gaza Division. The laboratory employed innovative soil research techniques, including scanning and decoding signals, and developed new detection techniques. In 2018, a review of then IDF’s underground combat capability was undertaken and a new training manual was published.33 The Israeli scientists and engineers have developed several new innovations, most of them are classified. The IDF’s specialised units have been equipped with special conical penetrators, drills, robotic systems that can inject special ‘emulsions’ either to seal or destroy the tunnels.34 IDF also makes innovative use of technologies such as ground and aerial sensors, ground penetrating radars, geophones, fibre optics, microphones, special drilling equipment and others. The Israeli scientists have developed radio and navigation equipment which can work underground, night vision devices that work in complete darkness and remote and wire-controlled robots that can see and map tunnels without risking the lives of the soldiers. The IDF has training simulators to train soldiers in near realistic situations. Israel has also developed variety of explosives and ground penetrating munitions, like the GBU-28 which can penetrate 20 feet of concrete or 100 feet of earth.35 Israel, over the years, has used satellite imageries, aerostat cameras and radars to map the tunnel system. These assets cannot reveal the layout of the tunnels but have been used to monitor location where cement-mixture trucks have halted over the years. The general area around these locations are possible entrances of the tunnels and may be probed using low-frequency, earth-penetrating radars, or basic probes.36 US and Israel have also been collaborating to develop newer technologies. Since 2016, Congress has appropriated US$ 320 million towards the project.37 IDF’s Special UnitsFighting enemy inside subterranean system requires specialised units. The Gazan tunnels were first discovered during the first Intifada and the IDF recognised the need to raise specialised units. It raised ‘Yahalom’, specialist commandos from Israel's Combat Engineering Corps. Yahalom specialises in discovering, clearing, and destroying tunnels and has the “Yael” Company to undertake engineering reconnaissance, “Sayfan” to neutralise the threat of non-conventional weapons (weapons of mass destruction). In addition, there are two explosive ordinance disposal units, and “Samur”, which specialises in tunnel warfare.38 The IDF has a specialised canine unit, “Oketz”, whose dogs are trained in special tasks such as attack, search and rescue, explosive detection, and weapon location.39 In addition, police and intelligence services too have specialist units—“like Sayeret Matkal, the Yamam, and others—who share best practices for dealing with terrorists and combatants underground.”40 IDF’s Subterranean OperationsThe IDF’s doctrine of subterranean warfare has evolved with the development of newer technologies to counter Hamas’s underground infrastructure, which too has become increasingly sophisticated and more potent with the passage of time. Hamas fighters have advantage in narrow, dark, collapsible tunnels with which they are familiar. The IDF protocol demands that soldiers do not enter the underground structures unless it has been cleared of Hamas presence.41 It uses many of the newly developed technologies including tracker robots and explosives to map and clear the tunnels. Namer Establishes CordonIsrael has one of the world’s best protected armoured vehicles, 70-ton Namer, to assist in tunnel demolition. It is armed with active defence system to intercept incoming rockets and missiles and machine guns to fight enemy on ground. The vehicle is equipped with cameras which allows the crew to operate in the safe environment from within the vehicle. The IDF employs Namer to provide protection by establishing a security cordon around the combat engineers who undertake the task of demolishing underground infrastructure.43 Having secured the area of operation, the IDF maps the structure either by using ‘exploding gel’ or other technologies. Thereafter, it has an option of either demolish the underground infrastructure using explosives or flood it with sea water. IDF uses ‘Exploding Gel’ to Map Underground InfrastructureThe ‘exploding gel’ is used to map the underground structure. Having located the entrance to the tunnels, the army engineers fill the passage with ‘exploding gel’ and fire it using detonators. The smoke travels the passage way and is used to map the underground infrastructure and also cause casualties to anyone inside the tunnels. The composition of the gel is classified and is brought in trucks because the scale in which it is used is huge. Several tons of gel are required every few hundred metres.44 IDF Deploys Pumps to Flood the TunnelsThe IDF maintains a tunnel flooding plan. In the middle of November 2023, it deployed five very large capacity pumps, approximately three kilometres north of Al-Shati refugee camp. Each of these pumps is reported to have capacity to draw thousands of cubic meters of water per hour from the Mediterranean Sea and flood the tunnels within weeks.45 On 12 December, The Wall Street Journal reported “Israel’s military has begun pumping seawater into Hamas’s vast complex of tunnels in Gaza.”46 It is still unclear how effective this tactic will be to achieve its intended objective of demolishing the underground infrastructure. The plan, however, has a downside since it is likely to contaminate Gaza’s fresh water supply.47 ConclusionHamas has expended a large percentage of its resources—money, material, and man-hours —to develop the subterranean infrastructure as a counter to technological and resource superiority of the IDF. It is the pivot around which Hamas’s defensive and offensive operations are planned and executed. The IDF, on the other hand, has been working to develop newer and more effective counters, however, there are yet to achieve the desired result. The ongoing Israel–Hamas war will bring out several new lessons of interest to Indian Army. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Defence Economics & Industry | Israel, Hamas, Warfare, Strategy | system/files/thumb_image/2015/gaza-metro-t.jpg | |

| The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Implications for Regional Security | December 22, 2023 | Jason Wahlang |

SummaryThe Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, dating back to the Soviet times, continues to impact regional geo-political, geo-economic and strategic trends. The interests of major regional and extra-regional powers remain crucial in shaping the conflict. Azerbaijan denied Armenia’s Prime Minister Nicol Pashinyan’s accusations about planning a military provocation in Nagorno-Karabakh on 7 September 2023. The Armenian leader’s statements came after reports of Azeri troop movement across the disputed borders. These verbal confrontations have further fuelled tensions between the warring neighbours, who have been embroiled in constant ceasefire violations. The events have derailed the ongoing efforts to find sustainable peace in the South Caucasus region. The conflict, dating back to the Soviet times, continues to shape regional geo-political, geo-economic and strategic trends. Historical BackgroundThe root cause of the conflict lies in the formation of the Transcaucasia Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) in 1921 under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin. This was followed by the Soviet People’s Commissar of Nationalities, Joseph Stalin, shifting control of Nagorno-Karabakh to the Azeri side of the Republic.1 This decision sowed the seeds for Armenia’s festering resentment, demonstrated in their continuous attempts to reverse the status quo. Unlike Azerbaijan’s Turkic population, a majority of ethnic Armenians continue to primarily reside in the Nagorno-Karabakh region. Notably, the dispute persisted even after the dissolution of the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and formation of the three separate Caucasus Republics in 1936. In 1988, when the Soviet Union was nearing dissolution, the Armenian population, backed by Armenia’s SSR in Nagorno-Karabakh, protested against the Azeri government and demanded independence.2 This resulted in all-out clashes between the two ethnic communities in the Nagorno-Karabakh region. The conflict escalated following the Soviet Union’s collapse amidst the two nations gaining independence. Nagorno-Karabakh emerged victorious in 1994, and the territory remained independent from Azeri control.3 Despite being victorious, the region was primarily dependent on Armenia until 2020. Map 1: Nagorno-Karabakh Territory Post the 1994 War

The Second Armenia–Azerbaijan WarThe frozen conflict over the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh reignited in 2020 marked by the second Armenia–Azerbaijan war. It ended up altering the status quo. The war led to Azeris establishing control over large swathes of Nagorno-Karabakh following the massive military support, mainly drones, from Türkiye, which, in fact, proved to the proverbial game changer.4 It was also during this time that Russia deployed its peacekeepers in the Lachin corridor to prevent re-escalation of the conflict as per the agreement on the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh ceasefire agreement. The significance of the Lachin corridor can be gained from the fact that it is not only a humanitarian corridor but also a lifeline connecting Armenia with the people of Nagorno-Karabakh for movement of resources. The ongoing blockade of the corridor by Azeri ‘eco-activists’ has reportedly created new humanitarian challenges for Nagorno-Karabakh amidst dwindling supplies and surging demand for essential commodities. Map 2: Nagorno-Karabakh Territory after Second Karabakh War

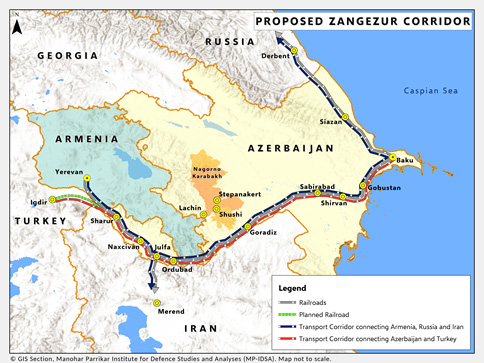

Yerevan’s PerspectiveRepublic of Artsakh (Armenian term for Nagorno-Karabakh) has been viewed as an extension of the Greater Armenian-Artsakh Connect5 , given its sizeable Armenian majority population (95 per cent population). Notably, Armenia has been viewed as Nagorno-Karabakh’s leading security provider by the territory6 and has a strong identity-based and historical connection with locals. The Ottomans, who ruled the Armenians until the First World War, have been accused by the latter of committing the Armenian genocide between 1915 and 1917.7 The Armenians believe that the Azeris, who are ethnic Turks, aim to emulate the Ottomans, perceiving the recent events as an extension of the genocide.8 Moreover, Armenians have accused the Azeris of reviving their inter-generational trauma of the Armenians by torturing Nagorno-Karabakh’s ethnic Armenians. 9 Another major factor that has fuelled Armenia’s current reaction to the conflict is its Prime Minister Nicol Pashinyan. Despite being re-elected in a snap election, his decisions have spurred protests by both locals and diaspora, who have called for his resignation. Recently, the Armenian Prime Minister recognised Azeri sovereignty over 86,000 kilometres of territory, including Nagorno-Karabakh.10 This worsened his approval rating, down to 14 per cent, among the population.11 Notably, his statements and perceived disregard for Nagorno-Karabakh’s significance for the larger Armenian society stems from a lack of connection to the conflict zone, unlike his predecessors. The first President, Levon Ter Petrosyan, was involved in the protests in the Soviet era and led Armenia against Azerbaijan during the First War. The other two leaders of Armenia, Robert Kocharyan and Sergh Sargasyan, were born in Stepanakert, Nagorno-Karabakh’s capital. Baku’s PerspectiveFor the Azeris, international recognition has been one of its trump cards when discussing the conflict. For example, the UNSC Resolution 884 on 12 November 1993 affirms Nagorno Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan.12 Azerbaijan has also frequently invoked the Soviet Union’s decision to transfer Nagorno-Karabakh to the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic. For the Azeris, the re-establishment of control over Nagorno-Karabakh was a promise waiting to be fulfilled by their incumbent leader, Ilhan Aliyev, since 2008.13 Meanwhile, efforts are underway to facilitate the return of the ‘displaced Azeri’ population, i.e., those forced out from Nagorno-Karabakh during the First War. Another corridor of significant importance to the leadership in Baku is the Zangezur (Syunik) Corridor. The idea of the corridor came into discussion only after the conflict in 2020. This proposed corridor would connect Azerbaijan with its exclave, Nakhichevan, through Syunik, a territory within Armenia. Additionally, it would ensure Türkiye’s direct land connection to Azerbaijan from Armenian territory. The corridor, if implemented, would provide a transportation route from Baku to Kars in Turkiye. Until now, Türkiye had only one border connected with the Azeri exclave Nakhichevan, which would be connected with Baku if the corridor was established. Map 3: Proposed Zangezur Corridor

Simultaneously, Azerbaijan has established a checkpoint near the Lachin Corridor. This has resulted in some Azeri eco-protestors14 blocking the corridor, affecting the local population of Nagorno-Karabakh. The corridor is critical for transporting goods and services for the local population, and therefore, any obstruction can deprive people of essential supplies. The Nagorno-Karabakh PerspectiveWith a predominantly ethnic Armenian leadership and social structure, locals see the conflict as integral to independence from Azerbaijan.15 The small Azeri presence, which existed before the collapse of the Soviet Union, has aspired to live under Azerbaijan’s control, now a possibility after the 2020 war.16 While the majority community has appreciated Armenia’s involvement in Nagorno-Karabakh, they have expressed disappointment with Nicol Pashinyan’s administration.17 The public has demanded a more proactive stance from Armenia, reminiscent of its past efforts.18 Since 2020, amidst the territorial changes, the locals’ main concern has been their future treatment by Azeri leadership, considering the ongoing hostility between the ethnic groups as well as between Armenia and Azerbaijan. These suspicions have heightened due to the Azeri blockade in the Lachin Corridor. The embargo has invited sharp criticism from Armenia as well as regional and major extra-regional powers. Notably, the United States, European Union, United Nations and France have been critical of the Azeri ‘eco-protestors’ actions.19 Genocide Watch, a prominent genocide-related organisation, has referred to the blockade as creating a genocide-like situation. It has placed the territory on Stage 9 (Extermination) and Stage 10 (Denial) of genocide.20 At the same time, Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh have frequently referred to Azeris committing cultural genocide through churches and Khatchkars’ (Armenian Crosses) destruction.21 These debates on genocide coincide with the Armenian understanding of the conflict’s current phase as an extension of the genocide carried out by the Ottomans. On the other hand, the Azeris have denied such claims and have rather blamed Armenia for provocation.22 Role of Major and Regional PowersRussia and Iran are considered Armenian allies whereas Türkiye and Israel back Azerbaijan. At the same time, the United States and the European Union (EU) appear to be seeking to expand their regional footprint. Russia remains one of the region’s key stakeholders concerning the conflict. Moscow has historically been connected to the conflict given their shared Soviet legacy. Russians have also been credited, mainly by Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, for trying to find a peaceful solution with their constant involvement in the various peace process. Russians brokered the 2020 peace deal, which involved placing Russian peacekeepers in the controversial Lachin corridor. Map 4: Lachin Corridor with Russian Peacekeepers

However, Russia has drawn criticism from the Armenian leadership for its perceived lacklustre efforts to find peace through the Collective Security Treaty Organisation.23 The Armenians expected a more proactive involvement similar to the one in Kazakhstan during the January 2022 protests. This is by virtue of Yerevan being a member of the CSTO with Russia having a military base in Gyumri. Armenia and Azerbaijan have been part of the European Union’s Eastern Partnership since 2009. However, Azerbaijan is considered closer to the EU than Armenia given the latter’s membership in Russia dominated Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) and CSTO. Notably, Europeans have traditionally supported Azeris due to Armenia’s robust partnership with Russia. Nevertheless, the somewhat strained relationship between Russia and Armenia amidst European efforts for peace is being increasingly viewed positively by Armenian leaders including inviting the peace missions.24 This indicates a potential Armenian shift towards Brussels in the long term. The EU has led peace missions and organised several meetings between government officials to establish regional peace. For example, the EU established two EU Missions; the first lasted for two months (October 2022–December 2022), and the second would be present in the Armenian territory till 2025, the same year the Russian peacekeepers would leave Lachin.25 However, the EU mission’s mandate is limited to Armenia due to Azerbaijan’s refusal to allow them into Azeri territory.26 This has, however, not affected the relationship between the EU and Azerbaijan. The United States’ involvement in this region could be linked to exploiting any vacuum created by Russia due to its involvement in Ukraine. The regional geopolitical turmoil could see the US attempt a more hands-on approach. The US has sought to play the role of a peace negotiator and moderator between the two governments while also being a member of the OSCE Minsk peacekeeping initiative. The latest involvement of the United States in the region is the 10-day routine military exercises it conducts with Armenia in Yerevan.27 Türkiye has a strong relationship with its Turkic brethren in Azerbaijan and sees it as a gateway to the region.28 Its ties with Armenia are almost non-existent, mainly due to the historical animosity that exists due to Türkiye’s predecessor—the Ottoman Empire. Since Türkiye sees Azerbaijan as its primary contact point, it has developed a strong relationship with it. Türkiye’s diplomatic and military support, particularly its famed Bakhtiyar drones, proved decisive for Azerbaijan in the second war.29 Iran remains a close partner of Armenia despite recognising Nagorno-Karabakh as Azeri territory as per international norms. Iran’s closeness to Armenia is also co-related to its regional hostility with Israel, which provides Azerbaijan with 70 per cent of its total military supplies.30 This threat has existed since the 1990s with the first post-soviet Azerbaijan President, Abulfaz Elchibey, threatening to march to Tabriz (Azeri-populated Iranian territory),32 to the current establishment of Ilhan Aliyev declaring the need to secure minority Azeris in Iran. He referred to them as his ethnic kin.33 Mahmudali Chehreganli, the self-proclaimed and exiled leader of South Azerbaijan (North West Iranian territory) National Awakening Movement, in an interview with state-run AZ TV, called for the overthrow of the Iranian leadership, terming it as hateful.34 Such threats have risen after the 2020 conflict, particularly after Azeri successes on the battlefield.35 Meanwhile, Iran’s dispute with Azerbaijan is also regarding the establishment of Zangezur corridor, which would connect Baku with its enclave Nakhichevan, the closest border that Iran shares with Azerbaijan.36 Türkiye supports the corridor’s idea, whereas Iran and Armenia have been opposed to it.37 Iran fears that the corridor could block Iranian land connection to Armenia if it exists.38 This would also obstruct its connection with Georgia which bypasses Azerbaijan and Türkiye. It has led Iran to be vocal against any territorial changes within Armenia which could happen due to the corridor. ConclusionThe frozen conflict, reignited in 2020, remains the key hurdle to sustainable peace in the Caucasus. It continues to undermine regional security. Amidst continued ceasefire violations and lack of peace treaty, the solution to the conflict appears to be a distant dream. Meanwhile, the interests of regional and extra-regional powers remain crucial in shaping the conflict. Russia’s war in Ukraine may see Moscow cede ground to others in what has been Russia’s traditional sphere of influence. Recently, Armenia recalled its envoy to CSTO amidst murmurs of discontent with the military organisation remaining neutral in Armenia’s moment of national crisis. As such, the US and the EU in particular could seek to expand their footprints in the region amidst the overhang of Russia–West confrontation. Notably, older peace formats, including the OSCE format for peace, which was instrumental in negotiating a peace deal during the 1990s, appear to have lost relevance. Instead, peace deals proposed by Iran and Türkiye have gained traction, thereby highlighting their growing regional influence in the Caucasus. However, given the strained relations of these countries with the warring nations, i.e., Iran with Azerbaijan and Armenia with Türkiye, the chances of concluding a credible peace treaty appear slim. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Europe and Eurasia | Azerbaijan, Armenia | system/files/thumb_image/2015/armenia-azerbaijan-t_0.jpg | |

| Assessing Japan’s Diplomacy in 2023 | December 21, 2023 | Arnab Dasgupta |

Japan has had a busy diplomatic year. It had to adapt its foreign policy on account of the structural challenge posed by China and was also called upon to display dexterity as a gamut of old and new territorial and ideological conflicts reignited in West Asia and Eastern Europe. Japan’s neighbourhood underwent milestone shifts that required deft tending by Tokyo. The infusion of defence-oriented language into its rhetoric had to take into account reactions across all of Asia and the world. Further, due to an internal political reshuffle, Japan has had two foreign ministers, giving rise to the unusual phenomenon (in Japan) of a prime minister explicitly staking a claim to make a personal impact on foreign policy. Given these trends, Japan’s diplomacy in 2023 marks a significant inflection point. Rapprochement with the Global SouthThe first key trend noticeable in Japan’s foreign policy in 2023 has been its ardent embrace of the Global South concept. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida chose the occasion of his visit to New Delhi in March to announce his new plan for a Free and Open Indo-Pacific.1 This plan gave importance to South and South-East Asia as well as Africa as key regions for Japan’s strategic engagement. Kishida’s invitation to India and Indonesia, two leading Global South nations, to the G-7 summit in Hiroshima, as well as his interactions with Global South leaders during the G-20 summit in New Delhi,2 spoke about Japan’s sincerity in putting its rhetoric into practice. Kishida was ably assisted in this enterprise by Foreign Ministers Yoshimasa Hayashi and (post-September) Yoko Kamikawa. Both Hayashi and Kamikawa used their visits to Global South countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America to reinforce Japan’s commitment to convey their concerns to the industrialised Global North. Even the Imperial family was roped into the role of de facto ambassadors of Japan’s message. Emperor Naruhito and Empress Masako visited Indonesia in June, Crown Prince Fumihito (the Emperor’s brother) and Crown Princess Kiko visited Vietnam in September, while Princess Kako’s (daughter of the Crown Prince) successful visit to Peru in November compensated for the lack of visits by Kishida to the region. Neighbourhood DiplomacyDevelopments in the neighbourhood added new dimensions to Japan’s diplomatic calendar. The inauguration of a new President of the Republic of Korea, Yoon Suk-Yeol, in December 2022 augured a sea-change in that country’s blind-spot towards Japan. Yoon surprised many among his own countrymen by seeking out an engagement with Kishida in March. The engagement followed a long freeze in bilateral ties after the previous South Korean administration of Moon Jae-in allowed a Supreme Court judgement on Japan’s historical atrocities in the peninsula to affect bilateral security and political cooperation in 2018. Since that first meeting in March, Yoon and Kishida met each other seven times over the next nine months,3 a frequency rare in the annals of diplomacy. During Kishida’s visit to Seoul in May, Yoon went further than any other South Korean leader in de-emphasising issues of history, wholeheartedly echoed by Kishida. The rapid improvement in ties resulted in some tangible benefits. The ROK did not oppose Japan’s release of seawater used in the clean-up of the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor in August. Yoon and Kishida, in association with President Joseph Biden, agreed to resume joint military and security cooperation against the actions of North Korea and China.4 China itself proved to be the elephant in the room in 2023, particularly in the latter half of the year as Japan embarked on the wastewater discharge from the Fukushima Daiichi plant. It not only insisted on opposing the United Nations specialised agencies’ stance on the safety of the discharged water, but also embarked on an unprecedented campaign against Japanese citizens, mobilising crowds to vandalise the Japanese Embassy and a Japanese school, pre-emptively banning seafood and other exports from Japan, and encouraging a unique prank-call campaign against Japanese domestic entities.5 Japan also showed willingness to escalate matters by joining with the US and the Netherlands to restrict Chinese access to advanced semiconductor manufacturing technology in October.6 Japan widened its sanctions list in December to include Chinese government labs engaged in nuclear research as a protest against the latter’s expansion of its nuclear arsenal.7 Nevertheless, the two sides did resume informal military talks,8 and Kishida met President Xi Jinping on the side lines of the APEC Summit in November to discuss bilateral issues.9 Emphasising Defence TiesAnother discernible trend in Japan’s diplomacy in 2023 was the uptick in mentions of defence and security issues in its engagements with relevant countries. Kishida’s visit to New Delhi in March saw him engaging Prime Minister Narendra Modi on issues of defence technology cooperation. Kishida’s public commitment later in the summer to reconsider Japan’s strict curbs on export of lethal defence technology in the teeth of opposition from pacifist quarters of the Japanese political sphere saw him using his visit to Ukraine as an opportunity to shake up established norms. His subsequent visits to North Africa and South-East Asia, as well as those of his deputies to Europe, the US and West Asia have shown a consistent throughline under which Japan has committed to work cooperatively with partners and like-minded countries to ensure not only maritime security, but, as part of its comprehensive national power, economic, energy and technology security as well. One of the most distinctive advances under this overarching theme has been the introduction of the Official Security Assistance (OSA) program10 as a complement to its Official Development Assistance. With an initial budget of 450 million Japanese yen, the OSA is intended to provide non-lethal security assistance to key countries. The first recipients, Fiji, Malaysia, the Philippines and Bangladesh, are indicative of Japan’s areas of interest, and Tokyo has shown its openness to considering an expansion of the program to a global scale in partnership with other net security providers in their respective regions. The fact that the Philippines is presently embroiled in a stand-off against China in the Second Thomas Shoal indicates Japan’s strategic choice in ensuring smaller countries are capable of pushing back against Chinese maritime aggression. Enhancement of the Prime Minister’s RoleThe year 2023 also marked the year when Japan’s diplomacy underwent an institutional reworking in terms of who ‘does’ foreign policy. In essence, this change turned the Japanese prime minister into the key effector of policies, with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs being placed in a secretarial role. Evidence of this could best be found in the announcement of the replacement of Yoshimasa Hayashi as the nation’s chief diplomat while Hayashi was on a trip to Ukraine, and the rapid substitution of Yoko Kamikawa—with no significant prior experience of foreign affairs, to the position. Kishida’s desire to take a greater role in foreign affairs came from a press conference he delivered in the wake of the reshuffle of his cabinet in September. He noted that while “[m]inisters have an important role to play…summit diplomacy is a big component as well. I myself intend to play a major role in such summit diplomacy.”11 As observers of Japan’s political arena know well, Japanese prime ministers tend not to be primarily aggressive salesmen of their country abroad, choosing to focus instead on leaving behind domestic legacies. Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda is the epitomical example. A former bureaucrat, he was central to the engineering of the ambitious industrial policies that caused what we now know as Japan’s high-speed economic growth era, from 1960 to 1973. Some prime ministers, to be sure, have been outward-looking in terms of their legacy-building: Shigeru Yoshida, father of the Yoshida Doctrine espousing close security ties with US in lieu of a focus on economic growth at home, and Shinzo Abe, come to mind. However, none so far have staked quite such an overt claim to diplomatic primacy as Kishida. It is widely speculated, to some extent justly, that Kishida’s low domestic support ratings, due largely to internal policy failures such as the talk of new taxes to increase defence spending and the failure to completely repudiate the Liberal Democratic Party’s cosy ties with the controversial Unification Church, may have led him to seek diplomatic successes. However, this remains a double-edged sword. Should his key initiatives, such as the OSA or outreach to the Global South, sour, he will be doubly blamed for frittering away valuable policy space to pursue arcane objectives abroad. As such, Kishida’s ensuing moves in this sphere bear observation. ConclusionIt is interesting to note that Japan, despite its long-standing image as a staid, reactive power, stands at a diplomatic crossroads of increasing significance at the end of 2023. Which road it takes in 2024 is not easy to predict, but there are certain significant mileposts which could signal the direction. One crucial milepost will be how Japan manages its ties with the Global South, especially with India. Another crucial marker will be the success (or failure) of its new policy of studied neutrality in West Asia, which will indicate whether it is prepared to deviate from the Western world’s script should its interests be seriously affected. Third, and finally, it would be interesting to see whether Prime Minister Kishida continues to expand his role in diplomacy, and to what extent he can claim the space to do so before encountering significant bureaucratic pushback. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

East Asia | Japan | system/files/thumb_image/2015/japan-t_0.jpg | |

| India–Nigeria Defence Cooperation: Contexts, Drivers and Prospects | July-September 2023 | Eghosa E. Osaghae |

Nigeria and India have a long history of cordial and robust bilateral relations and defence cooperation. This article examines the nature, contexts, drivers, content and future of defence cooperation between the two countries in terms of continuity and change. It analyses how global and African currents including rivalry amongst world powers and the new scramble for Africa, as well as transformations and changes in the conceptions and challenges of security, have shaped defence relations between them. From the ‘traditional’ and more historically continuous domains of peacekeeping, military training and capacity-building, the scope of cooperation has expanded to include non-kinetic approaches to defence, counterterrorism, counterinsurgency, cybersecurity, research and development, medical security, and maritime security in the oceans and blue economy. The article shows that defence cooperation has been revitalised and enlarged since Nigeria’s return to civil democracy in 1999, and concludes that although Nigeria and India are unequal partners and Nigeria is more dependent on India’s benevolent power, military goods and services, defence cooperation has been mutually beneficial to both countries. |

||||

| India–Africa Military-cum-Defence Diplomacy: A Viable Option | July-September 2023 | Swaim Prakash Singh |

The relationship between India and Africa is based on historical ties forged during colonialism and apartheid. However, due to a wave of liberalisation and privatisation in the 1990s, India’s involvement in Africa shifted significantly. Despite active engagement for more than 70 years, India’s long-term strategy for expanding its relations with Africa lacked clarity and wherewithal. As a result, India has also been unable to capitalise on its enormous historical goodwill in the region. However, it may change as ideological and political issues are taking a backseat. Also, rising economic and security ties have recently given the partnership a fresh start. However, given the unprecedented opportunity to engage with African countries to address their security concerns and thus strengthen relations, it is observed that initiatives to this end are insufficient. What else can be done to make the engagements more meaningful and worthwhile? Can the defence diplomacy factor be one of the strategies for strengthening bilateral security cooperation? Can the bilateral engagement move to other military arenas beyond UN Peacekeeping Operations? Can the Indian military contribute more to the African countries’ capacity-building? Can India think of establishing a military base beyond the maritime domain? Can India capitalise on Africa in its effort of ‘Atmanirbharta’ to ‘Bharatnirbharta’? This article attempts to answer these questions by focusing on the need for India and Africa to strengthen their relationships at all levels, particularly in defence and military diplomacy. |

||||

| India–Africa Defence Cooperation | July-September 2023 | G.G. Dwivedi |

India and Africa are bonded by centuries old historic ties, which are deeprooted, diverse and harmonious. As geographic neighbours, the two are linked by the Indian Ocean. Given the shared past, diaspora connection and future aspirations, India and Africa are natural partners. With the formation of India–Africa Forum Summit (IAFS) in 2008, bilateral cooperation gained huge traction and mechanism became more structured. India has accorded top priority to Africa in its foreign policy and strategic calculus. Consequently, 18 new embassies/ high commissions have been added over the last five years, taking the numbers to 47. Even bilateral trade has shown a sharp increase, of US$ 98 billion in 2022–23. During the COVID-19 pandemic, India took a number of steps to help Africa by expediting the delivery of essential medicines and vaccines. |