You are here

Quad-at-Sea Observer Mission: Exploring the Prospects of Coast Guard Collaboration

Summary

The Quad-at-Sea Observer Mission is scheduled to commence from 2025. Coast guard vessels are better suited for constabulary operations than naval vessels, which are principally designed for fighting wars.

On 21 September 2024, the fourth in-person Quad Leaders’ Summit was held in Wilmington, Delaware. The Quad nations unveiled various initiatives in the areas of health security, Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR), maritime security, infrastructure development, Critical and Emerging Technologies (CETs), clean energy, cybersecurity and people-to-people exchanges.1 The most notable among these initiatives is the announcement of the Quad-at-Sea Observer Mission in 2025. This initiative will involve the joint deployment of coast guard assets of the four nations in the Indo-Pacific maritime region.

The initiative has been envisaged for strengthening the maritime policing capabilities of the Quad nations, taking into context the aggressive use of coast guard and maritime militia vessels by China for asserting territorial claims in the South China Sea (SCS) and East China Sea (ECS). In the joint statement, the Quad nations have condemned this trend without explicitly mentioning China.2 The joint deployment of coast guards for enhancing maritime policing in the Indo-Pacific region has been under discussion among several nations for nearly a decade.3 It is likely that the Quad-at-Sea Ship Observer Mission may serve as a precursor to greater collaboration among the coast guards of the region.

Scope of Coast Guard Operations on the High Seas

A nation’s maritime security outlook is largely shaped by three key factors. First, protecting the nation’s sovereignty and interests from the threats emanating from the seas. Second, projecting national power in distant seas for deterring adversaries and for strengthening diplomatic relations with friendly countries. Third, ensuring ‘Good Order at Sea’ for safeguarding its economic interests by facilitating uninterrupted maritime trade and exploitation of marine resources. The maritime security apparatus of most nations normally constitutes its navy at the helm, supplemented by coast guard and other coastal policing agencies. The scope of operations of the navies and coast guards are doctrinally enunciated across three distinct roles which has been shown in Figure. 1.

In an effective maritime security strategy, the scope of operations of a nation’s navy and coast guard should not be exclusively restricted to either one or more of the above illustrated roles. Rather, the synchronised operations of both the navy and coast guard across the three roles is essential for ensuring maritime security both in times of war and peace. However, the intrinsic military character of navies makes them more suited for serving the military and diplomatic role.4 The grey-hulled ‘warships’ which are the principal assets of the navies essentially serve as instruments of a nation’s military power. Naval assets are primarily armed and equipped for the purpose of engaging in combat during times of war. During peacetime, naval warships are utilised as instruments of diplomacy for strengthening relations with other nations through joint exercises and port visits.

The constabulary role by nature is different from the military and diplomatic role. In the constabulary role, maritime assets are employed for enforcing national laws and implementing regimes established by an international mandate.5 Hence, the policing of a nation’s territorial seas and its contiguous maritime zones for deterring and preventing illicit activities is the core objective of constabulary operations. Establishing a continuous maritime presence and authority to enforce law on the sea are the key requirements for constabulary operations as opposed to application of force. In order to enforce national and international laws on the seas, it is essential for maritime policing force to have the wide powers to arrest both foreigners and national citizens. This is a power that a naval warship cannot exercise due to the globally accepted legal norms that constrain the use of the military in civilian law enforcement.6

At the same time, although coast guard agencies have the powers to make arrests at sea, its legal remit is limited to the jurisdiction of the coastal states. In the territorial sea and contiguous zones, the coast guards have the power to arrest by the virtue of domestic law of the respective coastal states that govern these areas. In the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), the coast guard derives law enforcement powers from Article 73 of the UNCLOS which lays down the coastal state’s right to act against economic violations perpetrated by foreign or unlawful vessels.7 But in high seas, the coast guard does not have law enforcement powers. However, the coast guards can be empowered for law enforcement on the high seas through inter-governmental, regional or international agreements. Such a measure can allow coast guard to be deployed on the high seas for constabulary operations.

Deploying naval warships equipped with sophisticated weaponry for constabulary operations can be an expensive proposition considering the wear and tear these assets incur during extended periods of deployment.8 On the other hand, deploying lightly armed and simplistically designed coast guard vessels are more cost-effective as they are operationally efficient platforms for extended deployment. In this context, the white-hulled ‘lawships’ of the coast guard are better operationally suited for constabulary operations than the grey-hulled ‘warships’ of the Navy.9

However, in many nations including India, the navy continues to remain an integral element of their coastal security strategy. After the terrorist attacks on Mumbai on 26 November 2008, there was a need for an efficient and effective constabulary mechanism for facilitating seamless coordination between the various maritime law enforcement agencies. Hence in India, the responsibility for overall coastal security has been mandated to the Indian Navy in close coordination with the Indian Coast Guard (ICG), State Marine police and port authorities.10

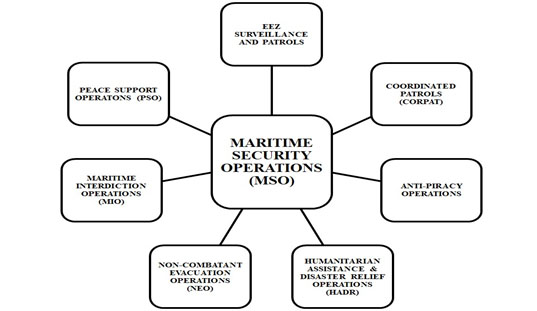

Geoffrey Till in his seminal work Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century highlights how the Navy’s functions in constabulary role essentially resembles the operations of coast guards.11 He also brings out, how the term Maritime Security Operations (MSO) is increasingly being used to encapsulate the wide range of operations that constitute the constabulary role of navies and coast guards. Figure 2 shows the various types of MSOs as identified by the Indian Navy.12

Source: “Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy”, Indian Navy, October 2015.

There is a common perception that the scope of coast guard operations is restricted to the maritime policing of a nation’s territorial waters and EEZs. However, the global maritime environment has undergone a profound transformation over the last few decades. This transformation has been characterised by the increasing dependence of the global economy on the extensive maritime trade networks since the advent of globalisation. These networks are increasingly becoming vulnerable to disruptions by various kinds by maritime threats. First, this includes illicit maritime activities like drug trafficking, arms smuggling, piracy and Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing. Second, international armed conflicts continue to pose major threats to maritime trade networks. This is evident from the ongoing Ukraine War and West Asian crisis which have led to major disruptions in the Black Sea and the Red Sea respectively. Finally, contestations over overlapping maritime claims in the regions like SCS and ECS can also potentially create serious disruptions.

Due to these factors, the emphasis on maintenance of good order at sea has become much more pronounced across the maritime security strategies of nations. Geoffrey Till observes that major maritime powers have begun to recognise the global indivisibility of good order at sea.13 As a result, nations have begun to extend their homeland defences forward onto the high seas in order to intercept problems before they arrive into their coasts.14 This rationale has extended the scope of coast guard operations beyond the territorial waters and EEZs to the high seas. For example, after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the US government immediately established a 96-hour prenotification system for all US-bound ships. The US Coast Guard (USCG) was tasked to enforce this system through the establishment of the National Vessel Movement Centre. This was done to enable the USCG to acquire prior information on crew, passenger and cargo manifests for identifying suspicious vessels while they are at high seas.15

Such an approach has also been adopted by Australia in its efforts to combat seaborne illegal immigration into its territory. In 2013, the then Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott established Operation Sovereign Borders policy. As part of this policy, Australia has employed its coast guard known as Maritime Border Command (MBC) for detecting and stopping vessels laden with illegal immigrants and asylum seekers on the high seas.16 This policy has also created a bilateral issue with Australia’s maritime neighbour, Indonesia, from where most of these vessels originate. Indonesia on several occasions protested against this policy citing the intrusion of Australia’s MBC vessels into its jurisdictional waters.17

Hence, it must be noted that policing the vast expanse of high sea is not possible without the coordinated efforts and pooling of resources of the key stakeholders of a maritime region. Due to this, over the last decade, many international and regional forums have emerged for facilitating dialogue and cooperation among the coast guards in the world. Some of these forums are the Coast Guard Global Summit (CGGS), European Coast Guard Functions Forum (ECGFF), Heads of Asian Coast Guard Agencies Meeting (HACGAM) and ASEAN Coast Guard Forum (AFC). At a bilateral level, the ICG has signed several Memorandum of Understanding (MoUs) with Coast Guard and maritime policing agencies of several countries.18 In line with these developments, the Quad-at-Sea Observer Mission can be seen as the grouping’s effort to strengthen maritime policing in the Indo-Pacific region.

Constabulary Challenges in the Indo-Pacific

Maintaining ‘Good Order at Sea’ in the Indo-Pacific region is both vital and challenging given the distinctive maritime orientation of its trade connectivity.19 Geographically, the Indo-Pacific is a vast maritime region stretching from the Western Pacific in the east to the Western Indian Ocean in the west. The trade shipping passing through this region accounts for nearly 42 per cent of exports and 64 per cent of imports of the total global volume.20 The key sections of this extensive maritime trade network is through the enclosed and semi-enclosed seas connected to open seas via chokepoints like the Strait of Hormuz and the Malacca Strait. These arterial routes are highly susceptible to disruptions by armed conflicts, piracy and other contingencies, as evident by the ongoing Red Sea crisis and resurgence of piracy in the Gulf of Aden.

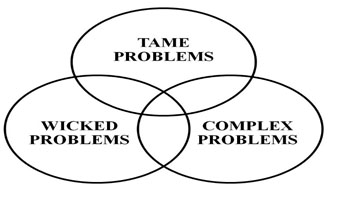

As disruptions to these routes can be highly detrimental to the global economy, ensuring good order at sea is extremely important. Securing these arterial routes through the vast expanse of the oceans is beyond the capacity of any single nation and requires a collective effort. However, this can be challenging considering the geopolitical complexities of the region characterised by political instabilities, governance deficits and conflict-prone national polities.21 This is accompanied by a high degree of pre-existing international tensions, rivalries and disputes arising over contested maritime claims and differing interpretations of international laws.22 Sam Bateman has classified these multifaceted challenges into three distinct categories which are shown in Figure 3.23

Source: Sam Bateman, “Solving the Wicked Problems of Maritime Security: Are Regional Forums up to the Task?”, Contemporary Southeast Asia, Vol. 33, No. 1, April 2011.

As per Bateman, ‘Tame Problems’ are challenges for which there is common ground among the stakeholders of the Indo-Pacific region in clearly defining the nature of a problem and envisaging a solution to address it. Challenges such as piracy, terrorism and HADR issues along with other maritime crimes like trafficking of drugs, arms and humans are classified as Tame Problems.24 The common consensus in addressing these issues has been reflected in several regional forums like ASEAN, ARF, ADMM/ADMM-Plus, IORA and East African Community (EAC).

In contrast to this, ‘Wicked Problems’ refers to perplexing issues that arise from the fundamental differences between stakeholders in their perspectives to certain problems. As a result, formulating an effective solution for these problems has become an issue.25 This is because these problems primarily arise from the stakeholders’ deeply held convictions about the correctness of their own positions.26 Such wicked problems have essentially manifested across the Indo-Pacific in the form of contested maritime claims. A nation’s own perception of its territorial integrity and varying interpretations of the laws of the sea are main causes of such contestations. Sporadic naval build-ups and localised confrontations in the Indo-Pacific region are due to such wicked problems that eventually undermine good order at sea.

The third category ‘Complex Problems’ are issues on which there is global consensus that they pose credible maritime security threats, but some nations have reservations and are uncomfortable about addressing them. Such problems are associated with issues like environmental concerns and IUU fishing.27 Although these issues are bound to create detrimental long-term implications in the Indo-Pacific, there is lack of consensus among the key stakeholders in acknowledging them as maritime security issues. Bateman opines that these differing perceptions are influenced by geographic circumstances and maritime interests of individual countries.28

For example, Indonesia which is a large archipelagic nation has one of the largest EEZs in the Indo-Pacific. Due to this it also happens to be one of the biggest victims of IUU fishing in the region. Its expansive EEZ has become a hotbed for foreign trawlers, most of them from its neighbouring countries such as Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam and Papua New Guinea.29 As a result, IUU fishing is amongst major maritime security issues in Indonesia’s national discourse. But some nations in the region like Thailand, South Korea and Singapore are less concerned about IUU fishing as a key maritime security issue. This is because these nations have very small area of maritime jurisdiction and rely on Distant Water Fishing (DWF) fleets to meet their domestic demands.30

Assessing the Key Prospects of Quad-at-Sea Observer Mission

In the face of the three-dimensional constabulary challenges that prevail in the Indo-Pacific Region, the Quad-at-Sea Ship Observer Mission has significant operational scope in addressing each of them in varying capacities. The initiative has the potential to serve as an effective mechanism that can translate the existing regional consensus into collective action for tackling the various tame problems of the Indo-Pacific. On the other hand, it also has the potential of creating a working consensus among the key stakeholders on complex problems like IUU fishing. Finally, such an initiative can constructively contribute to managing and mitigating escalations that arise out of the wicked problems in contested maritime zones within the Indo-Pacific. Some of these key prospects of this initiative can be envisaged under the following heads.

Identification of High-Risk Areas (HRA)

The policing of the vast stretches of the high seas is not possible without the identification of High-Risk Areas (HRA) or precautionary zones. The areas where there is a high level of risk to the safety of commercial vessels and their crew are designated as HRAs. This may be due to the prevalence of armed conflicts, military tensions, piracy and other illegal maritime activities in certain regions.31 Traditionally, such HRAs may be identified near coastal waters in narrow seas and chokepoints where threats to shipping may emerge. The limited geographic expanse of these maritime regions can enable stakeholders to accurately identify the HRAs and deploy adequate resources to secure shipping transiting through these regions. However, this can be far more challenging on the high seas considering their vast geographic expanse. The joint deployment of coast guard assets can help the Quad nations to map the high seas for identifying HRAs with the Indo-Pacific region. This would enable the Quad coast guards to efficiently patrol and monitor these HRAs through appropriate asset allocation, dedicated support infrastructure and a viable rotational plan.

Establishing Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)

Maritime law enforcement is a multi-step process involving three district phases. The first phase involves detecting illegal activities and tracking of suspicious vessels. The second phase involves interception, interdiction and boarding of these vessels. The third phase involves carrying out searches, inspection, seizure of illegal consignments and arrest of criminals from these vessels. The process of maritime law enforcement in the coastal waters and EEZs is guided by the operational procedures of the respective coast guards and policing agencies. However, maritime law enforcement on the high seas can be complicated given that the operational procedures of different navies and coast guards may vary.32 In this context, the Quad-at-Sea Ship Observer mission can play a crucial role in establishing certain common SOPs for Quad coast guards. Such SOPs can also be adopted by other regional coast guards, leading to a more streamlined maritime law enforcement mechanism across the Indo-Pacific.

Enhancing Interoperability through Pooling of Assets and Resources

Improving interoperability among the Quad coast guards has been highlighted as a key objective in the Wilmington Declaration. 33 This is due to the fact that policing the high seas requires the optimal utilisation of limited assets and resources available with the coast guards. Hence, pooling of these assets and resources becomes instrumental for effectively patrolling and responding to other contingencies on the high seas. The Quad’s initiative could pave the way for the establishment of agreements and mechanisms amongst the four nations for pooling their coast guard assets like vessels and aircraft. This can facilitate greater information sharing and exchange of best practices through capacity-building programmes.

Creating and Safeguarding Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

At sea, the Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are designated zones where human activities are restricted or in cases even prohibited by nations or international regimes. Such MPAs are created to safegaurd the marine ecosystem that is increasingly being threatened by predatory human activities at sea like IUU fishing. These MPAs are critical for the replenishment of fish stock, protection of endangered species and controlling pollution. The establishment of such MPAs in waters under national jurisdiction such as territorial seas and EEZs is relatively easy as it is subjected to a nation’s own discretion. On the other hand, the establishment of such MPAs on the high seas is far more complex as they are beyond the national jurisdiction of any particular nation. Due to this, only a few MPAs exist on the high seas thus far as it requires the consensus among several nations.

Over the last decades, the need for the establishment of such MPAs beyond national jurisdiction has been acknowledged by the international community. The EU’s OSPAR convention is an important example of such an effort. This convention is a high seas treaty of 15 European nations who have collectively established a network of MPAs with a total surface area of 14,86,053 square kilometers across the North East Atlantic Region. The recent adoption of the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement by the UN on 19 June 2024 is another international high sea treaty focusing on the creation of MPAs. Prime Minister Narendra Modi led Union Cabinet on 8 July 2024 approved India’s accession to this treaty.34 According to the Indian government, the BBNJ Agreement allows India to enhance its strategic presence in areas beyond its national jurisdiction and demonstrate its commitment towards protection of the marine ecosystem.35 The establishment of MPAs on the high seas of the Indo-Pacific is highly crucial as IUU fishing is a pressing maritime security issue of the region.

But the establishment of MPAs on the high seas alone is not sufficient to effectively combat IUU fishing. According to a report published by the Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association (WIOMSA), the establishment of MPAs ironically leads to the illegal fishers to deliberately indulge in exploitative fishing in these zones.36 This is because these fishers are aware that there is greater abundance of fish in MPAs.37 The weak MPA management regimes lacking the capacity and resources to efficiently enforce restriction on human activities in these designated zones is another critical challenge in combating IUU fishing. Hence, it is important that these MPAs on the high seas are adequately protected by the stakeholders of a maritime region. This is where Quad’s joint deployment of their coast guard assets can play a vital role in combating IUU fishing in the Indo-Pacific. Such a collaboration would enable the Quad nations to identify the zones on the high seas that can be designated as MPAs. Once identified, the Quad can deploy their coast guard assets to protect these MPAs from illegal fishers by enforcing an effective Monitoring, Control and Surveillance (MCS) cover over these zones.

Mitigating Escalation in Contested Maritime Regions

As brought out earlier, addressing maritime security challenges in certain regions within the Indo-Pacific can be extremely challenging given the overlapping jurisdiction and contested maritime claims. The extended deployment of naval vessels in these regions for constabulary operations can provoke tensions among the claimant states. The presence of naval vessels in such sensitive areas can potentially lead to escalation and militarisation instead of addressing the maritime security issues. As a result, Bateman points out that in such areas, the coast guard vessels are better suited for constabulary operations than naval vessels. He argues that the arrest of a foreign vessel by a naval vessel may be highly provocative and can lead to diplomatic standoff between the claimant states.38 On the other hand, the arrest made by coast guard vessels may be considered as legitimate law enforcement and signal that the arresting party perceives the incident as relatively minor.39 In this context, through the deployment of their coast guard assets, the Quad has the opportunity to address the maritime security challenges even in contentious regions like the SCS and ECS.

Conclusion

Addressing maritime security issues and upholding Freedom of Navigation (FON) in the Indo-Pacific has always been the core agenda of the Quad. Hence, in the Quad maritime security agenda, naval cooperation between the four nations will always remain relevant. But through coast guard collaboration, the Quad has the opportunity to address some of the complex maritime security issues of the Indo-Pacific. The identification of HRA, establishment of common SOPs and pooling of resources can play a decisive role in countering the various tame problems like piracy, terrorism and maritime crimes. On the other hand, the establishment of MPAs can help in forging a regional consensus on addressing IUU fishing which is a complex problem. Lastly, wicked problems in the region can be better managed through the deployment of coast guard assets in the contested maritime areas for avoiding geopolitical tensions and escalations between the claimant states. In the forthcoming months, the Quad can be expected to unveil a detailed roadmap elucidating the operational mandate for this initiative which is scheduled to begin from 2025 onwards.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “The Wilmington Declaration Joint Statement from the Leaders of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States”, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 21 September 2024.

- 2. Ibid.

- 3. “1st Coast Guard Global Summit”, Coast Guard Global Summit.

- 4. “Indian Maritime Doctrine”, Indian Navy, August 2009.

- 5. Ibid.

- 6. Sam Bateman, “Coast Guards: New Forces for Regional Order and Security”, East-West Center, January 2003.

- 7. Article 73, “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)”, p. 48.

- 8. Ibid.

- 9. Edward Sing Yue Chan and Douglas Guilfoyle, “Coast Guards’ Changing Nature: The Rise of the China Coast Guard”, in John F. Bradford, Jane Chan, Stuart Kaye, Clive Schofield and Geoffrey Till (eds), Maritime Cooperation and Security in the Indo-Pacific Region, Brill, 2023, p. 189

- 10. “Indian Maritime Doctrine”, no. 4.

- 11. Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century (Second Edition), Routledge, 2009, p. 315.

- 12. “Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy”, Indian Navy, October 2015.

- 13. Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century (Second Edition), no. 11, p. 286.

- 14. Ibid.

- 15. Joe Conroy, “Coast Guard Answers 9/11 Call”, US Naval Institute, November 2001.

- 16. “Operation Sovereign Borders”, Australian Government.

- 17. “Indonesia, Australia in High Seas Asylum Boat Stand-Off”, The Express Tribune, 8 November 2013.

- 18. “Memorandum of Understanding (MoU)”, Indian Coast Guard.

- 19. Abhay Kumar Singh, “India-Japan Strategic Partnership Imperatives for Ensuring ‘Good Order at Sea’ in the Indo-Pacific”, in Jagannath P. Panda, Scaling India- Japan Cooperation in Indo-Pacific and Beyond 2025: Corridors, Connectivity and Contours, Institute for Defence Studies & Analyses, 2019.

- 20. “UNCTAD’s Review of Maritime Transport 2022: Facts and Figures on Asia and the Pacific”, UN Trade & Development.

- 21. Abhay Kumar Singh, “India-Japan Strategic Partnership Imperatives for Ensuring ‘Good Order at Sea’ in the Indo-Pacific”, no. 19.

- 22. Ibid.

- 23. Sam Bateman, “Solving the Wicked Problems of Maritime Security: Are Regional Forums up to the Task?”, Contemporary Southeast Asia, Vol. 33, No. 1, April 2011.

- 24. Ibid.

- 25. Ibid.

- 26. Ibid.

- 27. Abhay Kumar Singh, “India-Japan Strategic Partnership Imperatives for Ensuring ‘Good Order at Sea’ in the Indo-Pacific”, no. 19.

- 28. Sam Bateman, “Solving the Wicked Problems of Maritime Security: Are Regional Forums up to the Task?”, no. 23.

- 29. Ema Septaria, “IUU Fishing in Indonesia, Are ASEAN Members States Responsible For?”, International Journal of Business, Economic and Law, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2016.

- 30. Sam Bateman, “Solving the Wicked Problems of Maritime Security: Are Regional Forums up to the Task?”, no. 23.

- 31. BIMCO, ICS, IGP&Clubs, Intertanko and OCIMF, “BMP5: Best Management Practices to Deter Piracy and Enhance Maritime Security in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea”, Witherby Publishing Group, June 2018.

- 32. Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century (Second Edition), no. 11, p. 293.

- 33. “The Wilmington Declaration Joint Statement from the Leaders of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States”, no. 1.

- 34. “Union Cabinet Approves India’s Signing of the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement”, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India, 8 July 2024.

- 35. Ibid.

- 36. “IUU Fishing in the Small-Scale Fisheries of the Western Indian Ocean Region”, Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association, August 2022.

- 37. Ibid.

- 38. Sam Bateman, “Coast Guards: New Forces for Regional Order and Security”, East-West Center, January 2003.

- 39. Ibid.