The Why and What of Non-Inclusivity and Dissensus in the Taliban ‘Emirate’

Summary

The Taliban has been most predictable in continuing with its fundamental ideological beliefs and convictions, as well as in implementing them, regardless of both domestic and international pressures. In many ways, the Taliban may be fundamentally all the same, but with time and experience, the more enterprising among them have effectively adopted the chicaneries of diplomacy and optics, publicity and propaganda, rhetoric and symbolism, denial and deception, and mixed messaging and strategic patience. The return of a larger, multi-generational and an all-Taliban ‘emirate’ to power in August 2021, with several interest groups and moving parts to it, was a consequence of a fragmented Afghan polity and geo-political play. With a State territory to itself, full access to the country’s natural resources, and several countries increasingly conferring proto-legitimacy to its ruling authority in Kabul, the Taliban apparently do not feel obligated to make political–ideological compromises under duress. Also, despite internal commotion and dissensus, there are no immediate ‘falling apart’ scenarios on the horizon.

Introduction

It has been over three years since the flag-bearers of the ‘Islamic Emirate’1 overran Afghanistan and walked into the capital Kabul in mid-August 2021, as the 17-year-old ‘Islamic Republic’ (2004–2021) lay trampled, disowned, and deserted. A sea of desperate humanity that had descended on the Kabul International Airport, seeking to escape the looming ‘Islamic Emirate’, not only symbolised the plight and flight of the ‘Islamic Republic’ but also the exodus of a whole new generation of educated and skilled Afghan workforce. With the country’s political and military leadership fleeing across the ancient Oxus, or Amu Darya, to the north, or to Pakistan in the east, Kabul’s capitulation to the forces of the ‘Islamic Emirate’ only seemed fated. For the Haqqani and Taliban fighters lying in wait, the takeover of the capital city turned out to be a surprise walkover, exceptionally non-violent and hassle-free. In sharp contrast to it, the exit of the Western forces was utterly chaotic, messy, and marred by violence. Even a giveaway deal that the United States (US) had signed with the Taliban at Doha in February 2020, failed to make the exit any less dishonourable.

The structural shift in the Afghan political landscape—from an ‘Islamic Republic’ to an ‘Islamic Emirate’, a fragile democracy to absolute theocracy, and from an all-inclusive multi-ethnic to a notably exclusive rural Pashtun clerical polity—was decisive and complete. Ironically, the US’ longest-ever overseas military mission, and also that of the transatlantic alliance, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), began with the overthrow of the first Taliban ‘emirate’ and ended two decades later with the instatement of the second Taliban ‘emirate’ in Afghanistan. In a way, the US and NATO-led coalition force, representing the world’s largest political and military alliance, handed over to the Taliban, all that it had taken away from them in the name of the ‘war on terror’ in 2001.

Emboldened by a historic sense of ‘victory’ over the West’s collective might, the Taliban felt entitled to reorder the Afghan State and society, as per their ideological conviction and political vision. Afghanistan was an open field for the Taliban. Much of the Taliban leadership felt under no obligation to make ideological compromises and political concessions under duress. The meetings that Haqqani and Taliban leaders held with former President Hamid Karzai, former Chairman of the High Council for National Reconciliation Abdullah Abdullah, and Hizb-e-Islami chief Gulbuddin Hikmatyar, who remained in Kabul and had formed a coordination council to facilitate a peaceful transfer of power to an inclusive interim/transitional administration, proved to be mere optics.2

The Taliban simply continued with its established political hierarchies and organisational structures, and also internal schisms and contradictions that came along, with the Amir-ul-Mumineen (leader and commander of the ‘faithful’) and his closed group of old clerics, advisors and confidants from the 1990s overseeing the Kabul affairs from Kandahar. Hibatullah Akhundzada, the Taliban’s current Amir-ul-Mumineen, has since increasingly asserted his role and authority across all organs of the interim government—political, military, judicial and administrative—down to the provincial and district levels, substantially limiting the scope and space for policy formulation and decision making at the level of the interim cabinet in Kabul. Similar to the first Taliban regime (1996–2001), the ultimate power and authority once again came to be effectively concentrated and vested in the Kandahar clique led by Akhundzada, who has been barely accessible and visible, even to the Taliban rank-and-file.

It was no surprise when two years later, the UN Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team concerning the Taliban in its 2023 report – which was said to be “the first in which the Taliban have been in power for the entirety of the reporting period” – observed that the Taliban has “reverted to the exclusionary, Pashtun-centred, autocratic policies of the Taliban administration of the late 1990s”. Commenting on the internal dynamic of the Taliban, the report pointed out that “Some dissent is apparent within the Taliban leadership, but the Taliban prioritize unity and the authority of the ‘leader of the faithful’ (Amir al-Mu’minin), which is increasing”, and assessed that “Cohesion is likely to be maintained over the next one to two years.” The report noted that Akhundzada “has been proudly resistant to external pressure to moderate his policies” and “there is no indication that other Kabul-based Taliban leaders can influence policy substantially.” The report saw “little prospect of change in the near to medium term”.3

On internal divisions, the report observed that “by reverting to uncompromising and autocratic leadership and Pashtun-centred policies remarkably similar to the political theology and behaviours of the Taliban in the late 1990s”, the Taliban chief Akhundzada “has also exposed divergent views within the Taliban” and that “these divisions are mainly between pragmatists wishing to demonstrate greater engagement and flexibility with the international community and archconservatives who maintain Deobandi theological beliefs, irreconcilable with various values and policies across the international community.” As for the commitments earlier made by the Taliban, the report noted that “Promises made by the Taliban in August 2021 to be more inclusive, break with terrorist groups, respect universal human rights, grant a general amnesty and not pose a security threat to other countries seem increasingly hollow, if not plain false, in 2023”.4

A year later, the UN Monitoring Committee in its report of July 2024 noted that the Taliban leadership “remains non-inclusive and predominantly Pashtun” and “the past year has seen the widespread imposition of Taliban policies and ideology, which are more narrowly defined than notions of Pashtun identity.” The report further noted that “Pashtun dominance is still causing stress within the social fabric of a multi-ethnic country”, resulting in “inevitable tensions between Pashtun Taliban groupings along tribal and political lines”. The report also observed that “Loyalty to, and alignment with, Hibatullah is now the defining factor in intra-Taliban tensions.”5

In the light of abovementioned observations, the study delves into the why and what of non-inclusivity and dissensus in the Afghan Taliban and its ‘emirate’. The study concludes with broad observations about the nature and conduct of the second Taliban regime.

The Broad Context

Afghanistan has been socially and politically agitated since the 1960s, and particularly following the overthrow of the constitutional monarchy in 1973. In the following years and decades, Afghanistan witnessed the rise and fall of disparate political systems and ideologies—violently imposed, and subsequently resisted and uprooted—creating complex, contradictory, and strong parallel impulses for modernism and conservatism. Such spectacular political shifts and alternating drives for rapid modern reforms and theological revivalism have not only precipitated the rural–urban divide, but also the identity politics and social polarisation in the country.

The Afghan Taliban had not appeared from nowhere in the mid-1990s. The founder members of the Taliban and their political ideology were rooted in the anti-Soviet and anti-communist ‘jihad’ of the 1980s in Afghanistan, which was wholly sponsored by the US-led Western Bloc and Saudi Arabia, and was fully supported by Pakistan, China and Gulf Arab States. Several founder and senior members of both the Taliban and the Haqqani Network had their militant political origins in the Pashtun resistance or ‘mujahideen’ parties, mainly the Harkat-e-Inqilab-e-Islami of Mohammad Nabi Mohammadi and Hezb-e-Islami (Yunus Khalis). Jalaluddin Haqqani, the founder of the Haqqani Network, too had fought under the banner of Hizb-e-Islami (Yunus Khalis). A few Taliban and Haqqani members were also known to have been earlier affiliated with the Ittehad-e-Islami of Abdurrab Rasool Sayyaf. The Taliban, whether in or out of power, have impacted the Pashtun landscape in Afghanistan and the adjoining Pashtun-dominated regions in Pakistan for almost three decades now, and several of its founder members have seen two superpowers humbled on Afghan soil.

The Afghan Taliban and their idea of ‘Islamic Emirate’, therefore, are a product and legacy, rather a manifestation of decades of systemic erosion of a unified Afghan State, of continued militarisation of society and weaponisation of religion, and the repeated failure of successive regimes to overcome their political–ideological ‘centralism’, often reinforced by ethnocentrism, and build sustainable State capacities down to the subnational levels. Successive Afghan regimes since the 1970s, including the first Taliban regime in the 1990s, have not been known to make timely course corrections, and the second Taliban regime seems to be repeating the same.

The August 2021 transition can also be seen as continuum in almost five decades of failed political transitions and experimentations with State (re)building in the country, interspersed with direct external political–military interventions, and involving three generations of Afghans. As a result, Afghanistan has emerged as a complex, multi-dimensional, and multi-generational challenge to the regional countries and to the international system. The recent developments in Afghanistan, therefore, need not necessarily be seen either in isolation or in immediate or fixed absolute terms—in black and white. Similarly, instead of being overly judgemental about the Taliban, it will be more expedient to look at its return to power and its internal dynamic, both in its own context and in the broad context of Afghanistan’s political and historical experience in the past five decades.

Taliban and Non-Inclusivity

After taking over the capital, Kabul, the Deobandi–Hanafi, madrassa-educated, and predominantly rural Pashtun Taliban soon set out to re-order the Afghan State and society, as per their interpretation and understanding of Islamic law and jurisprudence. Over the past three years, Taliban has resisted all calls to make their political set up ‘inclusive’, one that is representative of the country’s social–ethnic diversity, and remove social restrictions incrementally imposed on Afghan girls and women. The Law of Commandment and Prohibition (better known as the Vice and Virtue Law or the Morality Law), comprising four Chapters and 35 Articles, recently ratified by the Taliban chief Akhundzada in August 2024, is the strictest ever stipulation that virtually leaves no scope at all for women to have any public role.6 It is bound to widen the gulf between the Taliban regime and the people.

As expected, the Taliban leaders have resorted to their old and familiar tendencies to monopolise and over-centralise power and impose their theocratic worldview on a society that is inherently diverse and characteristically pluralistic in so many ways. It is also not a surprise that the people of Afghanistan, belonging to different ethnicities, speaking different languages, and following different social customs and cultural traditions, have not been at the centre of the Taliban’s overall thought process. Being a theocratic totalitarian regime, people’s will or choices and popular aspirations either do not matter or matter only to the point where it reinforces the Taliban ideology and its imagined constructs of a pure and truly Islamic rule.

Theocratic regimes, like the Taliban regime, tend to selectively idealise and amplify epochal events from a distant, and often imagined, historical past, viewing it as a golden period of pure timeless wisdom, worth emulating and instrumentalising in the contemporary environment, and consider recreating or reconstructing a social–political order based on it as a divinely ordained duty. A select interpretation, often literal, of religious concepts, doctrines and injunctions, backed by chosen historical references and past precedence, is politically instrumentalised and weaponised to self-legitimate the regime. The same is used to justify the regime’s efforts at institutionalising absolute political control and imposition of societal restrictions and regulations in the name of upholding religious, national or cultural values. The ideological custodians and the elite in such theocratic regimes consider masses as generally incapable of judging what is right or best for them, or for the society and the country, the thinking being that for lack of proper theological training and true understanding of religion and sacred scriptures, people are assumed to be cognitively and intellectually incapable of finding the ‘true path’ to righteousness and piety. That is something to be told, taught, and if required forcibly and harshly imposed in the name of bringing ‘peace’ and ‘stability’ to the country, or restoring national and cultural pride, and which is possible only by way of establishing a ‘strict, pure and genuine religion-based political system’. All impositions are decreed and justified on the pretext of protecting the ‘interests of the people’ or promoting the ‘welfare of the people’, and following the ‘God’s Will’.

Most of the Taliban leaders, and particularly a section of the relatively younger leaders, mostly schooled, indoctrinated and nurtured in well-financed Pakistani jihadi madrassas7 that came up in the 1980s and 1990s, appear clear about their political and social objectives, which is to alter the very characteristics of the Afghan polity, and which cannot be achieved without reordering or replacing all that existed before. It is not limited to simply ridding society and politics of any perceived Western or un-Islamic influences. Even the centuries-old indigenous social–religious identities and traditions at local levels, and the cultural diversity it brings to the ways of Afghan life, are seen as irritants or impediments to establishing ‘a truly Islamic system’. That explains the Taliban’s ideological and social–political aversion (or for that matter of any ethnocentric or Islamist totalitarian regime) to making their top political and military leadership structures socially or politically ‘inclusive’, ‘participatory’, or ‘representative’ by way of bringing in ‘the uninitiated non-madari elements’ either from the previous regime or from outside the rank-and-file. And that further explains the totality of Mullah–Mawlavi component to the Taliban leadership structures at all levels.

Although predominantly ethnic Pashtun, the Taliban regime has not been able to integrate even the non-Taliban Pashtuns. An effort was made by a section of the Taliban leadership that led the negotiations with the US in Doha to explore the prospect of having some non-Taliban representation in the interim cabinet. However, the whole idea of having an ethnically inclusive interim government simply vanished with the fall of Kabul and the complete withdrawal of Western forces by the end of August 2021. The Taliban had stated on several occasions over the past decade that they do not seek to monopolise power and would establish an inclusive Islamic government. The Taliban had made such claims in the 1990s as well. The appointment of a few non-Pashtun Taliban members at relatively high positions in the interim cabinet was more in continuation of their roles from the previous Taliban regime, and thereafter, from the commissions formed during two-decades of exile (2001–2021). Their reappointment in the current Taliban interim cabinet, therefore, marked a continuity and not any fundamental shift in the Taliban’s position when it came to appointments at consequential senior-level civil and military positions.

In the 33-member all-male, all-Taliban caretaker/interim cabinet announced on 7 September 2021—that included a prime minister and two deputy prime ministers, 19 cabinet ministers, five deputy ministers, and appointees to key institutions such as the intelligence, army, and the central bank—there were only three non-Pashtun members occupying senior positions.8 The first was the Acting Second Deputy Prime Minister for Administrative Affairs Mawlavi Abdul Salam Hanafi, an ethnic Uzbek from Darzab District, which was earlier in Faryab Province and was latter incorporated in Jowzjan Province in northwestern Afghanistan. Hanafi had served in various capacities in the education ministry in the first Taliban regime. Post 2001, he served in the Taliban political commission and was later inducted into the leadership council. He was also a part of the 21-member Taliban negotiating team in Doha. The second member was the Acting Minister of Economy Qari Din Mohammad ‘Hanif’, an ethnic Tajik from Yaftal Sufla District of Badakhshan Province in northeastern Afghanistan. Hanif served as the planning minister and higher education minister in the first Taliban regime. Post 2001, he served in the Taliban political commission and was later inducted into the leadership council. He too was a part of the 21-member Taliban negotiating team in Doha. The third member was the Taliban Chief of Army Staff, Qari Fasihuddin ‘Fitrat’, an ethnic Tajik from Badakhshan Province, who earlier served as the shadow governor of the province and commander of the Taliban forces in the northern front and as the deputy leader of the Taliban military commission headed by Mawlavi Mohammad Yaqoob. There was not a single ethnic Hazara, Afghanistan’s third largest ethnic group, or any Shia representation at senior levels in the interim cabinet. Of the 33 appointees, over a dozen were on the UN sanctions list, and at least four were former Guantanamo Bay detainees.9

Two weeks later, on 21 September 2021, the Taliban expanded the interim cabinet to add 17 more members—including two acting ministers, 12 deputy ministers, and heads of key national institutions such as the National Olympic Committee, National Statistics and Information Authority, and the Nuclear Energy Agency, taking the total strength of the interim government to 50 members.10 It was an attempt at internal balancing and at giving some representation to non-Pashtun Taliban members and technocrats at subordinate levels in the interim government. The appointment of two veteran military commanders, Mullah Abdul Qayyum Zakir as second deputy defence minister and Mullah Ibrahim Sadr as deputy interior minister for security affairs, both of whom could not be accommodated in the first phase of the cabinet formation, was a significant development. Both had joined the Taliban in the 1990s and played a significant role in the expansion of the Taliban military power over the past two decades. Both were known hardliners and served as deputies to Mawlavi Yaqoob who headed the Taliban military commission. The expanded cabinet also saw the appointment of a few professionals, including the acting minister of public health, Qalandar Ebad, a physician, and his two deputies, one an ethnic Uzbek and the other an ethnic Hazara. However, Ebad, who was perhaps the only technocrat holding a cabinet level position, was removed from his post in May 2024 and was replaced by a cleric and the then deputy administrative head in the interior ministry, Mawlavi Noor Jalal Jalali.11

The scenario at provincial levels was no different. According to the UN sanctions monitoring team’s June 2023 report, 25 out of 34 Taliban provincial governors were Pashtuns.12 The simmering tension between Pashtun and non-Pashtun Taliban officials and commanders particularly in the northern provinces often led to violent confrontations. There have been reports about land being usurped from non-Pashtuns for redistribution among Pashtuns in the northern and central parts of the country. Similarly, there have been reports about Pashtuns being resettled in certain areas affecting the local demography. It can be seen as a kind of Pashtunisation of critical resources in predominantly non-Pashtun regions. Perhaps, it is in continuation to what Amir Abdur Rahman Khan had started over a century ago in the 1890s, and which the Taliban had attempted a century later during its first regime in the 1990s.

The events leading to the announcement of the Taliban caretaker cabinet in early September 2021 suggested that there were serious differences within the Taliban, particularly between Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, representing the old Kandahari network within the ‘emirate’, and Sirajuddin Haqqani, Khalifa of the much older network from the 1980s, on the allocation of key portfolios.13 Since it remains a sensitive and conflicting issue, the Taliban’s priority has been to make the cabinet and the regime internally inclusive, in terms of accommodating various Pashtun constituent groups and stakeholders claiming credit for the ‘victory’.

This was not the first time when groups within the Taliban had turned on each other. In December 2015, there were reports of violence during a high-level Taliban meeting held in Quetta, in which the then Taliban Amir, Mullah Akhtar Mansour, was reportedly injured.14 Prior to that, there have been several reports of serious differences emerging between the leadership of the Taliban military and political commissions, and among senior Taliban military commanders, many of whom were acting independently of the political leadership. Political crises within the Taliban leadership structures had emerged following the detention of deputy leader Mullah Baradar from Karachi in February 2010, and thereafter in 2015, when the issue of leadership succession came up following confirmed reports about Mullah Omar having died two years ago in 2013.

Soon thereafter, in 2016, the Head of the Taliban political office in Doha and a close aide of Mullah Omar, Tayab Agha, resigned from his position owing to differences with the new Taliban chief Mullah Akhtar Mansour. After Mansour was killed in May 2016 and Akhundzada took over as the new chief, and as the Taliban expanded their military footprint inside Afghanistan, the two deputy leaders, Mawlavi Yaqoob (son of Mullah Omar) and Sirajuddin Haqqani (son of Jalaluddin Haqqani), came to play a key role in shaping the Taliban’s operational strategy. In his email interview to the RFE/RL in early August 2021, Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid had informed that Mawlavi Yaqoob was in-charge of 13 provinces in the ‘western zone’, comprising mainly of southern and western regions, and Sirajuddin Haqqani was in-charge of 21 provinces in the ‘eastern zone’, mainly eastern and northeastern regions including the Kabul Province.15

On the face of it, the distribution of power ministries among key constituent groups, including the Haqqanis, appeared to have been a big a challenge for the Amir-ul-Momineen and his council of confidantes to handle, so much so that the then ISI chief, Lt Gen Faiz Hameed, had to visit Kabul. Upon his arrival in Kabul on 4 September, the ISI chief was quoted to have stated in response to a question from a journalist: “Don't worry, everything will be okay”.16 Three days later, on 7 September, the Taliban finally announced the 33-member interim cabinet, with the powerful interior ministry going to Sirajuddin Haqqani. Khalil-ur-Rehman Haqqani, Sirajuddin Haqqani’s uncle, was appointed the Minister of Refugees and Repatriation, and Mullah Taj Mir Jawad, who led the ‘Kabul Attack Network’ and was considered close to the Haqqani Network and Pakistani intelligence, was appointed as the first deputy director general in the Taliban’s General Directorate of Intelligence.

The highly publicised visit of the ISI chief – very unusual for visiting intelligence chiefs – coming amidst a sense of déjà vu in both Rawalpindi and Islamabad over the fall of Kabul, was preceded by celebrations across several jihadi seminaries in Pakistan and among Pakistan’s feudal Punjabi elite, and not to be left behind, the radicalised sections among both the urban middle and lower middle class. Anyone with an understanding of the history of Afghanistan, and particularly the nature of social and political dynamics that the Pashtun Taliban represented, would have known that any jubilation over the fall of the State and the economy in Afghanistan was bound to be short-lived.

One wonders if a crisis situation was created or used to make space for the Pakistan intelligence to directly intervene in the formation of the Taliban cabinet in favour of its closest ally within the ‘emirate’, and also to project itself as the ‘political manager’ of the Afghan Taliban. Was it a deliberate ploy to gain optics and send across the message that Pakistan remains the via media for the international community to engage with the new regime in Kabul, or was it meant to expose limitations of the top Taliban leadership in terms of managing its affairs independently? As expected, the attempted handholding of the Afghan Taliban by Pakistan establishment has since backfired.

Whichever way one looked at the powerplay that unfolded in the run-up to the formation of the caretaker cabinet, it reflected poorly on Hibatullah Akhundzada’s leadership. It exposed the first major chink in Akhundzada’s supremacy. The second big chink was exposed less than a year later in July 2022, when al-Qaeda chief Ayman al-Zawahiri was killed in a US drone strike at a safe house in Kabul. It was said that the safe house belonged to a close aide of Sirajuddin Haqqani. The third and most recent challenge to Akhundzada’s supremacy came when some senior members of the Taliban interim cabinet, particularly Acting Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani and Acting Defence Minister Mohammad Yaqoob, openly expressed criticism over attempts to monopolise power and emphasised the need to respond to the legitimate demands of the people.

In his opinion piece published in The New York Times just over a week before the signing of the Doha Agreement in February 2020, Sirajuddin Haqqani had stated:

We are committed to working with other parties in a consultative manner of genuine respect to agree on a new, inclusive political system in which the voice of every Afghan is reflected and where no Afghan feels excluded. (emphasis added)I am confident that, liberated from foreign domination and interference, we together will find a way to build an Islamic system in which all Afghans have equal rights, where the rights of women that are granted by Islam—from the right to education to the right to work—are protected, and where merit is the basis for equal opportunity. (emphasis added)

If we can reach an agreement with a foreign enemy, we must be able to resolve intra-Afghan disagreements through talks.17 (emphasis added)

A year later, in March 2021, Sirajuddin Haqqani in a speech delivered at an assembly of mujahideen, had expressed concerns over the ongoing tension among commissions within the ‘emirate’. He had stated:

…the beginning of the ongoing jihad was done with sincerity and pure intentions because at that time there were no material incentives, responsibilities or positions of power…Everyone considered jihad a divine responsibility regardless of what would happen next, success or failure. There was only a wave of passion that we would do our Islamic duty (jihad) before considering anything else…Therefore, at that time no one even imagined ideological differences and issues. Of course, after the expansion of responsibilities and positions, some issues naturally came to forefront. These issues arose because I think there was a difference in intentions. (emphasis added)But unfortunately, I have to say that sometimes I feel that the spirit of coordination and mutual understanding between our commissions is fading, or in other words, sometimes one commission considers itself against another commission as one state against another, or as one party is at a distance from the other. All our commissions should work together in coordination, unity and cooperation and lend a helping hand to each other…If we see harm anywhere, instead of promoting it, airing it, spreading it, confusing people’s minds and turning it into a point of discord, we need to research and find answers. (emphasis added)

Instead of propagating against each other and conspiring, we must keep all the departments of the Emirate united and support them in every possible way as we consider ourselves servants in the service of the colleagues of each department.18 (emphasis added)

Haqqani concluded his speech exhorting the need to “make a solemn promise not to hurt the people”, not to act in a manner that “frightens the people” or makes the Taliban “look unaccountable”. He also exhorted the need to “respect the people’s opinion on every issue”.19

In early February 2023, while addressing a gathering in Khost, Haqqani reportedly stated that, “Power monopolization and defamation of the entire system have become common. The situation cannot be tolerated any longer.” He added:

The survival of the government depends on how we treat the people. The previous government was corrupt and did not survive because it repressed and ill-treated people. If we treat people well, our government will last longer.20

Similarly, on 15 February 2023, on the 34th anniversary of the Soviet withdrawal, Acting Defence Minister Mawlavi Yaqoob reportedly stated:

We should always listen to the legitimate demands of the nation and try to gather this nation around us and then we and our nation will cooperate in every development, and will progress and prevent any possible disaster and not become a victim of the evil goals of foreigners.21

He added:

We reached our goals with many sacrifices. Now, the responsibility has been placed on our shoulders and it requires patience, morals, and proper behavior and engagement with the people.22

Speaking on the occasion, Acting Minister of Mines Shahabuddin Delawar also reportedly stated that, “A minister, a governor, a district governor, a judge, or whoever it is---must support the legitimate demands of our people.” He is said to have further stated that, “freedom is achieved through the power of the general public and lost by leaders. Maintaining freedom is equally important as gaining it.”23

Three months later, in May 2023, on the 10th death anniversary of the Taliban founder Mullah Omar, Sirajuddin Haqqani stated:

We should not monopolize the government and make it small so that only individuals from our religious seminaries see themselves involved in it. Everyone is part of this government…The government was not established to save only ourselves but it was established to rescue the country.24

In March 2022, the Taliban interim cabinet announced the formation of a seven-member commission called Ertibatat Ba Shaksiat Hai Afghan Wa Awdat Ananfor or ‘Commission for Contact or Liaison with Afghan Personalities and their Return’. It is headed by veteran Taliban leader and acting minister of mines and petroleum Shahabuddin Delawar. The other six members of the commission are: Amir Khan Muttaqi (acting foreign minister), Khairullah Khairkhwa (acting minister of information and culture), Mohammad Khalid Hanafi, Abdul Haq Wasiq (the intelligence chief), Fasihuddin Fitrat (chief of army staff), and Mohammad Anas Haqqani (younger brother of acting interior minister Sirajuddin Haqqani).25 According to the Taliban statement issued on the occasion, “The commission will liaise with Afghans who have left the country so that they can return to their homeland and live in peace with their Afghan brothers instead of foreign countries.”26 The commission was part of the Taliban’s effort to make the ‘emirate’ appear inclusive in its approach.

To offset international criticism for not being inclusive, the Taliban’s leaders continue to reiterate the retention of 500,000 employees, mostly at lower levels in districts and provinces, from the previous government. The Taliban also refer to the presence of some women employees in the field of health, education, and in the interior ministry. They had made similar concessions in the 1990s. The Taliban website claimed in December 2023 that about 150,000 female personnel were employed in the health and medical sector, and thousands of destitute women were supported and provided salaries in certain provinces.27

The Taliban’s announcement of ‘general amnesty’ for those who served under the previous government was also not new. Long before 2021, the Taliban had announced amnesty for government officials and security personnel willing to join its ranks.28 The first Taliban leader Mullah Omar established a separate commission for the purpose in 2011 under the supervision of the current leader Hibatullah Akhundzada. Later, when Akhundzada took over the leadership of the Taliban in 2016, the commission came to be supervised by Mullah Abdul Manan Omari, one of Mullah Omar’s brothers and member of the Quetta Shura.29

However, despite the Amir-ul-Mumineen announcing a general amnesty in the immediate aftermath of the fall of Kabul in August 2021, there were reports of the Taliban forces targeting members of the Afghan armed forces and the pro-government militias in several parts of the country. Within a month of the Taliban assuming power, Acting Taliban Defence Minister Yaqoob had to issue an order in September 2021, forbidding the Taliban forces from carrying out revenge killings against members of the previous regime, even in case of personal rivalries and enmities.30 The Taliban has frequently countered the demand to make their governing structures inclusive and representative, stating that it is not clear as to what the international community means by an inclusive government.31

Although the Taliban have been in power for over three years now, the internal functioning and dynamic of the ‘emirate’, and the core decision and policy making processes, centred away from Kabul in Kandahar, still remain somewhat shrouded, as it was when the leadership was exiled in Pakistan. There have been numerous reports of internal dissensus within the ‘emirate’, which perhaps provides some insight into the internal dynamics and the subtleties of the emerging powerplay, primarily between pro-changers (not necessarily pro-reform), seeking issue-based policy reconfiguration to keep pace with the requirements of time and circumstance, and no-changers, emphasising strict literalist interpretation and implementation of Sharia and Hanafi jurisprudence. The latter projects Sharia-based rule as a source of stability and unity and panacea for all ills.32 However, there are voices within the ‘emirate’ that seek a more worldly approach to deal with the challenges of State governance and integration of the regime into the international system.

The sidestepping of one of the seniormost Taliban leaders, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, who led the negotiations and signed the Doha Agreement with the US, and assured the international community of an inclusive Islamic government that would protect the rights of women and minorities, strengthened the hands of the old unworldly Taliban ideologues bent on repeating the mistakes of the 1990s. Interestingly, Baradar, after his release from the Pakistani detention in October 2018, was reappointed by Akhundzada as the deputy leader for political affairs in January 2019, the position he held prior to his detention in February 2010, and the head of the Taliban political office in Doha.33 Over the past three years, since the formation of the interim cabinet in September 2021, Baradar has refrained from publicly articulating his position on contentious matters, and has limited his role and engagements to only economic affairs. The acting deputy foreign minister, Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanekzai, who earlier headed the Taliban political office in Doha and was actively involved in negotiations with the US, too has been marginalised.

The pushback against sharing power with the non-Pashtun factions from the north or having political elements from outside, including the non-Taliban Pashtun leaders, or allowing women to have a role in public life, had always been there within the Taliban. Akhundzada in his first Eid-ul-Fitr message issued in July 2016, in his capacity as the new Amir-ul-Mumineen, had reiterated his commitment to establishing a Sharia-based political system in the country, which largely ruled out the possibility of any power-sharing arrangement with the incumbent Ashraf Ghani Government in Kabul. He had also reiterated the Taliban’s long-held policy of granting rights to women within the framework of Sharia.34 Akhundzada has largely continued with the policies from the late 1990s, with Sharia as the law and source of all authority. Five years later, following the announcement of the caretaker/interim government in early September 2021, Akhundzada stated:

Our previous twenty years of struggle and Jihad had had two major goals. Firstly to end foreign occupation and aggression and to liberate the country, and secondly to establish a complete, independent, stable and central Islamic system in the country.Based on this principle, in the future, all matters of governance and life in Afghanistan will be regulated by the laws of the Holy Sharia.35

The Taliban, being militant Sunni Islamists, never had Shias and women holding positions in its organisational structures in its past three decades of existence. Although there have been non-Pashtuns in the Taliban rank-and-file since the 1990s, including as members in the Rahbari Shura or the Leadership Council that was established in Quetta in 2002–03, they hardly ever had any decisive role in the core policy or decision-making processes. Perhaps, more non-Pashtun clerics, commanders and fighters joined the Taliban when it opened a northern front against the NATO-led ISAF deployed in the region. These Tajik and Uzbek commanders and fighters later strengthened the Taliban position in the northern provinces, particularly against the Uzbek Jowzjani and Tajik Jamiati militias dominating the region. It was the Taliban’s senior Tajik commander and presently the chief of army staff, Qari Fasihuddin Fitrat, who had played a key role in the fall of the northern provinces in early August 2021.

With several groups competing and clamouring for a larger share of power in the interim Taliban government, there was not much scope left for the inclusion of the non-Taliban elements. The emphasis has since been on managing internal discords and divisions through compromise and accommodation, to maintain the unity of the rank-and-file. Even otherwise, the Taliban have not been known to co-opt elements from other Afghan groups, including ‘mujahideen’ leaders and former government officials. Their relations even with their allies, al-Qaeda and the Haqqani Network, have not always been smooth. The Taliban and al-Qaeda do not even share a common ideology or objectives, and despite Sirajuddin Haqqani holding senior leadership positions within the Taliban since mid-2015, the Haqqani Network has maintained its independent political–military structures, including units of suicide bombers, and never practically merged with the Taliban.

What is notable is that despite decades of relationship with al-Qaeda, the Afghan Taliban have maintained their distinct political identity and ideological agenda, which is largely limited to Afghan and Pashtun geography, and have avoided getting subsumed, ideologically and materially, into the politics and business of global jihad.

Dissensus in ‘Emirate’

The Taliban has outwardly been clear about the role and position of the Amir-ul-Mumineen in the overall leadership structure of the ‘emirate’, whereby the Amir has been vested with absolute authority. Hibatullah Akhundzada is projected as the undisputed supreme leader, who is supposed to be beyond the pale of public view and scrutiny. He is neither to be seen nor to be directly spoken to or photographed. Only a chosen few have access to him. He cannot be seen as socialising with common men, and certainly never with women, and not even all sections of the Taliban rank-and-file. He is also not supposed to give interviews or directly interact with the media, and it is only in the rarest of circumstances that he would ever meet visiting foreign leaders, and only if ‘he’ is a Muslim from an Islamic country.

An element of mystery and aura surrounds him and his very existence, and similar to the first Amir, Mullah Mohammad Omar, Akhundzada’s authority flows from Kandahar—the historical and spiritual seat of the Pashtuns. His decrees and directives, written or verbal, are not to be questioned or challenged. Akhundzada works through a closed group of clerics of his ilk, basically a coterie or clique, and keeps a close watch on all activities and functions of the interim cabinet and the military through a network of loyal confidants assigned to all organs of the interim government. Akhundzada’s role and position in the Taliban hierarchy and his style of functioning does not seem to be any different from that of Mullah Omar, the founder chief of the Taliban. Mullah Wakil Ahmad, Mullah Omar’s close confidant and official spokesperson, had reportedly stated in October 1996 that:

Decisions are based on the advice of the Amir-ul Momineen. For us consultation is not necessary. We believe that this is in line with the Sharia. We abide by the Amir's view even if he alone takes this view. There will not be a head of state. Instead there will be an Amir-ul Momineen. Mullah Omar will be the highest authority and the government will not be able to implement any decision to which he does not agree. General elections are incompatible with Sharia and therefore we reject them.36

It is noteworthy that in April 2023, Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid was ordered to shift his office from Kabul to Kandahar.37 To extend his authority at the subnational level, Akhundzada has formed joint councils of scholars and clerics, or Ulema Councils, in the provinces, which provide ideological and policy guidance to the Taliban officials down to the district and sub-district levels. In his message issued in April 2023, it was stated that these councils have been formed for:

…monitoring the work of the provincial offices, providing written and verbal advice on religious matters, observing the behaviour of the officials, sharing shortcomings with concerned people in a proper manner as well as building and maintaining relations between officials and the public.38

In May 2023, Zabihullah Mujahid stated that the Ulema Councils have been established in more than 18 provinces and that these councils have “an important role as a bridge between the people and government.” He added that with the establishment of these councils “justice will be guaranteed” and “the voice of the people will be conveyed to the government and the plans of the government will be conveyed to the people.”39 By September 2023, the Ulema Councils had been established in all 34 provinces of the country.

In August 2023, the Ulema Council of Kabul held a jirga, a large gathering of religious scholars, clerics and elders from the capital province, in which a 12-point statement was issued. At the end of it, the jirga urged the Taliban officials to fully implement all the decrees and commands issued by the Taliban chief Akhundzada and deal seriously with the violators. It also renewed its allegiance to Akhundzada. Senior Taliban ministers, including Acting Foreign Minister Muttaqi, and Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani, addressed the jirga.40

While there has been dissensus among sections of the Taliban leaders regarding certain decrees or policy proclamations issued by Akhundzada, overriding the decisions of the interim cabinet based in Kabul,41 nevertheless, the supreme authority of Akhundzada is unlikely to be directly challenged at least in the near to short-term. However, the same cannot be ruled out in the long-term, as differences between Kabul and Kandahar deepen. In the absence of collective consensus, or persistent dissonance on issues considered critical to securing international recognition for the regime, sections of the Taliban leadership are likely to express criticism from time to time, indirectly questioning Akhundzada’s decisions. That explains Akhundzada’s thrust on conveying opinions and views in private and not publicly.

After Sirajuddin Haqqani had spoken against the monopolisation of power in early February 2023 in Khost, Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid had issued a long statement:

The manner of criticism, in accordance with ethical guidelines, is that if someone has a criticism of the emir (leader), a person in charge, minister, deputy minister, or director—Islamic ethics suggests that it is better to not denigrate him, and to respect his dignity. Through a safe, discreet and protected manner, approach him so that no one else will hear, and then mention the criticism.42

Later, in April 2023, Akhundzada in his message to the people stated:

If someone wants to advise the leader, he advises him secretly, because secret advice is useful, do not give open advice, because open advice has negative effect instead of positive.43

Given the apparent disquiet among sections of the Taliban leadership in Kabul—representing different interest groups that have emerged over the last few years, and are perceived as more enterprising and growing in ambition—over certain policy decisions, including on the issue of female education and employment, Akhundzada has been trying to strengthen his reach and authority to all sections of the caretaker/interim government in Kabul. While looking at dissensus, and not necessarily irreconcilable divisions at this juncture, against the theological rigidities of the Amir-ul-Mumineen and his appointees, many of whom now occupy influential positions, particularly in the ministries of justice, higher education and finance, one has to factor in the generational shift taking place, and with it the resultant competition between the older and the younger leadership to consolidate and broaden their respective networks and spheres of influence.

In the last three years, Akhundzada has increased his interaction with members of the interim cabinet, military commanders, and provincial officials. He has been appointing and reappointing people in the cabinet and at other senior level positions, including at provincial levels, and in areas traditionally considered strongholds of the Haqqani Network. In May 2023, he replaced Prime Minister Mullah Hassan Akhund, who reportedly had not been keeping well and had been missing from action, with Deputy Prime Minister for Political Affairs Abdul Kabir, apparently on an interim basis. However, in the last few months both have been taking turns to preside over meetings, including with the visiting foreign leaders and representatives. The new Chinese Ambassador had presented his credentials on 13 September 2023 to Hassan Akhund and not Kabir, who was not present in the ceremony held on the occasion.44 In August 2024, he for the first time met the governors all provinces in Kandahar.45 The next month, in early September, he undertook a 14-day tour to the northern and northwestern provinces. He was said to have visited Herat, Badghis, Faryab, Jawzjan, Sar-i-Pul, Balkh, Samangan, Baghlan, Kunduz, Takhar, and Badakhshan. He was also said to have visited three regional corps of the Taliban armed forces, including Al-Farooq, Al-Fath, and Al-Umari.46

Earlier, in October 2023, Akhundzada had appointed the former governor of Helmand Province and commander of the Taliban suicide squad ‘Omari’, Mawlavi Abdul Ahad, also known as Mawlavi Talib, as commander of his special forces. It is said that Akhundzada has created a separate force of about 40,000 personnel for his own security. In March 2023, former Afghan intelligence chief Rahmatullah Nabil claimed that about 60 billion Afghanis, drawn from the Taliban-led finance ministry’s budget, were spent over the past year on Akhundzada’s special force.47

At the end of March 2024, Akhundzada’s purported audio message was posted online in which he spoke about restoring punishments such as the stoning and flogging of women for adultery and immodesty, as per the Sharia. According to the reports, he stated:

Now we will practically implement Sharia. We will enforce Allah’s hudud…You might say this violates women’s rights if they are stoned. Soon, we will implement the punishment for adultery and publicly stone women; we will publicly flog women. These actions are contrary to your democracy, and you will debate them. You also claim to fight for humanity; I claim the same.48

Mullah Nooruddin Turabi, who was justice minister and headed the ministry for propagation of virtue and prevention of vice in the first Taliban regime in the 1990s, had stated in September 2021 that public punishments and executions based on Sharia will be implemented, and warned the international community against interfering with it. He asserted that, “No one will tell us what our laws should be. We will follow Islam and we will make our laws on the Quran.” Interestingly, arguing that the Taliban have “changed from the past”, he rationalised the Taliban decision to allow the use of television, mobile phones, photos and videos stating that it would help the regime in disseminating its message and deter the people from violating the Islamic law.49

Post August 2021, while there have been regular reports of men and women being sentenced to public flogging for alleged adultery and other crimes, there have hardly been reports of women being sentenced to public stoning.50 However, there have been reports of public executions. The Taliban had executed five men until early 2024, for allegedly committing murders. All the five public executions were ordered by the Taliban courts and were approved by Akhundzada. The first public execution was carried out on 7 November 2022 in the southwestern Farah Province, the second on 21 June 2023 in the eastern Laghman Province, and the third and fourth together on 22 February 2024 in the southeastern Ghazni Province.51 The fifth public execution was carried out immediately thereafter on 26 February 2024 in the northern Jowzjan Province.52 Despite the new Constitution of 2004 guaranteeing equal rights to both men and women, the state and condition of women in the vast rural areas of the country had not seen any notable improvement under the previous regime. The return of the Taliban to power with their anomalous interpretation of Sharia had only worsened the condition of the Afghan women, with no reprieve at all in sight in the foreseeable future.

Theological conservatism has long helped the Taliban ideologues, most of whom are not adept in the conduct of economic, political and diplomatic affairs—and thereby are least qualified to run the affairs of the State—in spawning their hold and control over the political and military leadership, that tends to acquire its dynamics. Now that the Taliban has a territory to itself and seeks ‘normalisation’ of relations with the outside world, any absolute monopolisation of power by the Amir-ul-Mumineen and his cohorts is bound to spawn resistance from sections of the political leadership operating from Kabul. Similarly, the ideological core too will attempt to rein-in any display of independent dynamism or accumulation of power, whether at national or subnational levels. The internal powerplay to rebalance power distribution is likely to gain traction when the issue of succession to the current Amir-ul-Momineen comes up in future.

Compared to the first Taliban regime of the 1990s, the Taliban that returned to power in 2021 was a much larger entity and with several constituent groups, the Haqqanis being the most prominent among them. Pashtuns are not just the largest but also internally the most segmented and diverse ethnicity in Afghanistan. With time, the pulls and pressures, the interplay of centrifugal and centripetal tendencies, will likely gather pace, particularly as the broader intra-Pashtun dynamics come into play, with the predominantly Pashtun ‘Islamic State Khorasan’ (ISK) very much a part of it.

Concluding Observations

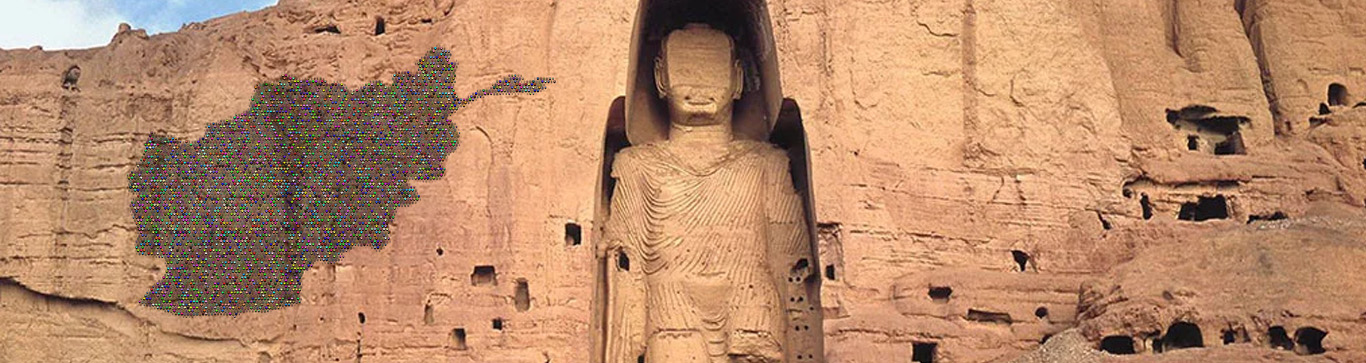

While there does not seem to be any fundamental shift in the ideology of the Taliban, its strategies/tactics have evolved, especially its media and communications strategy, in terms of public outreach through various fora, including social media. The Taliban has engaged media influencers, particularly YouTubers, to boost their image. Similarly, the Taliban has been promoting and projecting tourism as an indicator of security and normalcy in the country.53 Unlike in the 1990s, the Taliban now appear better sensitised about the need to protect and preserve historical artefacts, including the pre-Islamic cultural heritage of the country.

The Taliban leadership may not fully understand the complexities of statecraft and governance, but they do seem to understand the politics of international and economic diplomacy. The Taliban has sought transactional relationships with countries on a reciprocal basis, to safeguard their regime’s sovereign autonomy. The Taliban regime is presenting and projecting itself as ‘an opportunity’ and ‘a willing partner’ for the region to realise its economic potential; and going forward, as ‘security providers and guarantors’ for trans-regional connectivity ventures via Afghanistan.

Despite expressing serious concerns over the Taliban regime’s domestic policies, particularly severe restrictions imposed on women, including the closure of the Ministry of Women’s Affairs and the restoration of the Ministry for Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice (officially, Ministry of Promoting Virtue, Preventing Evil, Summoning and Hearing Complaints), and the failure to meet known and unknown commitments made to the US in Doha in February 2020, the international community has incrementally engaged the Islamist regime in Kabul.

The Taliban takeover was neither welcomed nor challenged by the Afghan people in general, and similar to the previous Afghan regimes, except that of Karzai and Ghani, the Taliban regime too was not chosen by the people to lead the Afghan nation. In the last few years, the Taliban has hardly been a pariah to most of the regional countries, and also to some extent to the international community, even as most of its senior members remain under the UN sanctions.

According to the latest July 2024 report of the UN Sanctions Monitoring Team, there were at least 61 sanctioned members associated with the Taliban interim government. Of the 61 sanctioned members, 35 held cabinet-level positions, including the prime minister and three deputy prime ministers. Among the remainder, the report stated that 14 were acting ministers and seven had roles that combined business functions with advisory activity. Given the continued preponderance of the Pashtun Taliban in the interim government, of the 61 sanctioned members, 55 were Pashtuns, four were Tajiks and two were Uzbeks.54 It is noteworthy that the number of sanctioned Taliban members serving or associated with the interim government has only increased over the past three years, from 41 as per the May 2022 UN sanctions monitoring team report to 58 as per the June 2023 report to 61 as per the latest July 2024 report.

In the long term, whether the Taliban can bear the weight of State and governance, and the various responsibilities and obligations that come with it, is something that remains to be seen. It appears that sections of the Taliban leadership realise that the window for ‘normalisation’ of relations with the outside world may not remain wide open for too long. At the domestic level, a prolonged and complex humanitarian crisis, compounded by series of devastating natural disasters, leaving thousands of people displaced, and the return of over a million Afghans from Pakistan and Iran; lack of international aid and investment; banking and liquidity crisis; widening trade deficit and rising price levels; limited economic and revenue base; and increased threat from ISK could prove to be a major impediment to efforts at regime consolidation. While the old political opposition remains divided and exiled, the activities of predominantly Tajik resistance groups—particularly the National Resistance Front and the Afghanistan Freedom Front—have been limited to sporadic incidents of low-level targeted attacks outside the cities. In the absence of external support, these groups are in no position to pose any existential threat to the Taliban regime. However, Afghanistan being a landlocked country has its geopolitical and geo-economic vulnerabilities, and the Taliban resources might be stretched thin.

The security landscape from the Taliban’s point of view seems stable for now, but the presence of various foreign Islamist groups with transnational agendas could prove to be a major spoiler in the Taliban’s efforts at cultivating ties with its notably diverse neighbourhood. The decades-old symbiotic linkages among these militant Islamist groups, and theirs with the Taliban, are a double-edged sword. If they are an asset to the Taliban regime, providing the latter with potential leverages vis-à-vis the neighbours, their presence and actions can prove to be counter-productive for the Taliban regime in the long term. Now that the Taliban are centred to the west of the Durand Line, the threat to their regime in Kabul may not be as much from within Afghanistan as from across the Durand Line, and from big power rivalries in the region. Afghanistan has long been a battleground of larger geopolitical play, and the return of the Taliban and its ‘emirate’ to power is a product and continuum of it.

Compared to the 1990s, the Taliban has been far more diplomatic and tactful in dealing with the outside world this time around. Its spokespersons until at least 2022–23 appeared sensitised about the need to manage external perceptions about the regime. The Taliban has been capitalising on the number of platforms they now have at regional and extra-regional levels to further its case for international recognition—one of the two most frustrating factors for the Taliban regime in the 1990s, the other being lack of sustained international aid and assistance. Visits of the Taliban officials to regional capitals and visits of foreign officials to Kabul and the optics associated with both, not only helps the Taliban to project its regime as ‘new’, ‘different’ and ‘worth engaging’ but also sends a message to its commanders and fighters on the ground, as well as to the common people, that the regime in its current form is being increasingly engaged and accepted by the outside world, particularly by the regional countries, thus helping to secure legitimacy and recognition.55 Similarly, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan’s decision to delist the Taliban from their respective lists of banned organisations and Russia’s decision to follow suit in future have been projected by the Taliban as a testament to its growing acceptance in the region, and also its diplomatic ability to navigate the complex regional environment.56

On the issue of inclusivity, selling the idea of sharing power with members of the former regime, or having a diverse mix of coopted elements in their political structures, to the uncompromising ideological core and to an extent the rank and file, will be difficult—especially now that they have the entire country under their control. It could further deepen the resource competition/power struggle among various Taliban groups. Moreover, the Taliban as a Sunni Pashtun Islamist movement was never oriented to be a nationally unifying ideology, transcending ethnic, sectarian and linguistic identities. The political idea of a strictly Sharia-based rule simply never had the kind of mass appeal among the people that is required to unify the Afghan nation. At the same time, it is difficult for any ethnocentric over-centralised authoritarian structure to effectively control or contain the several complex social–political dynamics that play out at sub-national levels, often with support from across the border.

The Taliban’s notion of power and authority remains strongly militaristic and territorial, rather than political in nature. Buoyed by the complete decimation of the domestic political opposition and a sense of historic victory over a much powerful and collective Western alliance, the Taliban does not seem to be in need of co-opting ‘others’, particularly political elements long identified with factional or coalition politics and mobilisation of ethnic militias. The Taliban had first arisen in 1994 in rural Kandahar as a local rebellion against warring ‘mujahideen’ commanders in the south. The Taliban viewed the factionalised politics of the ‘mujahideen’ coalition—a mélange of Pakistan-backed ethnic ‘mujahideen’ groups that constantly fought among themselves and plunged the country into a brutal civil war—as a source of instability in the country.

The Taliban leadership has been averse to building coalitions and sharing power with opposition ethnic parties and militias or coopting them in its power structures. Their notion about inclusivity is mostly limited to extending amnesty to select figures from the previous regime, or retaining personnel in its administrative structures at mid and low levels, and working towards bringing technocrats, professionals and investors back to the country. The Taliban’s economic approach is more open and inclusive, when compared to its austere social and political approach. However, as women have been systematically kept out of the formal economic sectors, the future prospect of the few remaining women entrepreneurs in the light of the recently enacted New Vice and Virtue Law could be uncertain.

At the same time, in view of the power struggle and the element of distrust among key constituent groups, the Taliban would prefer to maintain the delicate internal equilibrium and the overall ideological–political cohesion within the ‘emirate’. The Taliban leaders believe that the international community has no option but to deal with them as they are in control of all Afghan territories, and subsequently recognise their ‘emirate’ as well, irrespective of its current form and policies. In August 2024, Acting Taliban Minister for Industry and Commerce Nooruddin Azizi claimed that Afghanistan is conducting trade with over 80 countries.57 While not a single country has officially recognised the Taliban regime, Acting Taliban Foreign Minister Muttaqi claimed in September that his ministry is in control of 39 Afghan embassies and consulates and have appointed diplomats to about 11 countries in the past year.58 This included Afghan missions run by diplomats appointed by the previous regime and which are now coordinating with the Taliban-run Afghan foreign ministry. China has become the first country to accredit a Taliban-appointed ambassador. The UAE and Uzbekistan too have accepted the Taliban-appointed ambassadors. The Acting Deputy Prime Minister for Political Affairs Abdul Kabir reportedly stated in early March 2024 that, “We say to the world that they have no option but to engage with the Islamic Emirate, because there is no one to engage with as a representative of Afghanistan”.59 There is also a view among the Taliban hardliners that the ‘emirate’ can do without any formal recognition from the international community.

The top Taliban ideologues based in Kandahar remain almost as insular as they were during their two decades of exile. The Taliban are still in the early years of their rule, confident of control over territories and borders of the country, and will likely remain averse to ideas of decentralisation or diversification of their political structures. Ideology also weighs heavily on the Taliban’s political approach to external interactions, narrowing the scope and space for diplomatic manoeuvring to strengthen the case for international recognition. With time, the ideological overlay on the Taliban’s policy approaches in both domestic and external domain could prove to be a liability for the regime. Akhundzada and his old cohorts have never been known for their diplomatic skills. External diplomacy and its nuances generally hold limited value in their chauvinist world.

On the security front, the return of the Deobandi Taliban to power had spurred a weakened neo-Salafi ISK into action. Although numerically much smaller and with a shrunken base, it still remains a key armed opposition group, predominantly Pashtun and Sunni Islamist like the Taliban, and a potential platform for disaffected Islamists and non-Taliban elements to challenge the Taliban regime. The ISK has its cross-border support networks. At the intra-Islamist level, the conflict between militant Deobandis and Salafis, which manifested in the 1990s following the Soviet withdrawal and rise of the Deobandi–Hanafi Taliban, exacerbated with the establishment of Islamic State’s Khorasan Wilayah or ‘Islamic State Khorasan Province’ in early 2015 and later with the return of the Taliban to power in August 2021.

Pro-ISK sentiments among sections of the Afghan Taliban are not ruled out. The Taliban might be at loggerheads with ISK, but the same cannot be said for its two key allies, the Haqqani Network and the Pakistani Taliban. The fact that all four Islamist groups—Afghan Taliban, Haqqani Network, ISK, and the Pakistani Taliban—are predominantly Sunni Pashtun, broader intra-Pashtun and intra-Islamist dynamics together seem to be at play in the entire Pashtun geography, with strong cross-border dimensions.

Unlike the Afghan Taliban, which so far has largely limited itself to Afghanistan and has had territorial stakes, the ISK has a transnational agenda and is open to collaborating with a range of non-state actors across South and Central Asia. A stronger ISK could further complicate the security scenario in the region, particularly as both al-Qaeda and ISK compete to expand their influence and control over regional militant groups/networks.

The al-Qaeda had been pledging its loyalty to successive Taliban chiefs, beginning with Mullah Omar in the 1990s, Akhtar Mohammad Mansur in August 2015 to the current Taliban chief Akhundzada in May 2016. It had reiterated its loyalty to the Taliban chief at the time of ISIS announcing the establishment of its Caliphate in June 2014. Today, one finds only Pashtun Islamist groups collaborating, competing and warring to establish their power dominance and ideological hold in Afghanistan, and by extension the Pashtun territories in northwest Pakistan. The Haqqani Network, which is perhaps the most dynamic of all groups within the ‘emirate’ and is known for its skills at power brokerage and political mediation, has the potential to tilt the power balance. Sirajuddin Haqqani is charting his own course both within the ‘emirate’ and on the external front. His network among eastern Pashtun tribes, particularly in the Loya Paktia region, the traditional Haqqani stronghold, has only grown with time. The unfolding intra-Pashtun dynamic is bound to have consequences for both the Afghan Taliban and the region, mostly still unforeseen, as old and cold strategic calculations continue to steer geopolitics in and around Afghanistan.

The Taliban has consciously avoided entangling itself with inter-state and regional conflicts. The Taliban leaders and representatives have long been assuaging the security concerns among the regional countries, as they sought transactional ties based on non-interference in internal affairs on a reciprocal basis.60 That, however, likely depends on the stability and survivability of the Taliban regime, and its capacity to govern Afghanistan. The Taliban may have called off jihad but not its Islamist allies. Unless the Taliban adopts relatively non-intrusive social policies and embraces people-centric approaches to governance, it will remain somewhat a mirror image of its old regressive self from the 1990s. In the long-term, should ideological rigidities prove a liability to the regime, certain interest groups within may re-align and morph into polarised entities. In the longer run, it could open an altogether new or a rather familiar chapter of alliance politics and resource competition in the decades old Afghan continuum.

The Taliban and its ‘emirate’ appear to be in a state of transition, at least generationally if not organisationally. As the regime consolidates itself, questions are being raised from within, particularly as Kandahar seeks to maintain status quo on contentious issues and moves to assert greater control over the political leadership in Kabul, sections of which have instead sought change in regime’s behaviour and policy approaches, in consonance with the practicalities of conduct of State and international affairs.

The internal powerplay that unfolded early on in the run-up to the formation of the interim cabinet in September 2021, followed by serious policy differences that emerged on the issue of reopening of secondary schools for girls in March 2022, not only exposed the old rifts within the ‘emirate’ but also served as a pretext for the Kandahar clique to increasingly exert its authority over all affairs of the ‘emirate’. It also strengthened the case for maintaining the overall policy status quo on contentious issues. The Taliban have lived with, and also survived, internal disagreements and schisms over the past three decades, and have successfully maintained a façade of unity, but with a new generation of Taliban leaders and commanders asserting their vision of the ‘emirate’, it may be challenging for the Taliban chief Akhundzada to effectively sustain his institutional authority in the long run. Meanwhile, prioritising regime stability and consolidation over everything else, including the issue of international recognition, the Taliban in the third year of their rule largely remain their fundamental self, marginalising in the process the much larger and diverse Afghanistan, which perhaps is now the ‘other Afghanistan’. To offset the persistent criticism of the regime for lacking social and political inclusivity and imposing severe social restrictions on girls and women, the Kabul-based Taliban leaders have also increased their public outreach and come up with counter narratives.

Since the Taliban are now fully based inside Afghanistan, in control of all its territories, and seek to legitimate their regime, they have no option but to make a transition from aggressive ideological mongering and warfighting to responsive and representative governance, from a potentially destabilising to a stabilising force, and from a blacklisted to a delisted, relatable State actor. However, the Taliban rule will run its course, so long as it is not caught in the broader intra-Pashtun power dynamic and on the wrong side of the regional geopolitics. Until then, the Taliban and its ‘emirate’ will maintain a façade of unity.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. The ‘Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan’ is not recognised at the United Nations (UN), or by any member state of the UN, as of 31 October 2024. Afghanistan is still represented at the UN Headquarters in New York and its offices in Geneva and Vienna by diplomats appointed by the previous Afghan Government. Naseer Ahmed Faiq, Chargé d’affaires, a.i, represents Afghanistan’s permanent mission to the UN in New York. See “List of Permanent Representatives and Observers to the United Nations in New York (As of Monday, 7 October 2024)”, UN Protocol and Liaison Service, New York, 2024, p. 1. Faiq was appointed as minister counsellor in the Afghan permanent mission in September 2019 and assumed the current position in December 2021. See Afghanistan Mission, “The Permanent Mission of the I.R of Afghanistan to the United Nations in New York would like to inform that…”, X (formerly Twitter), 17 December 2021, 7:09 AM. Amb Nasir Ahmad Andisha represents Afghanistan’s permanent mission to the UN Office in Geneva. See “Missions Permanentes Auprès Des Nations Unies À Genève Nº 122 (Updated on 28 October 2024)”, The Blue Book of Permanent Missions, Geneva, Edition No. 122, 2024, p. 11. Amb Andisha had presented his credentials on 1 April 2019. See “New Permanent Representative of Afghanistan Presents Credentials to the Director-General of the United Nations Office at Geneva”, UN Office at Geneva, 1 April 2019. Similarly, Amb Manizha Bakhtari represents Afghanistan’s permanent mission to the UN Office in Vienna. See The UNOV Blue Book – Member States, UN Office at Vienna, Protocol Service, Vienna, last updated on 16 September 2024. Amb Bakhtari had presented her credentials on 15 March 2021. See “Permanent Representative of Afghanistan Presents Credentials”, The UN Information Service, Vienna, 15 March 2021.

- 2. Hamid Karzai, Former President of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, “Following the departure of Mr. Ashraf Ghani and the responsible officials from the country…”, X (formerly Twitter), 15 August 2021, 8:34 PM; Abdullah Abdullah, Former Chairman of the High Council for National Reconciliation, “HE Dr Abdullah Abdullah, Chairman of HCNR @SapedarPalace, yesterday evening at his residence met…”, X (formerly Twitter), 19 August 2021, 1:08 PM; “Along with HE @KarzaiH, we welcomed members of the Taliban political office, & negotiation team...”, X (formerly Twitter), 21 August 2021 10:29 PM; “Taliban Members Meet Political Leaders in Kabul”, Tolo News, 18 August 2021; “Taliban's Anas Haqqani Meets Afghan Leaders Hamid Karzai, Abdullah Abdullah”, Geo News, 18 August 2021; “Taliban Delegation Meets Karzai Amid Efforts to Form New Afghan Govt.”, The Express Tribune, 19 August 2021; “Karzai, Abdullah Meet Taliban Political Office Members in Kabul”, Tolo News, 22 August 2021; Susannah George, “In Quest for Legitimacy and to Keep Money Flowing, Taliban Pushes for Political Deal with Rivals”, The Washington Post, 25 August 2021.

- 3. “Fourteenth Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2665 (2022) Concerning the Taliban and Other Associated Individuals and Entities Constituting a Threat to the Peace Stability and Security of Afghanistan”, United Nations Security Council, S/2023/370, 1 June 2023, p. 3.

- 4. Ibid., p. 5.

- 5. “Fifteenth Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2716 (2023) Concerning the Taliban and Other Associated Individuals and Entities Constituting a Threat to the Peace, Stability and Security of Afghanistan”, United Nations Security Council, S/2024/499, 8 July 2024, p. 7.

- 6. “The Ambar al-Moruf and Nahi al-Munkar Law Came into Force and Was Published in the Official Gazette”, Radio Television of Afghanistan, 22 August 2024; Amin Kawa, “Taliban’s Law for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice: Citizens Face Collective Humiliation and Dehumanization”, Hasht-e-Subh, 24 August 2024.

- 7. Hassan Abbas, Distinguished Professor at National Defence University, Washington, DC, in his book published in 2023 had listed 18 Taliban graduates of Darul Uloom Haqqania holding senior positions in the caretaker/interim Taliban government. The list included two deputy prime ministers, the chief justice, seven cabinet ministers, four deputy ministers, two provincial governors, the deputy governor of Afghan Central Bank, and the Head of the passport department. For details, see Appendix II in Hassan Abbas, The Return of the Taliban: Afghanistan After the Americans Left, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2023, pp. 258–259.

- 8. “Statement of Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan Regarding Cabinet Announcement”, Al Emarah, 7 September 2021.

- 9. Former Guantanamo Bay detainees in the caretaker/interim cabinet announced on 7 September 2021 included Acting Minister of Information and Culture Khairullah Khairkhwa, Acting Minister of Border and Tribal Affairs Noorullah Noori, Deputy Minister of Defence Mohammad Fazil ‘Mazloom’, and Acting Director-General of the Taliban Intelligence Abdul Haq Wasiq. In the first Taliban regime (1996–2001), Khairkhwa, a co-founder of the Taliban group, was the governor of Herat Province; Noori was in-charge of the northern region and the governor of Balkh Province; Fazil was the chief/deputy chief of staff of the Taliban forces; and Wasiq was even then the deputy head of the Taliban intelligence. All four after their release from the US custody in early 2014 were later inducted as part of the Taliban negotiating team based in Doha.

- 10. Rajab Taieb, “New Cabinet Members Announced, Inauguration Cancelled”, Tolo News, 21 September 2021.

- 11. “Islamic Emirate Leader Appoints New Acting Minister of Public Health”, Tolo News, 28 May 2024.

- 12. “Fourteenth Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2665 (2022) Concerning the Taliban and Other Associated Individuals and Entities Constituting a Threat to the Peace Stability and Security of Afghanistan”, no. 3, p. 6.

- 13. Khudai Noor Nasar, “Afghanistan: Taliban Leaders in Bust-up at Presidential Palace, Sources Say”, BBC Islamabad, 15 September 2021; Eltaf Najafizada, “Taliban Shootout in Palace Sidelines Leader Who Dealt With U.S.”, Bloomberg News, 17 September 2021.

- 14. “Taliban Section Claims Mansour Injured in Internal Firefight”, Dawn, 3 December 2015; Tahir Khan, “Taliban Leader Mullah Akhtar Mansour Injured in Firefight: Officials”, The Express Tribune, 2 December 2015; “Mullah Mansoor Reportedly Shot Injured in Quetta Firefight”, Pajhwok Afghan News, 3 December 2015.