You are here

US and EU Sanctions on Russian Defence Industry

Summary: The US and EU sanctions have targeted key Russian arms producing firms, their design bureaus, export organisations and their leadership, as well as the export and import of dual-use products. Given that India is one of the largest importers of Russian arms, it has been impacted by such sanctions. While suggestions to overcome these complications in the near and medium-terms have included the possible creation of escrow accounts and delayed payments, for the longer term, there is no denying the fact that the country’s ‘Aatmanirbhar’ drive for achieving defence self-reliance will have to be further strengthened.

Summary: The US and EU sanctions have targeted key Russian arms producing firms, their design bureaus, export organisations and their leadership, as well as the export and import of dual-use products. Given that India is one of the largest importers of Russian arms, it has been impacted by such sanctions. While suggestions to overcome these complications in the near and medium-terms have included the possible creation of escrow accounts and delayed payments, for the longer term, there is no denying the fact that the country’s ‘Aatmanirbhar’ drive for achieving defence self-reliance will have to be further strengthened.

The Russian Federation is one of the major global arms exporters. The top five importers of Russian arms during 2010–21 were India, China, Algeria, Vietnam and Egypt. Russia’s share of global arms trade, however, has gradually decreased from 26 per cent in 2011–15 to 19 per cent in 2017–21.1 In the last five years (2017–21), while Russian arms made up more than 80 per cent of China’s and Algeria’s arms imports, they accounted for 56 per cent of Vietnam’s, 46 per cent of India’s and 41 per cent of Egypt’s arms imports.

Due to Russia’s military actions in Ukraine, since 2014, Russia has been subjected to sanctions measures by the United States (US), European Union (EU) and other countries. In the wake of its February 2022 military action in Ukraine, these sanctions have been further strengthened. The sanctions have targeted key Russian arms producing firms, their design bureaus, export organisations and their leadership, as well as the export and import of dual-use products. This Issue Brief examines the different US and EU sanctions on the Russian defence industry, and the implications they have had for Russian arms importing countries, like Turkey and Indonesia. Given that India is one of the largest importers of Russian arms, it has been impacted by such sanctions.

EU Sanctions

As part of EU sanctions, more than a thousand individuals and nearly 100 entities are subject to travel bans and asset freezes. Six ‘packages’ of sanctions have been imposed beginning from 23 February till 3 June, with sanctions targeting 70 per cent of Russia’s banking system (as per the EU’s contention), closed EU airspace and ports to Russian aircraft and vessels and imposed import and export restrictions on items like Russian steel (with effect from August 2022), coal, crude oil, among others.2 As regards defence and dual-use sectors, business transactions with key companies in the aviation, shipbuilding and machine-building sectors are threatened to be sanctioned, while export restrictions on dual-use goods and technology that could ‘contribute to the technological advancement of Russia’s defence and security sector’ were tightened.3

While the prohibition on dual-use goods has been in place for military end-users, it was extended to civilian end-users too from February 2022. Analysts note that restrictions on sourcing critical components like semi-conductors, machining equipment, among others, will negatively impact the ability of Russia’s defence industrial enterprise. Micro-electronics and high-end machining equipment were described as the ‘achilles heel’ of the Russian defence industry, way back in 2015, by Deputy Prime Minister Dmitri Rogozin.4

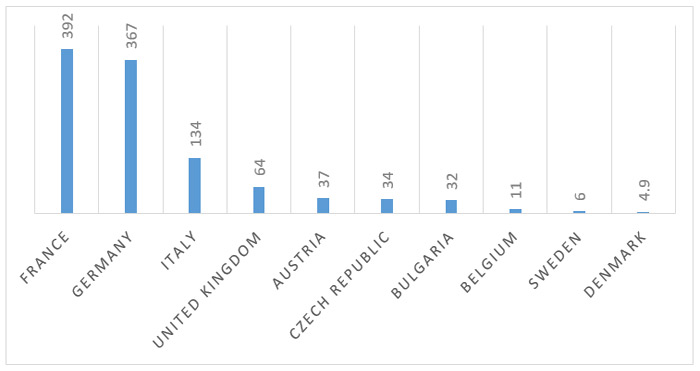

Prior to the latest round of sanctions, the EU arms export and import ban has been in place since July 2014. The EU, in Council Decision 2014/512/CFSP, banned the export and import of arms, including sale, supply or transfer of weapons, ammunition, military vehicles, or technical and financial assistance for military activities.5 More than EUR 900 million of defence trade took place between EU states and Russia, however, in the period 2010–20, with significant portion of it contributed by countries like France, Germany and Italy.6

Reports note that German engine parts and global positioning systems (GPS) have been found in Russian drones shot down in Ukraine. Italy has exported military trucks and semi-automatic weapons and ammunition, while infra-red systems for fighter jets and thermal imaging equipment for tanks, among other equipment, have been exported by France.7 Russian arms have also been exported to EU member states—to Cyprus, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia, in the past decade, though the majority of these exports have happened prior to 2012.

To be sure, the 2014 ban did not prohibit servicing of spares, among others, for contracts entered into prior to August 2014. EU sanctions measures are also not applicable for equipment meant for civilian nuclear use, or for transactions involving companies jointly or solely owned by EU entities. There has been a reduction, though, in arms export licenses from EU states to Russia, reducing from 940 in 2013 to 86 in 2020 (see Tables 1 and 2).8 EU states insist, therefore, that they have been strictly following the sanctions measures. The EU, in April 2022, also removed this exemption relating to servicing of arms equipment brought prior to August 2014.9

Source: European Network against Arms Trade.

Source: European Network against Arms Trade.

US Sanctions

The Obama administration passed Executive Order (EO) 13661 and EO 13662 in March 2014 blocking the ‘property or interests in property of persons operating in the arms and related material sectors of the Russian Federation’.10 These two authorities were later codified by the Countering American Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA).

In July 2014, the US Treasury designated and blocked the assets of Russian military enterprises like Almaz-Antey, Federal State Unitary Enterprise State Research and Production Enterprise Bazalt, JSC Concern Sozvezdie, JSC MIC NPO Mashinostroyenia, Kalashnikov Concern, KBP Instrument Design Bureau, Radio-Electronic Technologies, and Uralvagonzavod, under EO 13661.11

The Ukraine Freedom Support of December 2014 imposed sanctions on the Russian arms export organisation, Rosoboronexport and threatened sanctions on ‘any person for knowingly facilitating a significant financial transaction with any Russian producers, transferors or brokers of defence articles’. The Act had an in-built waiver for not imposing these sanctions for national security reasons.12

CAATSA, meanwhile, was passed in 2017 as a measure to punish Iran, Russia and North Korea for their alleged malicious activities. Russian ‘malafide’ actions that were flagged included its invasion of Georgia (2008), Ukraine (2014) and Crimea (2014) and its alleged involvement in the 2016 US Presidential elections. Section 231 of CAATSA prescribed ‘sanctions for engaging in “significant” transactions with defence and intelligence sectors of Russia’.13

These sanctions included restrictions on accessing US EXIM Bank loans, denial of export sanctions, prohibition of loans from US financial institutions totaling more than US$ 10 million, opposing loans from international financial institutions, and sanctions on principal executive officers of entities who indulge in such ‘significant transactions’. In September 2017, the US President delegated the authority to implement Section 231 to the US Secretary of State, in consultation with US Treasury Secretary.

Turkey has been at the receiving end of US sanctions pressure on account of its US$ 2.5 billion purchase of the S-400 system, announced in December 2017. Negotiations for the system had commenced in June 2016, after the deal for a similar Chinese system was cancelled in November 2015, over contentions regarding transfer of technology (ToT) issues.14 The Chinese system was chosen in September 2013. After the Chinese deal was cancelled, negotiations were also held with US companies like Raytheon and Lockheed Martin—makers of the Patriot system—but disagreement over ToT stymied the deal.

Turkey began constructing S-400 base in September 2018. The US removed Turkey from the F-35 programme in June 2019. Turkey was to get nearly 100 F-35 jets and Turkish companies were making F-35 centre fuselages and cockpit displays. Reports noted that approximately 7 per cent of the jet’s parts were being made in Turkey.15

While the F-35 removal was not prescribed under CAATSA sanctions, the US took the decision after Turkey sent personnel to Russia for training on the S-400 system. The US insisted that the S-400 procurement would lead to Turkish strategic and economic overdependence on Russia. The White House asserted that the F-35 cannot co-exist with a Russian intelligence collection programme (S-400) and that its acquisition undermines the commitments of NATO allies to move away from Russian systems.16 In December 2020, Section 231 CAATSA sanctions were finally imposed on Turkey’s arms procurement agency (SSB), including asset freezes and visa restrictions on its president and other officers.

As for recent developments on Turkey–US defence ties, the US State Department, in letter to Congress on Turkey’s request for F-16 fighters, stated that ‘compelling long-term NATO alliance unity and capability interests, as well as US national security, economic and commercial interests are supported by appropriate US defense trade ties with Turkey’ and noted that Turkey had already paid a ‘significant price’ on account of its removal from the F-35 programme and the CAATSA sanctions.17

Apart from Turkey, other countries that have been sanctioned by the US over their arms relationship with Russia include China. CAATSA sanctions were imposed on the Chinese arms procurement agency, EDD, and its director, in September 2018. The Chinese purchase of the Su-35 fighter jet in 2017 and the S-400 system in 2018 were deemed as ‘significant’ transactions with the Russian defence industry.18 Indonesia in December 2021 also backed out of deals to buy 11 Su-35 jets for more than US$ 1 billion.19 Reports in 2019 had noted that Morocco was reconsidering an option to buy the S-400, in view of the threat of US sanctions. In January 2021, the US approved the sale of the Patriot air defence system to Morocco.20

Consequences for India

US and EU sanctions measures have added pressure to India’s strategic options. India is one of the largest importers of Russian arms, accounting for nearly 34 per cent of Russia’s exports, during 2010–21, followed by China, at 13.5 per cent.21 The head of Rostec, the Russian arms conglomerate, in August 2021 stated that the cumulative value of defence deals between India and Russia since 2018 was US$ 15 billion.22 The Russian arms deals signed during the period 2018–22 are mentioned in Table 3.

2018 |

S-400 Triumf SAM system (5 units) (Being inducted) |

|

Talwar class frigates (4) |

|

|

Type 877 submarines (upgrades) |

|

|

2019 |

Konkurs anti-tank missile |

|

Project 9711 Nuclear submarine |

|

|

R-73 and R-77 BVRAAM |

|

|

Igla-S portable SAM |

|

|

KA-31 AEW helicopter (negotiations suspended in 2022) |

|

|

T-90S MBT |

|

|

2021 |

Su-30 MKI FGA (Upgrades; put on hold) |

|

AK-203 assault rifles (Being inducted) |

|

|

2022 |

Konkurs anti-tank missile |

Source: SIPRI Arms Trade Registers; Media reports.

Reports in May 2022 flagged that India has halted negotiations for 10 additional Ka-31 early warning helicopters—to the 14 it has in its inventory, due to uncertainties arising on account of US sanctions measures.23 The Indian Air Force’s (IAF) plan to upgrade its frontline Su-30 MKI fighter jets has also reportedly been put on hold.24 US sanctions pressure was also cited as one of the reasons for lack of progress in finalising the deal for the Ka-226T light utility helicopters, powered by French engines.25

Earlier in March 2022, US Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs, Donald Lu, while responding to a question from Democratic Senator Chris Van Hollen whether India’s abstentions at the United Nations on Ukraine-related resolutions will impact the administration’s decisions on a possible CAATSA waiver going forward, stated that India has cancelled orders for Mig-29 fighter jets, anti-tank weapons, and helicopters ‘in just the last few weeks’.26 There has been no formal confirmation, though, from Indian officials, of these cancellations.

As for the S-400, India entered into the US$ 5.4 billion deal with the Russian Federation in October 2018 for five units of the system. The first unit was deployed in December 2021 while the deliveries for the second unit began in April 2022. Even as US officials have been maintaining that India should reduce its dependence on Russian equipment, as on date, the US Secretary of State, in consultation with the US Treasury Secretary, has not made the determination for the US President that India’s purchases of the S-400 constitute a ‘significant’ transaction with the Russian defence sector.

US legislative support for granting India such a waiver, though, is strong. Republican Senators and Congressmen, led by Senator Ted Cruz, introduced the Circumspectly Reducing Unintended Consequences Impairing Alliances and Leadership Act of 2021 (CRUCIAL) legislation in both the Senate (October 2021) and the House of Representatives (November 2021), urging the US President not to impose CAATSA sanctions for a 10-year period, if he certifies to the US Congress that India is cooperating with the US on ‘security matters that are critical to United States strategic interests’ in the Indo-Pacific.27 Republican lawmakers, though, have been critical of India’s voting stance at the UN on Ukraine. At the Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing in March 2022, Senator Cruz enquired from Assistant Secretary Lu if India’s votes reduced the incentives for the US to continue to consider the CAATSA sanctions waiver.28

The US House of Representatives, meanwhile, on 14 July 2022, overwhelmingly passed an amendment to the National Defense Authorisation Act (NDAA), introduced by Congressman Ro Khanna, urging the Biden administration to provide India with a CAATSA waiver ‘to support India’s immediate defense needs’ in the face of ‘serious border threats from China’. The amendment also urges the US to take additional steps to ‘accelerate India’s transition off Russian-built weapons and defense systems’.29

The amendment was passed with 330 members voting in favour (214 Democrats and 116 Republicans) and 99 against (5 Democrats and 94 Republicans).30 Representative Khanna, a Democrat from California, affirmed that the amendment was the most significant bipartisan legislative action pertaining to India–US relations, since the 2005 nuclear deal.31 While the US President will still have to provide the waiver, the amendment is an important indication of strong bipartisan support that acknowledges India’s need to ‘maintain its heavily Russian-built weapons systems’.32

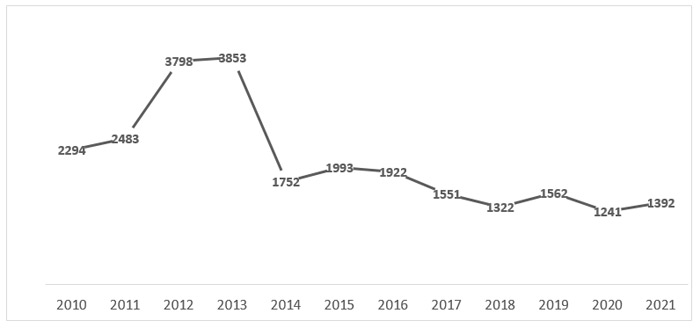

Analysts have also flagged possible issues that Indian and Russian defence joint venture companies could face in fulfilling export orders or in bagging new orders.33 India entered into a US$ 375 million contract with Philippines in January 2022, for the supply of the Brahmos missile system. The Office of Foreign Assets and Control’s (OFAC’s) ‘50 per cent rule’, states that sanctions will be imposed on ‘any entity owned in the aggregate, directly or indirectly, 50 percent or more by one or more blocked persons’.34 Brahmos JV is not owned 50 per cent or more owned by the Russian JV partner, NPO Mashinostroyenia (which is under US sanctions since 2014). Recent reports have also noted that Indonesia was in advanced talks with India to procure the Brahmos missile.35 The trend indicator values (TIV) of Russia’s arms exports to India during the period 2010–21 are mentioned in Figure 1.

Source: SIPRI Arms Transfers Database

Note: SIPRI Trend Indicator Values (TIV) do not represent the actual financial value of arms transfers.

Conclusion

US and EU sanctions have had implications for countries that import major Russian defence equipment. Turkey, India and China are pertinent examples in this regard. India could not conclude key arms procurement contracts like those for light utility helicopters, on account of US sanctions pressure, among other issues. Reports have highlighted how it could face issues with regard to paying for contracted weapons systems, for instance. Major purchases like the S-400 system have been under the sanctions cloud, though legislative support in favour of the US administration providing sanctions waiver has gathered momentum. While suggestions to overcome these complications in the near and medium-terms have included the possible creation of escrow accounts and delayed payments, for the longer term, there is no denying the fact that the country’s ‘Aatmanirbhar’ drive for achieving defence self-reliance will have to be further strengthened.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. Pieter D. Wezeman, Alexandra Kuimova and Siemon T. Wezeman, “Trends in International Arms Transfers 2021”, SIPRI Fact Sheet, March 2022; Pieter D. Wezeman, Alexandra Kuimova and Siemon T. Wezeman, "Trends in International Arms Transfers 2020”, SIPRI Fact Sheet, March 2021.

- 2. “Sanctions Adopted Following Russia’s Military Aggression against Ukraine”, European Commission.

- 3. “Council Decision 2022/430 of 15 March 2022 amending Decision 2014/512/CFSP Concerning Restrictive Measures in view of Russia’s Actions Destabilising the Situation in Ukraine”, Official Journal of the European Union, Vol. 65, 15 March 2022. Countries like Japan, Taiwan and South Korea have also imposed restrictions on exports to Russia of critical components like semi-conductors, among others. Sebastian Moss, “Intel and AMD Halt Chip Sales to Russia, TSMC Joins In on Sanctions”, DCD, 28 February 2022; Lara Williams, “Taiwan’s Semiconductor Ban Could Spell Catastrophe for Russia”, Investment Monitor, 3 March 2022; “In Rare Stand, South Korea, Singapore Unveil Sanctions on Russia”, Al Jazeera, 28 February 2022.

- 4. Cited in Richard Connolly and Mathieu Boulègue, “Russia’s New State Armament Programme: Implications for the Russian Armed Forces and Military Capabilities to 2027”, Chatham House, May 2018, p. 30.

- 5. “Council Decision 2014/512/CFSP of 31 July 2014 Concerning Restrictive Measures in view of Russia's Actions Destabilising the Situation in Ukraine”, Official Journal of the European Union, 31 July 2014.

- 6. EU Export Data Browser, European Network against Arms Trade.

- 7. Laure Brillaud, Ana Curic, Maria Maggiore, Leïla Miñano and Nico Schmidt, “EU Member States Exported Weapons to Russia after the 2014 Embargo”, Investigate Europe, 17 March 2022.

- 8. “Council Working Group on Conventional Arms Exports”, European External Action Service.

- 9. Francesco Guarascio, “EU Closes Loophole Allowing Multimillion-euro Arms Sales to Russia”, Reuters, 14 April 2022; “Answer Given by High Representative/Vice-President Borrell i Fontelles on behalf of the European Commission”, European Parliament, 7 June 2022.

- 10. “Blocking Property of Additional Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine”, Executive Order 13661 of March 16, 2014, Federal Register, Vol. 79, No. 53, 19 March 2014; “Blocking Property of Additional Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine”, Executive Order 13662 of March 20, 2014, Federal Register, Vol. 79, No. 56, 24 March 2014.

- 11. “Announcement of Treasury Sanctions on Entities Within the Financial Services and Energy Sectors of Russia, Against Arms or Related Materiel Entities, and those Undermining Ukraine's Sovereignty”, US Department of the Treasury, 16 July 2014.

- 12. “The Ukraine Freedom Support Act 2014”, US Congress, 18 December 2014.

- 13. “Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act 2017”, US Congress, 2 August 2017.

- 14. Ali Ünal, “Turkey Cancels $3.4B Missile Deal with China to Launch Own Project”, Daily Sabah, 15 November 2015.

- 15. “U.S. Congressional Committee Leaders Warn Turkey on F-35, S-400”, Reuters, 9 April 2019.

- 16. “White House Says Turkey's Involvement in F-35 Program ‘Impossible’”, Reuters, 17 July 2019.

- 17. Humeyra Pamuk, “U.S. Says Potential F-16 Sale to Turkey would Serve U.S. Interests, NATO: Letter”, Reuters, 8 April 2022.

- 18. “Sanctions under Section 231 of the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act of 2017 (CAATSA)”, US Department of State, 20 September 2018.

- 19. Alessandra Giovanzanti, “Indonesia Excludes Su-35 from Fighter Aircraft Acquisition Plans”, Janes, 23 December 2021.

- 20. “US Confirms Sale of PATRIOT Missiles to Morocco”, The North Africa Post, 21 January 2021.

- 21. “Importer-Exporter TIV Tables”, SIPRI.

- 22. Dinakar Peri, “India-Russia Defence Trade Worth $15 Billion in Three Years: Russian Official”, The Hindu, 24 August 2021.

- 23. Vivek Raghuvanshi, “India Halts Ka-31 Deal with Russia”, Defense News, 16 May 2022.

- 24. “Amid Ukraine-Russia War, IAF's Rs 35,000 cr Plan to Upgrade Su-30 Fighter Fleet Put On Backburner”, ANI, 8 May 2022.

- 25. Rahul Bedi, “India’s Protracted Saga to Acquire Russian Choppers Unlikely to Materialise in Entirety”, The Wire, 29 December 2021.

- 26. See “U.S. Policy Towards India”, Subcommittee on Near East, South East, Central Asia and Counterterrorism, United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, 2 March 2022.

- 27. “CRUCIAL Act of 2021”, US Congress, 28 October 2021; “H.R. 6033, CRUCIAL Act of 2021”, US Congress, 18 November 2021.

- 28. “U.S. Policy towards India”, no. 26.

- 29. “Release: House Passes Khanna’s Historic Amendment to Strengthen U.S. and India Defense Partnership”, Congressman RO Khanna, 14 July 2022.

- 30. “Final Vote Results for Roll Call 332”, 14 July 2022.

- 31. “India-Russia Deal: RO Khanna Lists Out Reasons Why US Waived Off CAATSA Sanctions Against New Delhi”, India Today, 20 July 2022.

- 32. “Release: House Passes Khanna’s Historic Amendment to Strengthen U.S. and India Defense Partnership”, no. 29.

- 33. Rahul Bedi, “India Ready to Sell BrahMos, but Exports Remain Hostage to Concerns Over CAATSA”, The Wire, 4 March 2021; Gurjit Singh, “BrahMos Export Opens Up Strategic Arena”, The Tribune, 8 February 2022.

- 34. "Entities Owned by Blocked Persons (50% Rule)”, US Department of the Treasury, 13 August 2014.

- 35. Huma Siddiqui, “FE Exclusive: Indonesia to Buy BrahMos Missile from India? Talks in Advance Stage”, The Financial Express, 19 July 2022.