You are here

ADMM-Plus and India’s Act East Policy

Summary

Forums like the ADMM-Plus have played a crucial role in enhancing strategic depth between India and ASEAN. In a very short time, the ADMM-Plus has evolved into a promising and inclusive forum for dealing with the hard-security issues of the Indo-Pacific. The geographic contiguity of its members, the security orientation of its leadership and its task-specific Expert Working Groups (EWG) increase ADMM-Plus’s potential to deliver tangible outcomes beyond the rhetoric of joint statements. The ADMM-Plus offers India and ASEAN opportunities to develop practical collaboration on security issues ranging from terrorism, maritime threats and other non-traditional threats.

On 23 November 2022, the 9th ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus) was held in Siem Reap, Cambodia. Raksha Mantri (RM) Rajnath Singh attended the meeting. The timing of the meeting was significant for India–ASEAN relations as it came just 11 days after the conclusion of the 19th ASEAN–India Summit in Cambodia, where India–ASEAN Strategic Partnership was elevated to a Comprehensive Strategic partnership.1

The ADMM-Plus brings together the ten ASEAN nations along with its eight dialogue partners that include India, China, Russia, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and the US to collaborate on hard security issues. It is an important forum that promotes ‘ASEAN centrality’ and ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’—both of which are an essential part of India’s strategic interests in the region. The Brief firstly analyses the factors that led to the creation of ADMM-Plus and makes assessments of its various strengths and limitations. Second, the significance of ADMM-Plus to India’s Act East policy will be evaluated.

Factors that Necessitated the Creation of ADMM-Plus

The origins of ADMM-Plus is intricately embedded with the evolution of collective defence architecture and the security-oriented regionalism of ASEAN. After the establishment of ASEAN in 1967, its founding members were keen on building a peaceful and stable region, given the then-prevailing tensions of the Cold War characterised by Great power rivalry.2 As a result, fostering greater economic and socio-cultural cooperation with Southeast Asia was prioritised.

However, during the late 1970s and 1980s, imperatives for fostering defence cooperation within Southeast Asia was recognised. Such cooperation remained restricted to the bilateral level within ASEAN. Although the then Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, mooted the idea for the creation of a multilateral defence forum in the 1980s, it was not supported by the other ASEAN nations. The breakthrough came in July 1993 during the Twenty-Sixth ASEAN Ministerial Meeting held in Singapore, where consensus was reached for establishing the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF).

The ARF was envisaged as a platform for promoting consensus-based decision making and facilitating frank dialogue on political and security issues pertaining to the Asia-Pacific region. Confidence-building measures (CBMs) and preventive diplomacy (PD) mechanisms were identified as the tangible deliverables in the maiden Chairman’s statement of the forum, released in 1994. The ARF comprises 27 nations including the ten ASEAN nations, its eight dialogue partners, along with other nations like Bangladesh, Pakistan, North Korea, Mongolia, Sri Lanka, Papua New Guinea and Timor-Leste.3 In 1995, the ARF envisaged a three-stage roadmap for achieving its objectives. These included Promotion of CBMs (Stage I), Development of PD mechanisms (Stage II) and Development of Conflict-Resolution mechanisms (Stage III).4

By early 2000s however, progress was slow and the ARF was seemingly unable to move beyond the first stage of CBMs. Differences arose among the ARF members regarding establishment of concrete PD mechanisms. The US, the EU, Japan, Canada and Australia advocated for tangible PD mechanisms like the establishment of early warning systems (EWS), fact-finding missions and enhanced good-offices. On the other hand, nations like China, Myanmar and Vietnam showed apprehensions regarding these efforts as they perceived these PD mechanisms would compromise their sovereignty. Also, the Foreign Ministers-led ARF’s rigid governance structure that relied on the absolute consensus of all its members affected flexibility to make progress, due to disagreements on certain issues.5

These shortcomings were identified in the ASEAN’s 2004 Vientiane Action Programme (VAP). This document envisaged an exclusive outward-looking external relations strategy with ASEAN’s major dialogue partners for achieving tangible deliverables required for establishing PD and conflict resolution mechanisms in the Asia-Pacific region. The VAP initiated modalities for the establishment of ADMM and ADMM-Plus, to look beyond the ASEAN for experience, expertise and resources for dealing with the hard regional security challenges.6 This subsequently led to the establishment of both platforms in 2006 and 2010 respectively. According to Siew Mun Tang, the establishment of ADMM 12 years after the ARF reflects ASEAN’s cautious approach towards establishing security regimes in the region.7

Achievements and Strengths of ADMM-Plus

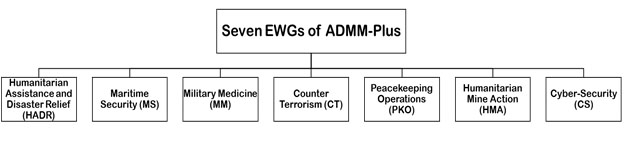

Since its establishment, the ADMM-Plus progressively evolved to become a promising forum that brought together the ten ASEAN states and its eight dialogue partners for achieving practical cooperation on hard security issues. Despite the underlying strategic competition and great power rivalry in the Indo-Pacific, the ADMM-Plus has achieved considerable success in forging practical security collaborations between the crucial stakeholders of the regions. The ADMM-Plus led by the Defence Ministers and senior military officials has been successful in creating task-specific Expert Working Groups (EWG). Each of these EWGs focus on a specific non-traditional security issue and is co-chaired by one ASEAN nation along with a dialogue partner for a cycle of three years.8 Currently the ADMM-Plus has seven EWGs as illustrated in Figure 1.

Source: “Chairman’s Statement on the Fourth ASEA Defence Ministers’ Meeting-Plus”, Manila, 24 October 2017.

Through these EWGs, the ADMM-Plus has been successful in orchestrating a range of activities like Table-Top Exercises (TTX) and Field Training Exercises (FTX) for achieving practical defence collaboration. Since 2013, the EWG on HADR has been successfully conducting regular joint training exercises for enhancing synergy in mounting large-scale disaster relief operations and establishing regional relief storage stations.

The Indo-Pacific being amongst the most disaster-prone regions of the world, HADR has been a vital area for cooperation among the ADMM-Plus nations. The EWG on MS has been conducting regular TTX and FTX for countering threats like piracy and smuggling. Through this EWG, the ADMM-Plus Maritime Security Community Information-Sharing Portal (AMSCIP) has been established to enhance the flow of information among the members.9

In light of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the EWG on MM has been particularly proactive in the management of pharmaceutical resources and creating innovation in healthcare.10 The ASEAN Centre for Military Medicine (ACMM) has been established in Bangkok and ASEAN Military Medical handbook has been drafted through this EWG.11 Major headways in the enhancement of collective CT capability has been achieved through the ADMM-Plus’s dedicated EWG on CT. This EWG has been instrumental in creating the ‘Our Eyes’ initiatives for the dissemination of strategic information on terrorism-related incidents and potential terror attacks.12

Taking into context these developments, many scholars and observers have opined that ADMM-Plus has been more successful than other ASEAN-centric platforms like the ARF and Shangri-La Dialogue (SLD). This success can be attributed to certain unique strengths of ADMM-Plus that enable it to be more consistent in terms of functionality and more effective in terms of producing tangible deliverables. Some of these strengths are as follows:

- Contiguity and Relevance of its members to the Indo-Pacific: One of the biggest strengths of ADMM-Plus has been the geographic contiguity and relevance of its members to the Indo-Pacific security discourse. Observers have cited this as an important reason for ADMM-Plus being able to conduct better organised and more focused meetings with tangible outcomes.13

- Security Orientation of ADMM-Plus Leadership: Being led by the defence ministers and high-ranking military officials of its members has been a major strength of ADMM-Plus. The accomplishments of the ADMM-Plus have been attributed to the mission-mindedness of its leadership comprising national defence establishments with military assets and resources at their disposal. Observers have cited this as a major advantage of ADMM-Plus over ARF, EAS and SLD in making tangible contributions towards regional security cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.14

- Dual Leadership of EWG: The mechanism of the dual leadership of its EWG with an ASEAN nation and a Dialogue Partner has been another key driver for security cooperation under ADMM-Plus. This organisational setup empowers the EWGs by making them go beyond just a policy-drafting exercise. The dual-leadership of the ADMM-Plus EWGs enables them to achieve a substantial degree of practical and operational coordination.15 As a result, the key Indo-Pacific stakeholders are able to integrate their military resources and expertise for countering non-traditional threats through the ADMM-Plus.

Enduring Challenges and Limitations

The ADMM-Plus has acknowledged the potential of the power rivalries, strategic completion and territorial disputes in the Indo-Pacific region that can generate trust deficit among its members. As a result, the forum so far has restricted its agendas and mechanisms to address issues within the realm of non-traditional threats. This limits the scope of ADMM-Plus to comprehensively address the complex regional security challenges that arise from a combination of both traditional and non-traditional threats.

One such issue is the problem of Illegal, Unregulated and Unreported (IUU) fishing which is bound to overlap with the issue of contested maritime boundaries in the SCS region. This complex nexus between traditional and non-traditional security issues has been undermining the consensus among the ADMM-Plus members in envisaging long-term solutions to persistent regional security challenges.16

This undermining factor manifested during the Third ADMM-Plus meeting which was convened in Kuala Lumpur on 4 November 2015. A discord between the members regarding the SCS dispute sufficed and this prevented the members from arriving at a consensus regarding the issuance of a joint statement. The meeting happened just a week after US warships carried out a Freedom of Navigation (FoN) patrol around China’s artificially constructed islands in the Spratly archipelago.17

It has been reported that the original draft of the 2015 Joint Declaration contained the term ‘Freedom of Navigation’ to which all the members including China had agreed. But the US insisted that the ‘South China Sea’ must be clearly mentioned to avoid ambiguous wording. This was opposed by China and it was reported that China extensively lobbied to exclude the mention of SCS in the declaration.18 This issue eventually derailed the issuance of the Third Joint Statement and illustrated the reality of the overarching influence of the SCS dispute in the proceedings of ADMM-Plus.

The issuance of a joint statement by ADMM-Plus with the specific mention of SCS would have meant a major step forward for the establishment of PD mechanisms in the contested maritime space. Mechanisms like the Code of Conduct (CoC) and the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES) are essential for mitigating and managing the escalation of regional tensions.19 Although the latest joint statement issued by ADMM-Plus reiterated the forum’s commitment towards establishing CUES, the progress in conceiving such mechanisms has been rather slow.

This shows that the ADMM-Plus like ARF is struggling to go beyond the stage of confidence building in the roadmap that was envisaged in 1995. There is no doubt the ADMM-Plus has achieved tactical success by promoting task-specific military collaboration among its members in the non-traditional domain. But its strategic success can only be determined by its ability to transcend beyond the confidence-building stage and progress towards the establishment of PD mechanisms that will eventually pave way for conflict resolution in a highly contested maritime space.

Significance to India’s Act East Policy

Comprehensive Strategic Partnership can be interpreted as the pursuit of cooperation across a multitude of areas encompassing political, economic, social, cultural and military collaborations.20 With the elevation of India–ASEAN relations to the level of Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, it is imperative that defence cooperation become an intrinsic element of this partnership. Under the ‘Act East’ policy, India has been having robust defence cooperation with individual ASEAN nations at the bilateral level. The need for multilateral initiatives for building trust and confidence in the Indo-Pacific, though, is very important.

Taking into context the evolving dynamics of power rivalries in the Indo-Pacific and their impact on India’s national interests, the 2010–11 Annual Report of the Ministry of Defence describes ADMM-Plus as an effort to establish an open and inclusive security architecture in the region. 21 The report further describes India’s involvement in the ADMM-Plus as a vital component of its larger effort for building a progressive and multifaceted partnership with the ASEAN nations.22

Since the establishment of ADMM-Plus, India has played a leading role in its initiatives by employing its military assets and expertise in various FTE and TTX across all the EWGs. India co-chaired the first cycle of the EWG on HMA with Vietnam from 2014 to 2017.23 During this time, India conducted a large-scale FTE called Force 18 on HMA and PKO on its soil involving all the nations of the ADMM-Plus in March 2016. The knowledge gained through this exercise was instrumental in enhancing the capabilities of ASEAN’s Regional Mine Action Centre (ARMAC) in Cambodia.24

India went on to co-chair the third cycle of EWG on MM with Myanmar between 2017 and 2020.25 As part of this, the Indian Army Medical Corps conducted the first-ever standalone FTE on MM under the ADMM-Plus umbrella in March 2019 in Lucknow.26 Currently, India is co-chairing the EWG on HADR with Indonesia. The series of activities under this EWG started in 2020 and will complete in 2024.27 Through the analysis of the joint statement and the RM’s statement in the latest iteration of the ADMM-Plus, it can be inferred that the forum will play an instrumental role in enhancing the strategic depth between India and ASEAN in the following areas:

- Countering New-Age Terrorism: In his address at the Ninth ADMM-Plus meeting, the RM reiterated the need for urgent and resolute global efforts for countering terrorism. He also underscored the need for ADMM-Plus nations to collaborate on countering and degrading the ability of terrorist organisations to utilise new-age technologies.28 He was referring to the use of cyberspace and other niche technologies like drones by terrorist organisations for sustaining their activities. It must be noted that the fourth Joint Statement of ADMM-Plus released in 2018 was thematically dedicated to countering the various facets of new-age terrorism, including the degradation of terror financing.29 Hence, the ADMM-Plus will be playing a critical role in enhancing cooperation between India and ASEAN in envisaging a sustained and comprehensive approach to counter new-age terrorism.

- Advocating for a Free and Open Indo-Pacific: India has repeatedly advocated for a free and open Indo-Pacific across various multilateral forums. India is amongst the several Indo-Pacific Nations that have repeatedly expressed concern over the threats to FoN and Overflight by China in contested regions like SCS. All the recent joint statements issued by ADMM-Plus have unequivocally called for protecting FoN and Overflight in the region. Through this forum, India can play a constructive role in the establishment of PD mechanisms necessary for promoting a free and open Indo-Pacific

- Enhancing the level of Interoperability between India and ASEAN militaries: A day before the Ninth ADMM-Plus meeting, the India–ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting was convened on 22 November 2022. Here, Raksha Mantri called for further expanding the scope and depth of India–ASEAN defence relations through military-centric initiatives.30 To this end, ADMM-Plus is an important avenue for promoting collaboration and enhancing interoperability between Indian and ASEAN militaries in countering a range of security challenges in the Indo-Pacific that are covered through the EWGs.

Conclusion

In the 12 years since its establishment, ADMM-Plus has achieved remarkable success in becoming an avenue for promoting security cooperation between the major powers in a region that is characterised by strategic competition. This was reflected in the Defence Minister’s address at the Seventh ADMM-plus meeting, where he described the platform as the fulcrum of peace, stability and rules-based order in a region with visible strains.31 Although the ADMM-Plus has been successful in promoting security cooperation in the non-traditional domain, its success in the long run would hinge upon its ability to forge consensus among its members regarding the establishment of PD mechanisms. For India, the ADMM-Plus is very important considering India’s endeavours to increase its strategic depth with the ASEAN nations through the ‘Act East’ policy. India’s proactive participation in ADMM-Plus in the past and the prospects of future collaboration have clearly illustrated that the forum will be a key driver of the comprehensive strategic partnership between India and ASEAN.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “Vice President Leads Delegation at the 19th ASEAN-India Summit in Cambodia”, Vice President’s Secretariat, India, 12 November 2022.

- 2. Tan Seng Chye, ‘Strengths and Weakness of the ADMM and ADMM-PLUS’, in “Roundtable on the Future of the ADMM/ADMM-Plus and Defence Diplomacy in the Asia Pacific”, RSIS, Policy Report, February 2016, p. 10.

- 3. “ASEAN Regional Forum”, ASEAN.

- 4. “1995 The ASEAN Regional Forum: A Concept Paper”, ASEAN Regional Forum, 1 August 1995, p. 3.

- 5. See Seng Tan, “A Tale of Two Instituions: The ARF, ADMM-Plus and Security Regionalism in the Asia Pacific”, Contemporary Southeast Asia, Vol. 39, No. 2, August 2017, pp. 259–64.

- 6. “Vientiane Action Programme 2004-2010”, ASEAN, p. 4.

- 7. Siew Mun Tang, “ASEAN and the ADMM-Plus: Balancing between Strategic Imperatives and Functionality”, Asia Policy, Vol. 22, July 2016, p. 76.

- 8. “Hanoi Joint Declaration on the First ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus”, Hanoi, 12 October 2010.

- 9. “6th ADMM-Plus EWG on Maritime Security Meeting”, Ministry of Defence, Brunei Darussalam, 1 October 2013.

- 10. Kaewkamol Pitakdumrongkit, “Military Medicines Cooperation under the ADMM-Plus Progress, Challenges and Ways Forward”, RSIS, 2016.

- 11. “Third ASEAN Military Medicine Conference”, Brunei Darussalam, May 2021.

- 12. “Our Eyes Initiatives Concept Paper”, 19 October 2018, p. 2.

- 13. Gurjit Singh, “Is the ASEAN Regional Forum still relevant ?”, Observer Research Foundation, 19 August 2021.

- 14. See Seng Tan, “The ADMM-Plus: Regionalism that Works?”, Asia Policy, No. 22, July 2016, pp.70–75.

- 15. Siew Mun Tang, “ASEAN and the ADMM-Plus: Balancing between Strategic Imperatives and Functionality”, Asia Policy, No. 22, July 2016, pp. 76–82.

- 16. Lis Gindarsah, ‘Defence Diplomacy in Southeast Asia: A Review’, in “Roundtable on the Future of the ADMM/ADMM-Plus and Defence Diplomacy in the Asia Pacific”, RSIS, Policy Report, February 2016, p. 17.

- 17. Yeganeh Torbati and Trinna Leong, “ASEAN Defense Chief to Agree on South China Sea Statement”, Reuters, 4 November 2015.

- 18. Ken Jimbo, ‘The ADMM-Plus: Anchoring Diversified Security Cooperation in a Three-Tiered Security Architecture’, in “Roundtable on the Future of the ADMM/ADMM-Plus and Defence Diplomacy in the Asia Pacific”, RSIS, Policy Report, February 2016, p. 28.

- 19. “Joint Declaration by the ADMM-Plus Defence Ministers on Defence Cooperation to Strengthen Solidarity for a Harmonised Security”, ADMM-Plus, 23 November 2022.

- 20. “The Concepts of Comprehensive Security and Cooperative Security”, Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific, p. 2.

- 21. “Annual Report 2010-11”, Ministry of Defence, Government of India, p. 4.

- 22. Ibid.

- 23. “Annual Report 2013-14”, Ministry of Defence, Government of India, p. 194.

- 24. Prashanth Parameswaran, “India Concludes ‘Watershed’ Military Exercise with ASEAN-Plus Nations”, The Diplomat, 11 March 2016.

- 25. “Annual Report 2017 – 18”, Ministry of Defence, Government of India, p. 173.

- 26. “Annual Report 2018 – 19”, Ministry of Defence, Government of India, p. 122.

- 27. “Brief Note on ADMM Plus”, Indian Mission to ASEAN (Jakarta), 2021.

- 28. “Raksha Mantri Participates in 9th ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus in Cambodia”, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Defence, Government of India, 23 November 2022.

- 29. “Joint Statement by the ADMM-Plus Defence Ministers on Preventing and Countering the Threat of Terrorism”, ASEAN, 20 October 2018.

- 30. “Raksha Mantri & his Cambodian Counterpart Co-chair Maiden India-ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Siem Reap”, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Defence, Government of India, 22 November 2022.

- 31. “ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meet has Become Fulcrum of Peace and Stability”, ANI, 10 December 2020.