You are here

The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Implications for Regional Security

Summary

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, dating back to the Soviet times, continues to impact regional geo-political, geo-economic and strategic trends. The interests of major regional and extra-regional powers remain crucial in shaping the conflict.

Azerbaijan denied Armenia’s Prime Minister Nicol Pashinyan’s accusations about planning a military provocation in Nagorno-Karabakh on 7 September 2023. The Armenian leader’s statements came after reports of Azerbaijani troop movement across the disputed borders. These verbal confrontations have further fuelled tensions between the warring neighbours, who have been embroiled in constant ceasefire violations. The events have derailed the ongoing efforts to find sustainable peace in the South Caucasus region. The conflict, dating back to the Soviet times, continues to shape regional geo-political, geo-economic and strategic trends.

Historical Background

The root cause of the conflict lies in the formation of the Transcaucasia Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) in 1921 under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin. This was followed by the Soviet People’s Commissar of Nationalities, Joseph Stalin, shifting control of Nagorno-Karabakh to the Azerbaijani side of the Republic.1 This decision sowed the seeds for Armenia’s festering resentment, demonstrated in their continuous attempts to reverse the status quo. Unlike Azerbaijan’s Turkic population, a majority of ethnic Armenians continue to primarily reside in the Nagorno-Karabakh region.

Notably, the dispute persisted even after the dissolution of the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and formation of the three separate Caucasus Republics in 1936. In 1988, when the Soviet Union was nearing dissolution, the Armenian population, backed by Armenia’s SSR in Nagorno-Karabakh, protested against the Azerbaijani government and demanded independence.2 This resulted in all-out clashes between the two ethnic communities in the Nagorno-Karabakh region. The conflict escalated following the Soviet Union’s collapse amidst the two nations gaining independence. Nagorno-Karabakh emerged victorious in 1994, and the territory remained independent from Azerbaijani control.3 Despite being victorious, the region was primarily dependent on Armenia until 2020.

The Second Armenia–Azerbaijan War

The frozen conflict over the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh reignited in 2020 marked by the second Armenia–Azerbaijan war. It ended up altering the status quo. The war led to Azerbaijanis establishing control over large swathes of Nagorno-Karabakh following the massive military support, mainly drones, from Türkiye, which, in fact, proved to the proverbial game changer.4

It was also during this time that Russia deployed its peacekeepers in the Lachin corridor to prevent re-escalation of the conflict as per the agreement on the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh ceasefire agreement. The significance of the Lachin corridor can be gained from the fact that it is not only a humanitarian corridor but also a lifeline connecting Armenia with the people of Nagorno-Karabakh for movement of resources. The ongoing blockade of the corridor by Azerbaijani ‘eco-activists’ has reportedly created new humanitarian challenges for Nagorno-Karabakh amidst dwindling supplies and surging demand for essential commodities.

Yerevan’s Perspective

Republic of Artsakh (Armenian term for Nagorno-Karabakh) has been viewed as an extension of the Greater Armenian-Artsakh Connect5 , given its sizeable Armenian majority population (95 per cent population). Notably, Armenia has been viewed as Nagorno-Karabakh’s leading security provider by the territory6 and has a strong identity-based and historical connection with locals.

The Ottomans, who ruled the Armenians until the First World War, have been accused by the latter of committing the Armenian genocide between 1915 and 1917.7 The Armenians believe that the Azerbaijanis, who are ethnic Turks, aim to emulate the Ottomans, perceiving the recent events as an extension of the genocide.8 Moreover, Armenians have accused the Azerbaijanis of reviving their inter-generational trauma of the Armenians by torturing Nagorno-Karabakh’s ethnic Armenians. 9

Another major factor that has fuelled Armenia’s current reaction to the conflict is its Prime Minister Nicol Pashinyan. Despite being re-elected in a snap election, his decisions have spurred protests by both locals and diaspora, who have called for his resignation. Recently, the Armenian Prime Minister recognised Azerbaijani sovereignty over 86,000 kilometres of territory, including Nagorno-Karabakh.10 This worsened his approval rating, down to 14 per cent, among the population.11

Notably, his statements and perceived disregard for Nagorno-Karabakh’s significance for the larger Armenian society stems from a lack of connection to the conflict zone, unlike his predecessors. The first President, Levon Ter Petrosyan, was involved in the protests in the Soviet era and led Armenia against Azerbaijan during the First War. The other two leaders of Armenia, Robert Kocharyan and Sergh Sargasyan, were born in Stepanakert, Nagorno-Karabakh’s capital.

Baku’s Perspective

For the Azerbaijanis, international recognition has been one of its trump cards when discussing the conflict. For example, the UNSC Resolution 884 on 12 November 1993 affirms Nagorno Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan.12 Azerbaijan has also frequently invoked the Soviet Union’s decision to transfer Nagorno-Karabakh to the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic.

For the Azerbaijanis, the re-establishment of control over Nagorno-Karabakh was a promise waiting to be fulfilled by their incumbent leader, Ilhan Aliyev, since 2008.13 Meanwhile, efforts are underway to facilitate the return of the ‘displaced Azerbaijani’ population, i.e., those forced out from Nagorno-Karabakh during the First War.

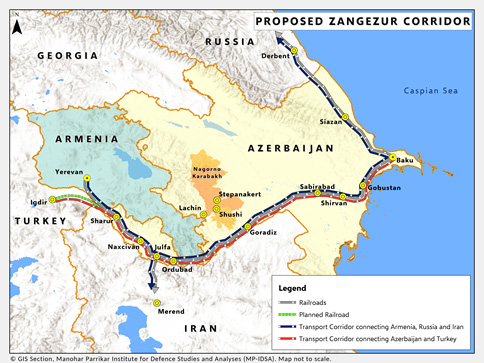

Another corridor of significant importance to the leadership in Baku is the Zangezur (Syunik) Corridor. The idea of the corridor came into discussion only after the conflict in 2020. This proposed corridor would connect Azerbaijan with its exclave, Nakhichevan, through Syunik, a territory within Armenia. Additionally, it would ensure Türkiye’s direct land connection to Azerbaijan from Armenian territory. The corridor, if implemented, would provide a transportation route from Baku to Kars in Turkiye. Until now, Türkiye had only one border connected with the Azerbaijani exclave Nakhichevan, which would be connected with Baku if the corridor was established.

Simultaneously, Azerbaijan has established a checkpoint near the Lachin Corridor. This has resulted in some Azerbaijani eco-protestors14 blocking the corridor, affecting the local population of Nagorno-Karabakh. The corridor is critical for transporting goods and services for the local population, and therefore, any obstruction can deprive people of essential supplies.

The Nagorno-Karabakh Perspective

With a predominantly ethnic Armenian leadership and social structure, locals see the conflict as integral to independence from Azerbaijan.15 The small Azerbaijani presence, which existed before the collapse of the Soviet Union, has aspired to live under Azerbaijan’s control, now a possibility after the 2020 war.16 While the majority community has appreciated Armenia’s involvement in Nagorno-Karabakh, they have expressed disappointment with Nicol Pashinyan’s administration.17 The public has demanded a more proactive stance from Armenia, reminiscent of its past efforts.18

Since 2020, amidst the territorial changes, the locals’ main concern has been their future treatment by Azerbaijani leadership, considering the ongoing hostility between the ethnic groups as well as between Armenia and Azerbaijan. These suspicions have heightened due to the Azerbaijani blockade in the Lachin Corridor. The embargo has invited sharp criticism from Armenia as well as regional and major extra-regional powers.

Notably, the United States, European Union, United Nations and France have been critical of the Azerbaijani ‘eco-protestors’ actions.19 Genocide Watch, a prominent genocide-related organisation, has referred to the blockade as creating a genocide-like situation. It has placed the territory on Stage 9 (Extermination) and Stage 10 (Denial) of genocide.20

At the same time, Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh have frequently referred to Azerbaijanis committing cultural genocide through churches and Khatchkars’ (Armenian Crosses) destruction.21 These debates on genocide coincide with the Armenian understanding of the conflict’s current phase as an extension of the genocide carried out by the Ottomans. On the other hand, the Azerbaijanis have denied such claims and have rather blamed Armenia for provocation.22

Role of Major and Regional Powers

Russia and Iran are considered Armenian allies whereas Türkiye and Israel back Azerbaijan. At the same time, the United States and the European Union (EU) appear to be seeking to expand their regional footprint. Russia remains one of the region’s key stakeholders concerning the conflict. Moscow has historically been connected to the conflict given their shared Soviet legacy. Russians have also been credited, mainly by Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, for trying to find a peaceful solution with their constant involvement in the various peace process. Russians brokered the 2020 peace deal, which involved placing Russian peacekeepers in the controversial Lachin corridor.

However, Russia has drawn criticism from the Armenian leadership for its perceived lacklustre efforts to find peace through the Collective Security Treaty Organisation.23 The Armenians expected a more proactive involvement similar to the one in Kazakhstan during the January 2022 protests. This is by virtue of Yerevan being a member of the CSTO with Russia having a military base in Gyumri.

Armenia and Azerbaijan have been part of the European Union’s Eastern Partnership since 2009. However, Azerbaijan is considered closer to the EU than Armenia given the latter’s membership in Russia dominated Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) and CSTO. Notably, Europeans have traditionally supported Azerbaijanis due to Armenia’s robust partnership with Russia. Nevertheless, the somewhat strained relationship between Russia and Armenia amidst European efforts for peace is being increasingly viewed positively by Armenian leaders including inviting the peace missions.24 This indicates a potential Armenian shift towards Brussels in the long term.

The EU has led peace missions and organised several meetings between government officials to establish regional peace. For example, the EU established two EU Missions; the first lasted for two months (October 2022–December 2022), and the second would be present in the Armenian territory till 2025, the same year the Russian peacekeepers would leave Lachin.25 However, the EU mission’s mandate is limited to Armenia due to Azerbaijan’s refusal to allow them into Azerbaijani territory.26 This has, however, not affected the relationship between the EU and Azerbaijan.

The United States’ involvement in this region could be linked to exploiting any vacuum created by Russia due to its involvement in Ukraine. The regional geopolitical turmoil could see the US attempt a more hands-on approach. The US has sought to play the role of a peace negotiator and moderator between the two governments while also being a member of the OSCE Minsk peacekeeping initiative. The latest involvement of the United States in the region is the 10-day routine military exercises it conducts with Armenia in Yerevan.27

Türkiye has a strong relationship with its Turkic brethren in Azerbaijan and sees it as a gateway to the region.28 Its ties with Armenia are almost non-existent, mainly due to the historical animosity that exists due to Türkiye’s predecessor—the Ottoman Empire. Since Türkiye sees Azerbaijan as its primary contact point, it has developed a strong relationship with it. Türkiye’s diplomatic and military support, particularly its famed Bakhtiyar drones, proved decisive for Azerbaijan in the second war.29

Iran remains a close partner of Armenia despite recognising Nagorno-Karabakh as Azerbaijani territory as per international norms. Iran’s closeness to Armenia is also co-related to its regional hostility with Israel, which provides Azerbaijan with 70 per cent of its total military supplies.30

Additionally, Iran fears the instigation of Azerbaijani nationalistic fervour within its borders.31

This threat has existed since the 1990s with the first post-soviet Azerbaijan President, Abulfaz Elchibey, threatening to march to Tabriz (Azerbaijani-populated Iranian territory),32 to the current establishment of Ilhan Aliyev declaring the need to secure minority Azerbaijanis in Iran. He referred to them as his ethnic kin.33 Mahmudali Chehreganli, the self-proclaimed and exiled leader of South Azerbaijan (North West Iranian territory) National Awakening Movement, in an interview with state-run AZ TV, called for the overthrow of the Iranian leadership, terming it as hateful.34 Such threats have risen after the 2020 conflict, particularly after Azerbaijani successes on the battlefield.35

Meanwhile, Iran’s dispute with Azerbaijan is also regarding the establishment of Zangezur corridor, which would connect Baku with its enclave Nakhichevan, the closest border that Iran shares with Azerbaijan.36 Türkiye supports the corridor’s idea, whereas Iran and Armenia have been opposed to it.37 Iran fears that the corridor could block Iranian land connection to Armenia if it exists.38 This would also obstruct its connection with Georgia which bypasses Azerbaijan and Türkiye. It has led Iran to be vocal against any territorial changes within Armenia which could happen due to the corridor.

Conclusion

The frozen conflict, reignited in 2020, remains the key hurdle to sustainable peace in the Caucasus. It continues to undermine regional security. Amidst continued ceasefire violations and lack of peace treaty, the solution to the conflict appears to be a distant dream.

Meanwhile, the interests of regional and extra-regional powers remain crucial in shaping the conflict. Russia’s war in Ukraine may see Moscow cede ground to others in what has been Russia’s traditional sphere of influence. Recently, Armenia recalled its envoy to CSTO amidst murmurs of discontent with the military organisation remaining neutral in Armenia’s moment of national crisis. As such, the US and the EU in particular could seek to expand their footprints in the region amidst the overhang of Russia–West confrontation.

Notably, older peace formats, including the OSCE format for peace, which was instrumental in negotiating a peace deal during the 1990s, appear to have lost relevance. Instead, peace deals proposed by Iran and Türkiye have gained traction, thereby highlighting their growing regional influence in the Caucasus. However, given the strained relations of these countries with the warring nations, i.e., Iran with Azerbaijan and Armenia with Türkiye, the chances of concluding a credible peace treaty appear slim.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. Stalin had taken up the task of putting the Nagorno-Karabakh region within Azerbaijan mainly to placate a newly formed Turkish republic under Kemal Ataturk. See “Stalin’s Legacy: The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict”, Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, 6 August 2013.

- 2. Niall M. Fraser, Keith W. Hipel, John Jaworsky and Ralph Zuljan, “A Conflict Analysis of the Armenian-Azerbaijani Dispute”, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 34, No. 4, December 1990, p. 658.

- 3. Shavarsh Kocharyan, “Why is the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict Still Not Resolved?”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Republic of Armenia, 2016.

- 4. “Second Karabakh War: Outcomes”, USC Institute of Armenian Studies, 1 December 2020.

- 5. The Greater Armenian-Artsakh Connection is the connection that binds the two territories into one more significant entity. The two are connected by history, territory, and culture, and these ties secure the two as one greater nation and people. See “The Armenian-Artsakh Connection”, Armenian General Benevolent Union Armenia, November 2020.

- 6. “Yerevan Urged to Fulfill its Obligation as Artsakh’s ‘Security Guarantor’”, Asbarez, 5 April 2022.

- 7. “Armenian Genocide (1915-1923)”, Armenian National Institute, 2023.

- 8. Christina Maranci, “What Cultural Genocide Looks Like for Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh”, Time, 12 October 2023.

- 9. Lalai Manjikian, “Facing Intergenerational Wounds”, The Armenian Weekly,15 October 2020.

- 10. Lillian Avedian, “Pashinyan Ready to Recognize Artsakh as Part of Azerbaijan”, The Armenian Weekly, 24 May 2023.

- 11. “Public Opinion Survey: Residents of Armenia”, Center for Insights in Survey Research, January–March 2023.

- 12. “Resolution 884 (1993) / adopted by the Security Council at its 3313th meeting”, United Nations Security Council, 12 November 1993.

- 13. “Aliyev Sworn In, Pledges To Restore Control Over Separatist Region”, Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty, 24 October 2008.

- 14. The Azerbaijani protestors claim they are protesting against the alleged illegal Armenian exploitation and looting of natural resources in the Karabakh region. See Burc Eruygur, “Protests by Azerbaijani Environmental Activists on Lachin Road Reach 100 days”, Anadolu Ajansı, 21 March 2023.

- 15. “The Referendum on Independence of the Nagorno Karabakh Republic”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Republic of Artsakh, 2023.

- 16. “Azeri Refugees Long to Return to Nagorno-Karabakh”, France 24, 25,September 2023.

- 17. Narek Aleksanyan, “Yerevan Protesters Demand Pashinyan’s Resignation”, Hetq, 15 September 2022.

- 18. Howard Amos, “Thousands Protest in Armenia Over Military Strike on Nagorno-Karabakh”, The Guardian, 20 September 2023.

- 19. Olesya Vartanyan, Zaur Shiriyev, Olga Oliker and Oleg Ignatov, “New Troubles in Nagorno-Karabakh: Understanding the Lachin Corridor Crisis”, International Crisis Group,22 May 2023.

- 20. Nathaniel Hill, “Genocide Emergency: Azerbaijan’s Blockade of Artsakh”, Genocide Watch, 24 February 2023.

- 21. Hamlet Petrosyan and Haykuhi Muradyan, “The Cultural Heritage of Artsakh/Karabakh at the Cross-Hairs of Attacks”,Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports of The Republic Of Artsakh, 2022.

- 22. Catherine Womack, “Historic Armenian Monuments were Obliterated. Some Call it ‘Cultural Genocide’”, Los Angeles Times, 7 November 2019.

- 23. Armenia’s disappointment has been expressed openly in its refusal to host training exercises and even abandoning its quota for the post of the Deputy Secretary General. See “Armenia to Leave the CSTO Russian Military Bloc? Opinion from Yerevan”, JAM News, 10 March 2023.

- 24. Kirill Krivosheev, “Could the New EU Mission Sideline Russia in Armenia-Azerbaijan Settlement?”, Carnegie Politika, 16 February 2023.

- 25. Ibid.

- 26. “Baku rejects idea of deploying EU mission to Azerbaijan’s territory near Armenian border”, Tass News Agency, 15 October 2022.

- 27. “EAGLE PARTNER 2023: Armenia-United States Joint Military Exercise Commences”, ArmenPress, 11 September 2023.

- 28. “Azerbaijan - Our Gateway to Caucasus, Says Izmir Chamber of Commerce”, AzerNews, 21 May 2022.

- 29. Hülya Kınık, “The Role of Turkish Drones in Azerbaijan’s Increasing Military Effectiveness: An Assessment of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War”, Insight Turkey, Vol. 23, No. 4, 14 December 2021.

- 30. Isabel Debre, “Israeli Weapons Quietly Helped Azerbaijan Retake Nagorno-Karabakh — Sources, Data”, Times of Israel, 5 October 2023.

- 31. Alexander Yeo and Emil A. Souleimanov, “Iran-Azerbaijan Tensions and the Tehran Embassy Attack”, The Central Asia and Caucasus Analyst, 8 May 2023.

- 32. Eldar Mamedov, “Perspectives | In Azerbaijan, Turkish Leader Has Eyes on Iran”, EurasiaNet, 14 December 2020.

- 33. “Safety, Rights, Well-being of Azerbaijanis Living Abroad – Of Great Importance to Azerbaijan – President Ilham Aliyev”, Trend News Agency, 21 October 2022.

- 34. Joshua Kucera and Ulkar Natiqqizi, “Via Official Media, Iran and Azerbaijan Issue Escalating Threats”, EurasiaNet, 9 November 2022.

- 35. Ibid.

- 36. A corridor from Nagorno-Karabakh, through Armenian territory and connecting Azerbaijan with its exclave Nakhichevan, which borders Iran. See “What is the Zangezur Corridor and why does it matter to Eurasia?”, TRT World, September 2022.

- 37. Umud Shokri, “Why Iran Opposes Azerbaijan’s Zangezur Corridor Project”, Gulf International Forum, 28 September 2022.

- 38. Ibid.