Source : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Provinces_closed_in_Turkey_for_prevention_COVID-19.svg

You are here

Turkey Struggles to Tackle COVID-19

Like other parts of the world, West Asia (or the Middle East) too is hit hard by the spread of COVID-19 and Turkey is no exception. In fact, Turkey is the second worst hit country after Iran in the region. As of April 13, 2020, Turkey reported 56,956 confirmed cases of COVID-19; while 3,446 people recovered, and 1,198 died because of the infection.1 Globally, Turkey has reported the ninth-largest cluster of cases. In comparison to the other global hotspots such as the United States, Italy, Spain and others, Turkey has reported a lower rate of fatalities. However, the prevailing political and economic conditions in the country have complicated its response to the pandemic.

Between the first confirmed case of COVID-19 recorded on March 112 and the first reported death on March 17,3 the number of cases in the country jumped to 191.4 The rapid spread of infection was mainly attributed to the government’s failure to stop the inflow of people, goods and services from abroad including from China and Iran until mid-February, and a slow response in restricting the movement of people, goods and services within the country. It was not until March 27 that Turkey decided to completely stop all international flights and restrict domestic movements.5 By this time, the number of cases had already reached 6,000 and about 90 had perished from COVID-19.6 Despite the curbs coming into effect, and assurances from the government, the number of cases continued to rise rapidly. The partial nature of curbs and the failure of the local administration to take adequate preventive measures further compounded the situation. In the first week of April, Turkey reportedly had “the fastest rising number of confirmed cases in the world.”7

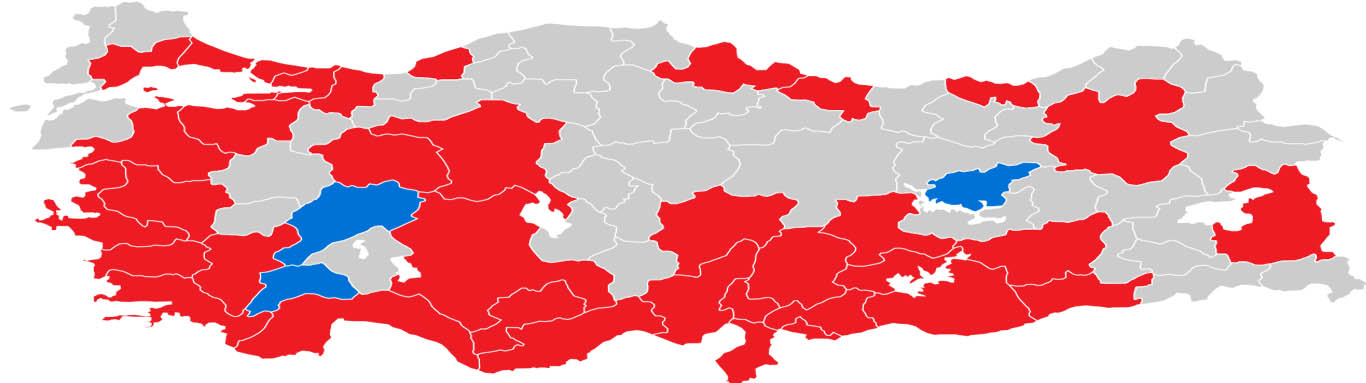

The first set of curbs and restrictions announced on March 27 included a nationwide restriction on movement either by roads, railways or airways and suspension of all international flights. Domestic movement was allowed only in case of emergencies with permission from local governors. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan while announcing the curbs urged people to “voluntarily quarantine” in case they suffer from any illness or symptoms of flu.8 He especially urged the aged population beyond 65 years to remain inside their homes and follow social distancing. Other measures included a complete lockdown in 12 population centres in the Black Sea provinces of Rize and Trabzon.9 Erdogan also announced partial lockdown in 30 metropolitan areas in the country including the capital Ankara and country’s financial hub Istanbul, as well as the two other most populous cities of Kocaeli and Izmir where only limited public transport was allowed and curbs were put on non-essential services.10

As the situation continued to deteriorate due to a combination of policy failure and non-compliance of the precautionary measures, the government announced new measures on April 3 to completely restrict the movement of people above 65 years and below 20 years, as well as the movement of private vehicles in 31 provinces including in major metropolitan areas.11 Turkey announced the formation of pandemic board in all 81 provinces to monitor the situation at the local level and take quicker decisions for lockdown in case of necessity. Schools, universities and other educational institutions, as well as public places including archaeological sites and picnic spots have also been closed though places of worship have only been directed to maintain social distancing. In the meanwhile, Turkey has mandated the use of masks in public and is trying to boost healthcare capacity by building temporary facilities to provide treatment to those affected.12 The Turkish National Assembly is also debating a bill to protect the healthcare workers with increased penalty on any form of violence against them.

The country is facing an uncertain economic situation. The fear of a global recession because of the uncertainties and near halting of economic activities has all the countries preparing for the worst. For Turkey, already facing economic slowdown over the last three years because of the currency and debt crisis and also due to the economic crises in Europe, the economic impact of the pandemic could be even more debilitating. The country had only recently begun to recover from economic problems. After witnessing negative growth in 2018, the Turkish economy showed signs of growth in 2019 riding on fiscal measures introduced by the government and improved foreign trade with countries in Central Asia, Arab Gulf as well as China.13 Though the growth was in decimal numbers, the World Bank had projected that given the signs of recovery the economy will grow by 3 per cent in 2020. Other economic indicators including current account deficit and inflation had also shown improvement in 2019. The banking and finance sectors too were witnessing a recovery.14 However, with challenges arising from the COVID-19 pandemic, the growth projections are likely to remain unmet.

Though Turkey’s central bank has denied that the economy will be severely affected arguing that with “its dynamic structure, the Turkish economy will be one of the economies to see the least damage”.15 However, international rating and economic assessment agencies warn that given its vulnerabilities, the Turkish economy is expected to be “hit hardest” among the G20 nations from the “unprecedented shock to the global economy caused by the corona virus.”16 Moody revised the forecast for economic growth for 2020 from 3 per cent to 1.4 per cent. In a report released recently, it is projected that Turkey’s GDP will undergo “a cumulative contraction” of about 7 per cent in the second and third quarters of 2020.17

In fact, one of the reasons for the slow response of the government was to avoid hampering the economic recovery. On April 5, two days after the second set of restrictions came into force, Turkey relaxed the restrictions for people under 20-years working in farm or agriculture sector or in private enterprises to mitigate the impact on the economy. This has fuelled criticism from the opposition leaders who argue that the government’s move will hamper the fight against the pandemic.

The main opposition leader from the Republican People’s Party (CHP), Kemal Kilicdaroglu, not only criticised the delay in effecting curbs but also underlined that the half-hearted measures might not be enough given the magnitude of the situation.18 Kilicdaroglu said, “At this stage, it is evident that we need a comprehensive, wide and effective stay-at-home and quarantine” against the “voluntary quarantine” being urged by the government.19 He further noted that given the gravity of the situation, “It is not possible to solve this issue with campaigns like ‘Stay Home Turkey’ and by leaving it to the will and initiative of our citizens while not providing any wage or job security and abandoning them to fate.”20 Other opposition parties too have joined CHP in criticising the government for its handling of the situation and also for intensifying the political squabbling within the country.21

Like many other countries in the world, Turkey was caught unprepared to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. The political divisions and economic challenges facing the country have complicated the government’s response, putting the population at risk and threatening to undermine the popularity of President Erdogan.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “Coronavirus Resource Center”, Coronavirus Resource Centre, Johns Hopkins University (Accessed April 13, 2020).

- 2. Faruk Zorlu, “Turkey confirms first case of coronavirus”, Anadolu Agency, March 11, 2020 (Accessed April 10, 2020).

- 3. “Turkey reports first 2 coronavirus deaths amid jump in cases”, Al Jazeera, March 19, 2020 (Accessed April 10, 2020).

- 4. Ibid.

- 5. Tuvan Gumrukcu, “Turkey limits transport, opposition calls for 'stay at home' order over virus”, Reuters, March 28, 2020 (Accessed April 10, 2020).

- 6. Ibid.

- 7. Bethan McKernan, “Turkey's Covid-19 infection rate rising fastest in the world”, The Guardian, April 07, 2020 (Accessed April 10, 2020).

- 8. Ibid.

- 9. Ezgi Akin, “Turkey imposes first curfew as coronavirus infections surge”, Al-Monitor, March 27, 2020 (Accessed April 10, 2020).

- 10. “Turkey suspends all international flights, expands restrictions”, Al Jazeera, March 28, 2020 (Accessed April 10, 2020).

- 11. Aykut Karadag and Orhan Onur Gemici, “Turkey begins Implementing New COVID-19 Measures”, Anadolu Agency, March 04, 2020 (Accessed April 10, 2020).

- 12. Emin Avunduklooglu, “Turkey: New measure would protect healthcare workers”, Anadolu Agency, April 09, 2020 (Accessed April 10, 2020).

- 13. “Turkey Overview”, The World Bank, October 18, 2019 (Accessed April 10, 2020).

- 14. Ibid.

- 15. “Turkey's economy to be among least damaged by pandemic, central bank official says”, Daily Sabah, March 29, 2020 (Accessed April 10, 2020).

- 16. “Turkey’s economy most vulnerable in G20 to COVID-19, Moody’s says”, Ahval News, March 26, 2020 (Accessed April 10, 2020).

- 17. Ibid.

- 18. Tuvan Gumrukcu, no. 5.

- 19. Ibid.

- 20. Ibid.

- 21. Orhan Kemal Cengiz, “Erdogan claims monopoly on goodness, but it might backfire”, Al-Monitor, April 06, 2020 (Accessed April 10, 2020).