Central Asia–Japan Relations: Benefits and Challenges

- December 27, 2024 |

- IDSA Comments

Japan’s interest in the Central Asian Republics (CARs) has deepened in the recent decades. The ‘Central Asia plus Japan Dialogue’ was traditionally held at the Foreign Ministers level. It was, for the first time, elevated to a Heads of Government meeting in August 2024 in Astana. However, the meeting was unexpectedly cancelled due to a major earthquake warning issued by the Japan Meteorological Agency.

Post the collapse of the Soviet Union, Japan established diplomatic relations with the CARs. Several steps were taken since then by Japan to explore potential avenues of collaboration with the region.1 In 1996, Prime Minister Hashimoto Ryutaro introduced the Silk Road Action Plan. The initiative sought to promote greater involvement of Japanese companies in the oil and gas-rich economies of Central Asia. The CARs and Japan also engaged through multilateral institutions to promote the Japanese vision of stability in the Central Asian region.

In 2004, Japan enhanced its regional engagement by establishing the Central Asia Plus Japan initiative.2 Japan provided technical assistance, loans and grants to support vital regional infrastructure projects such as transportation networks, energy initiatives and connectivity improvements. These efforts aimed to bridge infrastructure gaps and promote regional economic integration by improving access to trade routes and energy networks. Interestingly, Turkmenistan, while upholding its policy of neutrality, decided to participate in the Central Asia Plus Japan meetings as an observer.3

How does Central Asia benefit from Japan?

Central Asia has gained substantial financial assistance for a variety of projects, particularly in infrastructure development, from Japan’s Official Development Assistance (ODA). These projects include the construction of roads, bridges and energy facilities, which aim to improve connectivity and bolster economic growth in the region. Disbursements in 2016, for instance, to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, amounted to ¥1158.29 million, ¥815.42 mln, ¥418.17 mln, ¥62.41 mln and 3207.74 mln respectively.4

Central Asia benefits from Japan’s technological expertise in various fields, including renewable energy, agriculture and manufacturing. By collaborating with Japanese companies, the CARs have accessed cutting-edge technology, enhancing productivity and innovation.5 In Uzbekistan, Mitsui & Co. and Komaihaltec are rolling out AI-powered traffic lights, designed to reduce congestion, and also promoting wind-powered smart cities.6 Additionally, Itochu and Kawasaki Heavy Industries, in collaboration with a state-owned company in Turkmenistan, are set to construct a plant that will produce gasoline from natural gas. They will also bring in technology aimed at reducing methane emissions from natural gas production.7

The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) supports human resource development by providing technical assistance and supports educational initiatives. Till 2022, Japan had welcomed around 12,100 trainees from Central Asian and Caucasus nations and sent approximately 3,300 experts to these countries to support human resource development initiatives.8 These efforts enhance local skills in various sectors, such as healthcare, education and governance, foster sustainable development and empower communities to effectively address regional challenges and improve overall quality of life.9

Furthermore, Japan actively contributes to building essential human resources for nation-building through various programmes such as the Project for Human Resource Development Scholarship, which allows young government officials and other participants to study in Japan. Additionally, initiatives like the Development Studies Program and efforts led by the Japan Center for Human Resources Development focus on cultivating skilled professionals for business and governance.10

Japan’s Interests in Central Asia

Japan has made investments in the oil and gas infrastructure in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.11 In 2009, during Turkmen President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow’s visit to Tokyo, several contracts were signed with Japanese companies, such as JGC Corporation, ITOCHU Corporation, Kawasaki Plant Systems Ltd and Sojitz Corporation, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Sojitz Corporation, Asahi Kasei Chemicals Corporation to increase Japanese participation in petrochemical, gas processing and other related sectors.12 In 2023, the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) signed a loan agreement with ENERSOK Foreign Enterprise LLC (ENERSOK) in Uzbekistan amounting up to nearly US$ 400 million for a 1600 MW natural gas-fired combined cycle power plant project.13

With Kyrgyzstan, Japan has signed a MoU on joint projects on green energy and has been in discussion for the development of renewable energy sources and construction of hydropower plants.14 Through its ‘project for introduction of clean energy’ in Tajikistan, Japan aims to promote clean energy utilisation.15 Japan has also partnered with Kazakhstan in uranium mining, which is a crucial resource for Japan’s nuclear energy industry.16

Japan also aims to assist in the sustainable development and green transition of Central Asia. Prior to the cancellation of former Prime Minister Kishida’s visit, it was anticipated that he would promote initiatives like decarbonisation in Central Asia, advocate for low-emission technologies, and provide help in creating value-added exports such as hydrogen and fertilisers derived from natural gas.17

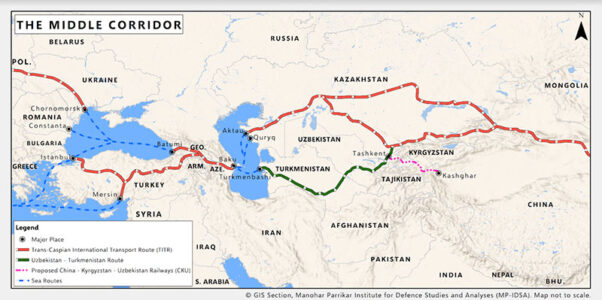

In addition to energy, Tokyo aims to enhance connectivity between Europe and Asia, by investing in transport networks like railways and highways, facilitating trade and economic integration. One such project was the Tashguzar-Kumkurgan New Railway Construction Project, funded by JICA in 2004.18 It was expected that during Kishida’s visit, discussions would be held regarding the Middle Corridor—a trade route linking Central Asia and Europe circumventing Russia—alongside a proposed 300 billion yen (US$ 2.1 billion) economic aid package from Japan.19

The conflict in Ukraine and the resulting sanctions have disrupted traditional trade routes, making the Middle Corridor, also known as the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR)—a valuable option for diversifying transport pathways.20 For Japan, the successful operationalisation of the Middle Corridor would enhance economic security, resource accessibility and diplomatic engagement with Central Asian and Caucasus nations.

A stable region is crucial for Japan’s aforementioned economic interests, as it will facilitate trade routes and access to valuable resources. Additionally, ensuring regional security is important, as instability can lead to conflicts that affect neighbouring countries and create wider geopolitical tensions. Japan has emphasised that

the cooperative relationship between the Central Asian countries and Japan contributes to the peace and stability not only for the Central Asian region but also for the international community as a whole.21

Cultural and educational exchanges are another important facet of Japan’s engagement. Historically, Japan promoted educational and leadership development through Japan Centres and JICA programmes, aiming to foster goodwill and mutual understanding between its citizens and those of Central Asia. Amidst Western sanctions on Russia, Japan recognises the need to diversify Central Asia’s workforce destination, and consequently could mitigate labour shortages, benefitting from the skilled Central Asian workforce.22

Challenges and Future Prospects

From a Central Asian perspective, Japan’s relationship with the region offers opportunities for economic growth, strategic partnerships and cultural engagement. Engagement with Japan not only offers significant benefits for the region and also furthers Japan’s own strategic and economic ambitions. However, there are some challenges in engaging with Japan, primarily due to Central Asia’s geopolitical dynamics.

Central Asia’s efforts to deepen ties with Japan are hindered by the dominant influence of China and Russia. Through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China has made significant investments in infrastructure and trade, establishing itself as the region’s largest economic partner. Due to the CARs’ geopolitical proximity, and historical and security ties with Russia, the former often tends to prioritise their relationship with the latter. This complex scenario makes it difficult for Japan to fully assert its presence, as Central Asian countries strive to maintain balanced ties with both the regional powers, i.e., Russia and China.

Japan’s ties with Central Asia have evolved amid the Ukraine war, highlighting both geopolitical and economic considerations. The conflict has prompted Japan to strengthen partnerships in Central Asia, emphasising energy security and diversification of supply routes. Japan has increased investments in Central Asian infrastructure and energy projects in recent years. Japan itself is seeking to reduce its dependence on Russia. Overall, the Ukraine war has reinforced Japan’s strategic interest in Central Asia, positioning the region as a crucial player in Japan’s broader economic and security framework.

Conclusion

The prospects for a stronger Central Asia–Japan cooperation remain promising. As Central Asian countries seek to diversify their foreign partnerships, Japan can play a key role in promoting regional stability and economic diversification, fostering mutually beneficial relationships. Through continued diplomatic engagement and collaboration in sectors like education, trade and technology, Japan has the potential to become an important partner in shaping Central Asia’s future growth and integration into the global economy.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. Timur Dadabaev, “Japan’s Search for Its Central Asian Policy: Between Idealism and Pragmatism”, Asian Survey, Vol. 53, No. 3, 2013, p. 514.

- 2. Christopher Len, “Japan’s Central Asian Diplomacy: Motivations, Implications and Prospects for the Region”, China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly: Energy and Security, Vol. 3, No. 3, November 2005, p. 142.

- 3. “Central Asia Plus Japan Dialogue/Foreign Ministers Meeting – Relations between Japan and Central Asia Enter a New Era”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 28 August 2004.

- 4. “Japan’s ODA Data for Kazakhstan”, “Japan’s ODA Data for Kyrgyz Republic”, “Japan’s ODA Data for Tajikistan”, “Japan’s ODA Data for Turkmenistan”, “Japan’s ODA Data for Uzbekistan”, Official Development Assistance, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.

- 5. “White Paper on Development Cooperation“, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2022, p. 114.

- 6. “Japan to Offer $2bn in Trade Support for Central Asia Projects”, Nikkei Asia, 6 August 2024.

- 7. Ibid.

- 8. “White Paper on Development Cooperation“, no. 5.

- 9. “Japan’s Official Development Assistance White Paper”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2006.

- 10. “White Paper on Development Cooperation 2022“, no. 5.

- 11. “How Japan is Charting a New Direction for Central Asia”, Japan Up Close, 22 December 2023.

- 12. “Turkmenistan, Japan to Ink Agreements on Cooperation in Oil and Gas Sector”, AzerNews, 21 August 2013.

- 13. “Project Financing for Syrdarya II Natural Gas-Fired Combined Cycle Power Plant Project in Uzbekistan”, Japan Bank for International Cooperation, 24 March 2023.

- 14. “Kyrgyzstan and Japan Agree to Cooperate in Green Energy”, The Times of Central Asia, 10 September 2024.

- 15. “Project for Introduction of Clean Energy by Solar Electricity Generation System”, Japan International Cooperation Agency.

- 16. “Japan and Kazakhstan: Nuclear Energy Cooperation”, Nuclear Threat Initiative, 12 March 2009.

- 17. “Central Asia Becomes Key Focus for Global Economic Partnerships”, Daryo, 10 September 2024.

- 18. “Tashguzar-Kumkurgan New Railway Construction Project – Project Brief”, JICA.

- 19. “Japan to Offer $2bn in Trade Support for Central Asia Projects”, no. 6.

- 20. “10 Priority Actions That Can Triple Trade in the Middle Corridor by 2030”, Brief, World Bank, 17 April 2024.

- 21. “Central Asia + Japan Dialogue/Foreign Ministers’ Meeting”, Joint Statement, 28 August 2004.

- 22. “Central Asia Plus Japan Summit Aims to Pioneer Sustainability, Connectivity, and Human Development”, The Diplomat, 8 August 2024.