FATF: In Need of Darker Shades of Grey

Summary: The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is known for policy innovation and flexibility. But when faced with jurisdictions like Pakistan that offer cooperation in form but not in substance, its listing regime has been largely ineffective. The present categorisation of lists—white, grey and black—may be too rigid to effectively address such risks. The grey list has very low economic or political costs as compared to the black list, which has led to a high threshold and barrier in taking effective action. This brief calls for more gradations between the grey and black lists as it may increase policy options and leverage.

Summary: The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is known for policy innovation and flexibility. But when faced with jurisdictions like Pakistan that offer cooperation in form but not in substance, its listing regime has been largely ineffective. The present categorisation of lists—white, grey and black—may be too rigid to effectively address such risks. The grey list has very low economic or political costs as compared to the black list, which has led to a high threshold and barrier in taking effective action. This brief calls for more gradations between the grey and black lists as it may increase policy options and leverage.

Introduction

After being deferred twice due to COVID-19, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Plenary meeting is now scheduled for 21-23 October, 2020. Leading up to this Plenary Meet one of its constituent bodies, the Asia Pacific Group (APG), met to review the pending cases, like that of Pakistan, pertaining to its jurisdiction. As if on cue, there was news of Pakistan’s vigorous efforts at passing new laws in compliance of its Anti Money Laundering/ Countering Financing of Terror (AML/CFT) obligations.1 Parallelly, there is increased speculation about whether Pakistan would be “black listed” or if it would it remain on the “grey list” or manage to revert back to the so-called “white list”. This sequence of events has been continuing for nearly two years now since Pakistan regressed to its “grey list” position since June 2018. As Pakistan continues to fail to meet the successive deadlines set by the FATF, the threats from the organisation are becoming shriller and, in response, so are protestations from Islamabad.

Is There a Political Cost?

The case of Pakistan offers a great vantage point in appreciating the challenges faced the FATF regime. Pakistan has been in and out of the grey list more than once. Having faced such close scrutiny, it has avoided effective implementation of the recommendations of the FATF on the one hand and also not being put on black list on the other.

Countries falling in “grey list” technically indicate that these jurisdictions have strategic deficiencies in their AML/CFT regime and they are considered for more regular monitoring. It also indicates that they have committed to remove such deficiencies in a time bound manner. In contrast, countries in the “black list” are those which have been reported for enhanced due diligence. Generally, the black list comprises of non-cooperative jurisdictions which do not commit to improve upon the strategic deficiencies in their AML/CFT regime.

Pakistan has undergone full mutual evaluation twice: the first was in 2009 and latest in 2019. Many of the AML/CFT risks flagged in both these Mutual Evaluation Reports (MER) are identical but MER-2019 is even more damning with Pakistan being non-complaint on 27 out of 40 Recommendations.2 The question that arises is: how did it get out of the grey list in 2015 and why did it re-enter in 2018? Did it substantially comply with FATF Recommendations from 2015-18? If yes, then why did it re-enter the grey list in 2018? If not, how did it come out in 2015?

The MER-2009 pointed out strategic deficiencies in Pakistan’s AML/CFT regime and, in consequence, it made political commitment at the highest level to address such deficiencies in a time bound manner. Concerned with the tardy pace of implementation, on June 24, 2011, the FATF observed: “The FATF is particularly concerned with the lack of implementation regarding Pakistan’s terrorist financing offence and calls upon Pakistan to demonstrate specific action (emphasis mine).”3 Subsequent to this, Pakistan was put on grey list on October 19, 2012. While grey-listing, FATF appreciated Pakistan efforts in some technical areas but remarked: “However, despite Pakistan’s high-level political commitment…Pakistan needs to enact legislation to ensure that it meets the FATF standards regarding the terrorist financing offence and the ability to identify, freeze, and confiscate terrorist assets (emphasis mine).”4

Pakistan came out of the grey list on February 27, 2015 with FATF remarking: “Pakistan will work with APG as it continues to address the full range of AML/CFT issues identified in its mutual evaluation report, in particular, fully implementing UNSC Resolution [United Nations Security Council Resolution] 1267 (emphasis mine).”5

It is worth mentioning here that FATF draws upon various international conventions and treaties and UN Security Council Resolutions (UNSCR) for legal sanctity and legitimacy. For CFT-related Recommendations, till then, it primarily drew upon UNSCR 1267 (1999), 1373 (2001) and the Terrorist Financing Convention, 2009.6 Apart from many other international terrorists historically living in or functioning from Pakistan, Hafiz Mohammad Saeed and his associates were put on UNSCR 1267 sanctions list as on December 10, 2008, vide UNSCR 1822 (2008).7 But as reported in The Dawn on January 25, 2015, just a month before Pakistan was taken off the grey list, Saeed had publicly “clarified” that these sanctions had been going on for the last six years and there was nothing serious about them, and that he would continue his activities.8 Thus, Pakistan got out of the grey list by adopting some legal measures in form but saving its “strategic assets” in content, which were sanctioned under UNSCR 1267. This failure on the part of FATF becomes even more glaring as by this time it had already adopted its new methodology of risk assessment in 2012-13, which took the effectiveness of the AML/CFT regime into account.9

Apparently, the only good reason on the FATF’s part in taking Pakistan out of the grey list in 2015 may be its decision-making style: once political commitment is made at the highest level, the FATF generally accepts the promise and/or only undertakes periodic reviews. So, the FATF relied upon assurances and took Pakistan out of the grey list in 2015 without actually considering the actual performance. This experience poses another question to the FATF: what does it mean to accept “political commitment from highest level” from a hybrid regime where de facto and de jure authority may not be co-located? And if the FATF accepts at face value promises which are not meant to be kept, what effect does this have on its credibility?

Pakistan is called a hybrid regime in the sense that writ of the elected government is limited in certain areas like security or foreign policy.10 The tussle between the elected government and the Pakistan Army regarding the policy to be adopted for Pakistan-based terrorist organisations is well documented (see the “Dawn Leaks”11 of 2017 or ex-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s speech dated September 21, 202012).

Indirectly acknowledging its lapse at prematurely taking Pakistan out of grey list in 2015, the FATF put it back on the list in June 2018. This time round the FATF has taken Pakistan for more regular periodic monitoring and it is trying to fix stricter deadlines, but the fact remains that even after the lapse of several such deadlines and warnings the FATF is not able to extract genuine policy action.

Despite being grey listed time and again, why is Pakistan is not effectively complying with FATF Recommendations? The answer may lie in its experience in manipulating and hoodwinking the FATF grey/black listing system in particular, and international community in general.

Starting from General Pervez Musharraf’s explicit pledge on January 6, 2004 to not allow Pakistan’s soil to be used to hosting international terrorist organisations till now, there have been many promises. These only proved to be a tactical short-term ploy to get out of a tight spot.13 It is not that the world is unaware of this.14 Most experts take Hafiz Saeed’s conviction in 2020 with a lump of salt and think that he has been convicted on very weak evidence so that he may be provided relief in appellate stages. According to Ayesha Siddiqa: “The complete court order that I was able to access and read indicates Islamabad’s willingness to take risks based on its understanding of the FATF. It is not seen entirely as a technical mechanism but as an instrument of power politics. This means there is an expectation that playing a favourable role in the US-Taliban peace agreement will bring dividends, such as the removal from the FATF’s grey list.”15

In the meantime, expecting impending trouble, Pakistan has washed its hands off its long-time strategic asset, Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM) Chief Maulana Masood Azhar. The Maulana and JeM are also proscribed under UNSCR 1267. This organisation claimed responsibility for the Pulwama attack of 2019 and was blamed for the Pathankot attack of 2016. In 2016, an FIR was also registered in Pakistan and JeM Chief Maulana Masood Azhar was taken into protective custody.16 Pakistan has avoided that inconvenience this time round and claimed that the Maulana along with his family remains untraceable.17

In Pakistan, many FATF Recommendations, which it has implemented and touts as achievements, are meant to fulfil a domestic political agenda. For example, money laundering, tax evasion and the issue of corruption has been used by the present regime against political rivals like Nawaz Sharif and Asif Ali Zardari. Issues of tax evasion and corruption forms part of PM Imran Khan’s larger political agenda. Experts claim that laws passed hurriedly in September 2020, claiming to be in compliance of the pending FATF review, also entail a lot of arbitrary and excessive powers that are likely to be used for political persecution of opponents.18

It is noteworthy that the basic issue, which has been continuously flagged by the FATF against Pakistan, relates to terror financing and action against proscribed persons and entities. This is where it has been failing and this is where it has to deliver. Under a risk-based approach, critical failing in even one criterion can lead to black listing. Taking a parallel example, in 2005, Switzerland was flagged for monitoring regarding its opaque rules of beneficial ownership of legal persons and cash couriers.19 Based on such risks, Switzerland was made to comply and it did not matter that it had majorly complied with most other technical recommendations.

Is There an Economic Cost?

Post grey listing, Pakistan’s credit ratings were downgraded.20 This credit rating downgrade has a negative impact on rate of interest which, in turn, has adverse impact on economic growth. But apart from the credit ratings downgrade, which may have been caused by factors other than grey listing, what do other economic parameters say? For analysing this we consider trends in some key macroeconomic parameters when Pakistan was on the grey list.

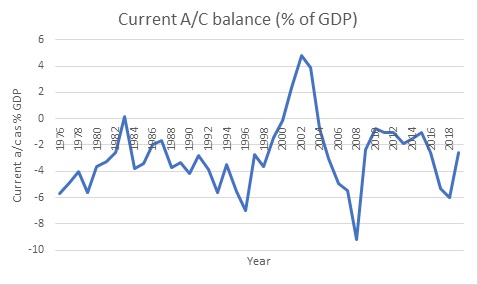

Figure 1 shows that Pakistan has a long-term trend of current account deficit leading to constant pressure on balance of payments. But contrary to expectation, during the period 2012-15, its current account position was only a shade better as compared to its historical average and showed some degree of stability.

Figure 1: Current Account Trend of Pakistan

Source: World Bank21, compiled by author.

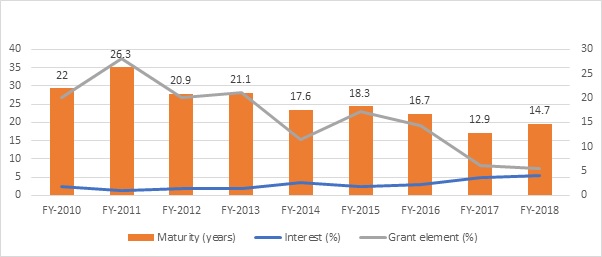

Figure 2 below shows that the debt maturity period had no particular trend from 2012-15 but started decreasing after 2015. It shows that Pakistan’s quality of debt deteriorated and became more short term post 2015, which is counter-intuitive.22 Similarly, the interest rate has been rising after 2015 after moving up and down from 2012-15. The grant component of foreign loans also decreased since 2015. This indicates that Pakistan is relying more on short term high interest loans which are riskier.

Figure 2: Debt Maturity in Year, Average Interest Rate on Debt, and Element of Grant

Source: International Debt Statistics 202023, World Bank, compiled by author.

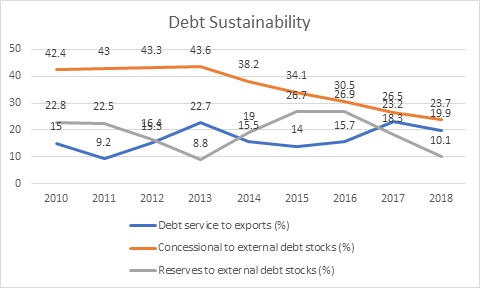

Similarly, as per Figure 3 below, Pakistan’s debt service to exports position and reserves to external debt stock position improved between 2013-15 as it had decreasing debt servicing obligations to exports and increasing forex reserves cover for that debt.24 After 2015, this started deteriorating. The percentage of concessional debt, which is generally preferred as it has low interest rates, has been going down since 2013.25

Figure 3: Quality of Debt Servicing Indicators

Source: International Debt Statistics 202026, compiled by author.

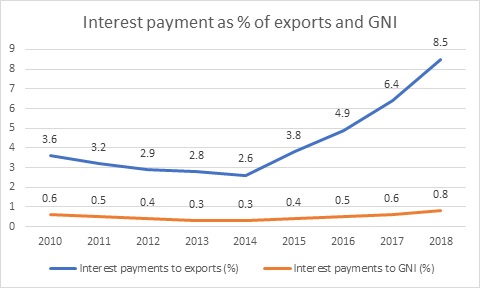

As Figure 4 below shows, Pakistan’s interest payment to exports ratio and interest payment to Gross National Income (GNI) ratio improved till 2014 and has been deteriorating since then. For part of the period when Pakistan was grey listed, its debt sustainability as measured by interest outgo was actually improving; since 2014 this has been going down.27

Figure 4: Sustainability of Interest Payments

Source: International Debt Statistics 2020,28 World Bank, compiled by author.

The above figures show that for the large part of 2012-15, Pakistan’s macroeconomic parameters interest rate, quality of debt and its sustainability, governing its external sector were largely stable or had a secular trend. They also reveal that these parameters had started deteriorating much before June 2018. This shows that grey listing had a minimal impact on economic performance and it is largely ineffective in imposing economic costs on the target jurisdiction. This finding further corroborates the analysis as to why grey listing by the FATF remains largely ineffective in bringing any real change in Pakistan’s behaviour.

A related question which needs answering is: if grey listing is really ineffective, then why is Pakistan making any effort after all at passing laws or making perfunctory changes? And what accounts for the media buzz inside Pakistan regarding grey listing this time?

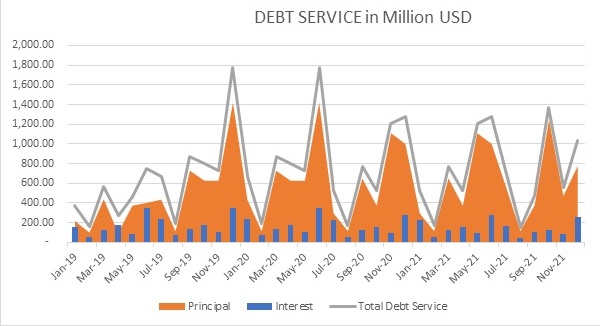

The answer may lie in the fact that the country’s economic parameters have been deteriorating for some time and its economy is currently very vulnerable. On a more ominous note, Figure 5 shows that starting from mid-2019, Pakistan is required to service huge amount of external debt in dollars. These include maturing of old-time debts now as well as short term debts incurred lately. This makes Pakistan’s economy particularly vulnerable over the next few years and any likelihood of progression to black listing will be particularly problematic. This timeline also underlines the fact it is not the grey listing per se but Pakistan’s persisting economic weakness coupled with the threat of possible black listing, which is worrying its government.

Figure 5: Future Debt Servicing Liabilities of Pakistan

Source: World Bank Debtor Reporting System,29 compiled by author.

This is not to say that grey listing may not have any impact on Pakistan’s economy. The idea of “naming and shaming” by FATF may have a cost. As FATF works with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank as well, the IMF has also been putting conditionalities linked to FATF related compliances before giving bail-out packages. However, grey listing doesn’t seem to be the main cause of Pakistan’s economic woes though it may be exacerbating an already present malady.

Another related question is: what are the costs of black listing by the FATF? Some literature indicates the not-so-serious monetary effect of black listing and also calls for even tougher a FATF regime for non-cooperative jurisdictions.30 By and large, however, there is a larger consensus that black listing leads to severe consequences for the target economy. Currently, only Iran and North Korea are placed on the FATF black list, which may indicate its seriousness.

Weakness in the FATF Listing Regime: A Case for Different Shades of Grey

It appears that as far as severity of consequences is concerned, the black list is a quantum jump over the grey list. It is a serious escalation with very high costs. For an already weak economy like Pakistan, it could even lead to large scale turmoil and default. Akin to the nuclear option, this leads to a very high threshold for black listing.

This structural weakness in the FATF is also reflected in the somewhat brittle or simplistic categorisation structure of different jurisdictions into so-called white, grey and black. This straightjacketed view may not permit a flexible and graduated response. The reason is a very substantial jump in international commitment when putting some country on to the black list. Madeleine Albright, former US Secretary of State, once called Pakistan an “international migraine”.31 To put it bluntly, the international community may be trying to avoid turning a migraine into a brain tumour by black listing. But Pakistan is also aware of this dilemma, that the only option available to the FATF after the grey list is one it may not be willing to take. So in place of gaining leverage the FATF is actually losing it through this structure. This high threshold provides considerable space for manipulation and manoeuvre to a country like Pakistan. Another deficiency already considered is the natural difficulty faced by most organisations in dealing with hybrid regimes like Pakistan, the FATF being no exception.

Analysing the problem faced by the FATF and risk associated with all the available options, some scholars have tried to take the middle ground and suggest keeping Pakistan in the grey list only.32 Their basic argument is that Pakistan has definitely not done enough to move from the grey to the white list. Black listing may lead to it being a pariah and this may have severe consequences.

The drawback with this approach is that, first, it does not solve the problem and, second, it undermines the effectiveness of FATF as an institution. As timelines are being missed, news of geopolitical considerations playing an increasing role in FATF meetings keep coming out. News of voting based on geopolitical consideration undermines the consensus-based technical nature of the FATF deliberations. Thus, status quo may not be the solution.

A possible option worth exploring may be to generate policy options for graduated but firm response while moving between the grey and black lists, that is, there may be a scope for darker shades of grey. Though the FATF has adopted a Risk Based Approach, the grey list shows countries as diverse as Mauritius, Pakistan, Syria, Jamaica, Iceland and Barbados being clubbed together. They all may have some strategic deficiencies vis-à-vis the FATF standard, but, qualitatively, do they pose the same degree of risk? For example, the FATF targets weapons of mass destruction (WMD) proliferation, corruption, money laundering and terror finance. There is, however, a difference in risk between political corruption leading to money laundering and nuclear weapon proliferation or financing terror. The present system lumps all such jurisdictions with different qualitative risks in one grey list basket. Differentiating may help the FATF better assess the risk posed by Iceland or Jamaica as opposed to, say, Pakistan.

There may be those jurisdictions in the grey list that have the will to implement the FATF Recommendations but may lack the necessary technical or administrative capacity. At the other extreme, jurisdictions may have the capacity but would be unwilling in intent. A necessary categorisation may be made in the grey list which captures this crucial aspect. The countries which may be willing to act but lack capacity should be given technical support. But countries like Pakistan, which largely lack the will to implement, may be put in the darker shade of grey and sanctioned more severely. This should help in better targeting.

After categorising the severity of the source of risk followed by whether the country has the necessary capacity/will, or not, a graduated response may be designed in consultation with different constituents like credit rating agencies, banks, IMF and WB, etc. This approach may provide more flexibility in tackling jurisdictions which may be undermining the FATF by repeatedly giving assurances but not acting on them in any substantial way.

The time may be right for such a discussion as FATF is already in the process of undertaking a strategic review of its Methodology of assessment by 2021. It is committed to making FATF more effective by strengthening risk-based elements of the assessment process.33

Going by its record of policy innovation and flexibility, it is safe to assume that FATF will again rise up to the challenge.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “Pakistan Parliament Joint Session Passes 3 FATF-related Bills to Avoid being Blacklisted”, The Print, September 16, 2020.

- 2. APG, Anti-money Laundering and Counter-terrorist Financing Measures—Pakistan, Third Round Mutual Evaluation Report, APG, Sydney, 2019.

- 3. See “Improving Global AML/CFT Compliance: On-going Process—24 June 2011”, June 24, 2011.

- 4. See “FATF Public Statement—19 October 2012”, October 19, 2012.

- 5. See “Improving Global AML/CFT Compliance: On-going Process—27 February 2015”, February 27, 2015.

- 6. FATF, International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism & Proliferation, Paris, France, 2012-19.

- 7. See “Hafiz Muhammad Saeed”, United Nations Security Council.

- 8. “Hafiz Saeed Unmoved by Talk of Ban on JuD”, The Dawn, January 25, 2015.

- 9. FATF, Methodology for Assessing Compliance with the FATF Recommendations and the Effectiveness of AML/CFT Systems, 2013-19, updated October 2019, Paris, France.

- 10. Katharine Adeney , “How to Understand Pakistan’s Hybrid Regime: The Importance of a Multidimensional Continuum”, Democratization, 24 (1), pp. 119-137. Also see Foqia Sadiq Khan, “Hybrid Regime”, Daily Times, October 31, 2019.

- 11. Cyril Almeida, “Exclusive: Act against Militants or Face International Isolation”, The Dawn, January 9, 2017.

- 12. “Nawaz Sharif has Spoken. But Can He Change the Pakistan Army’s Game”, The Print, September 23, 2020.

- 13. “Pakistan Reneges on its Promise to End Support to Cross-border Terrorism in India”, India Today, September 13, 2004.

- 14. “Hafiz Saeed: Will Pakistan’s ‘Terror Cleric’ Stay in Jail?”, BBC, February 13, 2020.

- 15. “Read the Full Court Order to Understand Pakistan’s Game in Jailing Hafiz Saeed”, The Print, February 21, 2020.

- 16. “Pathankot Airbase Attack: FIR Registered in Gujranwala against Attackers, Abettors”, The Dawn, February 19, 2016.

- 17. “Read the Full Court Order to Understand Pakistan’s Game in Jailing Hafiz Saeed”, The Print, February 21, 2020.

- 18. Mohammad Taqi, “Pakistan’s Hybrid Regime: The Army’s Project Imran Khan”, The Diplomat, October 1, 2020.

- 19. See FATF, Third Mutual Evaluation Report of Money Laundering and Terrorism—Switzerland, October 14, 2005.

- 20. Vivek Chadha, “FATF as an Instrument of CFT Compliance in Pakistan”, IDSA Issue Brief, 2018.

- 21. See “World Development Indicators—Economy”, The World Bank.

- 22. A financially robust economy would have more long term debt and less short term debt, as the former has less risk associated with it. In the case of Pakistan, the period it spent on the grey list should have seen movement towards more short term debt; however, this is seen once it is removed from that list.

- 23. See “Data Topics”, World Bank.

- 24. Debt service to exports refers to the ratio of money to be paid in foreign exchange as interest on principal for debt service upon forex earned on exports. This is ideally on an upward trajectory when the external part of a country’s economy is doing badly. Reserves to external debt stocks is the foreign exchange cover a country has to service its debts. This should go up when the country’s economy is improving.

- 25. Concessional debt refers to debt which is incurred at low interest rates or their payment terms are long term or easier. If this comes down, as in the case of Pakistan from 2013 onwards, then the indication is that the country is relying on riskier and poor quality debt.

- 26. “International Debt Statistics 2020”, World Bank.

- 27. The above ratios show interest payment liabilities as compared to exports and GNI. If the ratio is going down it means interest liabilities are decreasing and are more sustainable.

- 28. Ibid.

- 29. Ibid.

- 30. W. N. Shahin, E. El-Achkar and Rana Shehab, “The Monetary Impact of Regulating Banking and Financial Sectors by FATF on Non-cooperative Countries and Territories”, Journal of Banking Regulation, 13, pp. 63–72, 2012.

- 31. “Pakistan Continues to be an International Migraine: Albright”, Business Standard, January 24, 2013.

- 32. Abdur Rehman Shah, “India and Pakistan at the Financial Action Task Force: Finding the Middle Ground between Two Competing Perspectives”, Australian Journal of International Affairs, 2020.

- 33. See “Outcomes FATF Virtual Plenary, 24 June 2020”, June 24, 2020.