Chinese intrusions across the LAC

Reacting to President Pranab Mukherjee’s visit to Arunachal Pradesh in November of this year, the Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Qin Gang stated that “We hope that India will proceed along with China, protecting our broad relationship, and will not take any measures that could complicate the problem, and together we can protect peace and security in the border regions”.1 China has routinely protested top Indian policymakers visiting Arunachal Pradesh which it claims as its territory along with Aksai Chin. In October 2009, China expressed deep dissatisfaction when Prime Minister Manmohan Singh visited Arunachal Pradesh as part of an election campaign for the state assembly elections. China again reacted sharply to the visit of the Indian Defence Minister, A K Antony to Arunachal Pradesh when on February 25, 2012, the Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson, Hong Lei stated that such visits create complications towards resolution of the border issues. This issue is further complicated by a 4, 000 km border dispute.

Recently, a Border Defence Cooperation Agreement (BDCA) was signed between China and India during the visit of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to China.2 Both sides agreed to refrain from military offensives at the border and share information on military exercises near the Line of Actual Control (LAC) through regular border personnel meetings. The good news about the BDCA is that it institutionalizes the process of conflict management at the border, if and when intrusions take place.

The bad news is that the agreement does not resolve the differing perceptions of the LAC itself. Hence, intrusions will continue to occur. The other critical issue which remains unresolved is China’s claim over 90, 000 square kms of territory in India’s eastern sector and 38, 000 square kms of territory in the Western sector. History will tell us that territorial disputes between major powers with geographic proximity have resulted in military conflict. Moreover, the likelihood of conflict is high when the political systems embroiled in territorial disputes differ: China’s authoritarian system versus India’s democracy.

The Pattern

What has been the pattern of China’s border intrusions? For one, it has occurred on both sectors. Second, it has increased in the last few years. For instance, Chinese intrusions across the LAC totaled 180 in 2011 and had a rising trend in 2012 going forward. Third, these intrusions are determined to make China’s presence felt at the LAC.

Tense and dangerous situations kept lurking on the LAC in 2012.3 In May 2012, two PLA patrols comprising 50 soldiers reached Thangla, Chantze, in West Kameng District of the eastern sector only turning back after they met with Indian forces. 30 PLA soldiers crossed over to Asaphila in Arunachal Pradesh on May 19 and destroyed a patrol hut of the Indian forces.4 A PLA patrol painted China on the rocks near Charding-Nilung Nala in Demchok in Ladakh on July 8, 2012. Such events continued with further intrusions by China in the Trig Heights and Pangong Tso Lake.

In the spring of 2013, the border witnessed another altercation when a Chinese border patrol set up camp in the Ladakh sector of Jammu and Kashmir. The Chinese intrusion in the remote Daulat Beg Oldi sector may have, as evident from the flag meeting minutes, been in retaliation of the Indian Army’s construction of a single watch tower along the LAC in Chumar division.5 Chumar, a remote village on Ladakh-Himachal Pradesh border, is claimed by the Chinese as its own territory and have been frequented by helicopter incursions almost every year. Chumar represents a Chinese vulnerability as it is the only area across the LAC to which the Chinese do not have direct access. On July 16, 2013, 50 PLA soldiers riding on horses and ponies crossed over into Chumar and staked their claims to the territory and only went back after a banner drill with the Indian border troops. This had been preceded by two Chinese helicopters violating Indian air space over Chumar on July 11. This intrusion coincided with India’s decision to raise a Mountain Strike Corp of 50, 000 along the China-India border.6 On August 13, 2013 Chinese troops intruded more than 20 kilometres inside the Chaglagam area of Arunachal Pradesh and stayed there for two days.

The Vortex

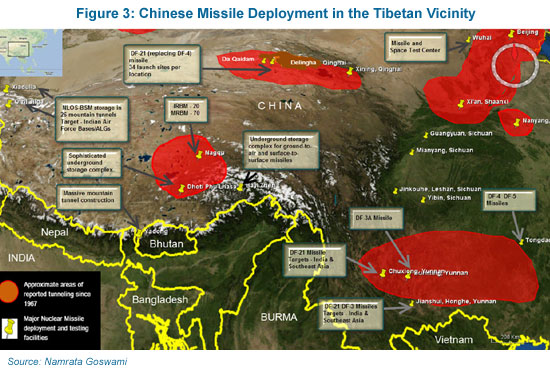

Bolstering such aggression at the border is China’s steady expansion of military capabilities centered in the plateau of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). China has been shooting for border dominance via military means and has built the required military infrastructure throughout the TAR. The operational objectives are to initiate and sustain intense ‘shock and awe’ type blitzkrieg short campaigns against India. The military machine to achieve these objectives consists of land and air forces backed by stockpiled logistics and supplies. China has built road and rail networks in Tibet, which provide ground mobility to 400,000 PLA soldiers in the two military regions opposite India. It has deployed upgraded ballistic missiles, added several new dual use airfields in Tibet and expanded its military assets transport capability. Advanced Chinese fighter aircraft stationed in TAR are capable of operating at high altitudes.

What is however interesting to note is that in the overall scheme of China’s airpower there are no major air bases within short strike range of India. Rather, in the PLA’s battle strategy, the Indian air force assets across the LAC will be ideal targets for the PLA ballistic missiles stockpiled in underground tunnels built into the mountainside in Xinjiang and Tibet. These missiles are located in proximity to the LAC with ready access from the Western Tibet highway.

To destroy the supply logistics and transportation of Indian ground forces up to the LAC, the PLA plans include rocket artillery massed fire-assaults combined with air strikes. To war-game out such a theatre, the PLA conducted its first joint Army-Air Force live-fire exercise on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau simulating the higher altitudes of the Himalayas in 2010.7 Interestingly, the Chinese military transported combat equipment for the exercise using the Qinghai-Tibet railroad, which was a first. The PLA and the PLAAF (PLA Air Force) followed up in 2011 with live-fire exercises on the lower plateau and higher mountains on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. For example, the PLAAF assets deployed in the Shigatse air base such as Su-27SKs, Su-27UBKs and J-10s engaged in air sorties in coordination with ground-based radar.8 Again a closer look at the level of PLAAF component in these exercises were limited to roughly platoon sized detachments reflecting the absence of offensive strike and power projection air capabilities in the TAR. But certainly these exercises threw up a lot of smoke and noise intended for the Indians who had their ears pressed to the ground not far away.

The real component of China’s operational strategy vis-à-vis India at the border are its missiles deployed to the Tibetan vicinity. China replaced its old liquid fueled, nuclear capable CSS-3 intermediate range ballistic missile with “more advanced CSS-5 MRBMs”. Intercontinental missiles such as the DF-31 and DF-31A have been deployed by China at Delingha, north of Tibet. China has also deployed the solid fuelled DF-21 in Delingha with a range of 2, 150 kms, which is within striking distance of Delhi (2, 000 kms from Delingha). The DF-21 can be launched from either a 13 or 15 metres diameter pad difficult to detect by satellites because of its mobility. Missiles can also escape detection since they are housed in underground tunnels. Such tunnels exist in Yatung, in the Chumbi valley, close to Sikkim.9

Motorized Capability

Tibet offers a flat surface which augments motorized mobility, which China has exploited fully. China has deployed Main Battle Tanks (MBT) and infantry combat vehicles in Tibet for defensive purposes in case there is a future conflict with India. As well as the mountainous region opposite Northeast India, MBTs have been hauled up and positioned along the LAC. On August 18, 2013, the Tibet Military Command (TMC) of the PLA conducted a wartime river-crossing support drill organized by an engineer regiment in the waters of the Yarlung Tsangpo River. The regiment conducted the drill with new-type heavy pontoon bridge equipment.10

The PLA’s ace card is however it’s Construction Corps workforce, a highly efficient and disciplined force that can roll out metaled roads during war. Gravel roads on the LAC enable better water drainage during the monsoons as well as avoids Indian radar, which the PLA has taken full advantage of, having the quick capability of converting gravel roads to black topped. The PLA has an edge over the Indian Army at the LAC since it is not tasked to maintain a constant physical vigil, rather content with the usage of networked and remotely-controlled surveillance systems. These surveillance capabilities are augmented with strategically built barren flat ground patches along the LAC to serve as helipads for deploying Rapid Reaction Forces (RRF) whenever required.

The RRF, also called the ‘Resolving Emergency Mobile Combat Forces (REMCF)’ is the PLA’s rapid strike force. The airborne RRF are strategically located within TAR and can be rapidly deployed within 48 hours on the LAC through the network of medium-lift and attack helicopters. The PLA deployment on the LAC opposite Arunachal Pradesh is drawn from the General Army bases in Chengdu and Yunnan. Interestingly, the flanking maneuvers of airborne units combined with jungle warfare training of the PLA units have been strategized to unleash the localized blitzkrieg effect. These efforts are vindicated by dual-use airports near the LAC at Shigatse Pingan and Ngari Gunsa in addition to Lhasa, Nyingchi, and Qamdo airports.11 The surface transportation backbone in the TAR include highways, the railway line and oil pipeline from Gormo to Lhasa, the eastern highway from Chengdu to Lhasa and the western highway running along the LAC though Aksai Chin.

Policy Insights

Three critical policy insights can be drawn from China’s intrusions across the LAC and military development in TAR and neighboring areas.

First, China’s repeated intrusions are bolstered by its rapid military infrastructure development in its own border regions.

Second, China feels compelled to showcase its military presence to India across the LAC due to its own “vulnerability perception” and lack of political legitimacy in Tibet. China is deeply suspicious about the intentions of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan-Government in Exile in India. China interprets India’s support to the Dalai Lama as a long term Indian strategic objective to free Tibet from China. Hence, any increase in Indian military presence near the LAC is viewed, not only as Indian assertiveness on the border but also connected to plausible Indian plans to provide support to a restive Tibetan population in Tibet.

Third, the US “pivot to Asia” policy has only made China more aggressive with regard to its territorial claims as is seen by its unilateral declaration of an “Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ)” over the disputed islands in the East China Sea. The new President Xi Jinping is apparently following an aggressive Chinese posture with regard to its territorial claims. India must therefore remain alert to the fact that escalation across the LAC is likely despite the BDCA. Moreover, India must game out the likely security consequences if China decides to suddenly impose a similar unilateral ADIZ over Arunachal Pradesh.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “China, India Spar Over Disputed Border”, Reuters, November 30, 2013 at http://in.reuters.com/article/2013/11/30/india-china-border-idINL4N0JF06… (Accessed on December 3, 2013).

- 2. “Border Defence Cooperation Agreement between India and China”, Beijing, October 23, 2013 at http://pmindia.gov.in/press-details.php?nodeid=1726 (Accessed on November 26, 2013).

- 3. Ibid.

- 4. Saurabh Shukla, “Growing Intrusions by the Chinese Army on the LAC Has Set Alarm Bells Ringing in South Block. Can the Indian Army Maintain Restrain?” Mail Today, October 16, 2012 at http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/sino-indian-border-dispute-chinese-ar… (Accessed on November 25, 2013).

- 5. PTI “Face-offs Continue; China has Built 5km Road Inside Indian Territory”, The Times of India, May 26, 2013 at http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2013-05-26/india/39537733_1_… (Accessed on November 23, 2013).

- 6. PTI, “50 Chinese Soldiers on Horses Intruded into Indian Territory”, The Hindu, July 21, 2013 at http://www.thehindu.com/news/international/world/50-chinese-soldiers-on-… (Accessed on November 28, 2013).

- 7. “China’s Military Drill in Tibet”, Reuters and CCTV Videos, April 3, 2010 at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-JqraQsXAwo (Accessed on December 5, 2013).

- 8. For more, see Christina Lin, “PLA on Board an Orient Express”, Asia Times Online, March 29, 2011 at http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China/MC29Ad03.html (Accessed on November 27, 2013).

- 9. For more on this aspect, see Hans M. Kristensen, “Extensive Nuclear Missile Deployment Area Discovered in Central China” Federation of American Scientist Strategic Security Blog, May 15, 2008 at http://blogs.fas.org/security/2008/05/extensive-nuclear-deployment-area-… (Accessed on December 3, 2013).

- 10. “New-type Heavy Pontoon Bridge Commissioned”, People’s Daily, August 14, 2013 at http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8363343.html (Accessed on November 27, 2013).

- 11. Claude Arpi, “The Dual Use of Airports in Tibet”, August 6, 2013 at http://claudearpi.blogspot.in/2013/08/the-dual-use-of-airports-in-tibet…. (Accessed on December 5, 2013).