Indian Army in the East African Campaign in World War I

- July-September 2015 |

- Africa Trends

Introduction

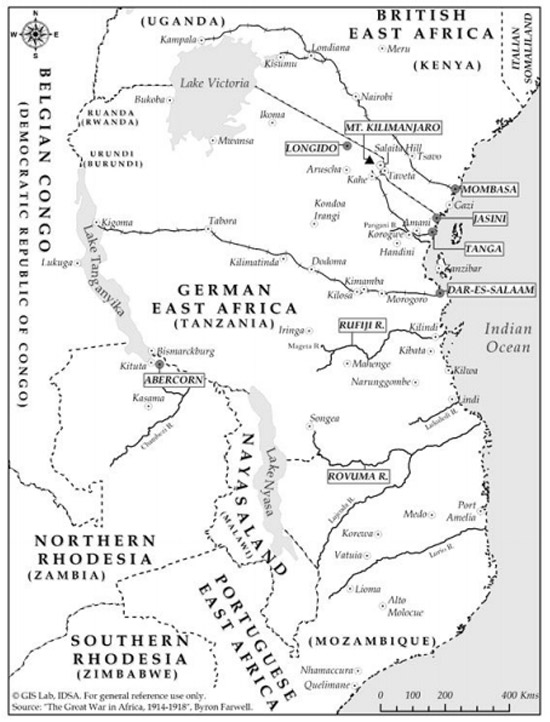

After a lapse of over a hundred years, it is good to recall what happened in the then German East Africa or GEA (now Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi). The British protectorates of Uganda (1894) and British East Africa (1886) in the north and Northern Rhodesia (1893) and Nyasaland (1891) in the south, bordered German East Africa1 . Belgian Congo (now Democratic Republic of Congo) was to the west of German East Africa. Portuguese East Africa (now Mozambique) was to the south of Rouma River.

Objective history is best written after a lapse of time when the participants are no more alive and there is no victor or vanquished. The trend of inter – state war has drastically reduced, and today all participating entities of the yesteryears are free countries. Past enemies are now friends.

Unlike the Official History of the Indian Armed Forces in the Second World War, there is no official history of the Indian Armed Forces in the First World War. Recently commenced archival research reveals interesting details about Indian troops in Africa.2 During the Great War, seven Indian Expeditionary Forces (IEF) from ‘A’ to ‘G’ were employed of which IEF ‘B’ and IEF ‘C’ are of interest. In the four year period from 1914 to 1918 nearly 50,000 Indian troops passed through East Africa. At any one time in-theatre there were about 15,000 troops. A total of 2,972 were killed, 2003 wounded and 43 missing or taken prisoners of war taking the total casualties to 5,018 including all ranks.3

The War

German Protective Force ( Schutztruppe)

At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, German East Africa in its Protective Force ( Schutztruppe) had just over 200 Europeans and less than 2,500 native soldiers called Askaris recruited from the tribes such as Bantu, Wahuma, Masia and Zulu. There was limited artillery and other logistic units and as the war progressed, more Askaris were recruited and the white population also lent a hand in fighting, as also sailors with their naval guns, whose warships had been either sunk or rendered out of action near the coast. The basic fighting unit was an integrated company which was self contained for foot mobility and small boat for river crossings. 40 year old charismatic bachelor with excellent leadership qualities, Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, was the overall military commander. His grand strategy was to help the war effort in Europe by tying down the maximum number of enemy troops in this “African diversion that would attract Allied military resources”.4 He relied on leading from the front, mobility, surprise and seizing the initiative. As he was outnumbered and cut off from supply base from Europe, he resorted to “Fabian Strategy” 5 which avoided direct confrontation, harassing the enemy and cutting him off to exhaust him. In the four years of the war, the commander never surrendered and kept the front mobile by timely withdrawal and evasive action where possible. Three more factors can be attributed to superior performance of the Protective Force (Schutztruppe). First, the Askaris were hardy warrior-like locals who knew the terrain and were immune to the tropical diseases. The second was that they were operating on interior lines, and third, they were living off the land including getting local labour for defence works/porters. Due to blockade, the Germans also improvised local manufacture of ammunition and military stores. Although few German ‘blockade runners’ supply ships managed daringly to reach GEA from Europe, the Germans also resorted to what is the mantra of any guerrilla fighter : “the best quartmaster is the enemy” by capturing supplies, and equipment including that of the Portuguese from Mozambique .

Sequence of Events: IEF ‘B’ and IEF ‘C’

In August 1914 it was decided to send IEF ‘B’ on an expedition to Dar Es Salam (later diverted to Tanga), and IEF ‘C’ to safeguard British East Africa (Kenya) by reinforcing the limited troops of the King’s African Rifles (KAR) . The embarkation ports were Bombay and Karachi.

IEF were made up of three types of troops- units of Indian Army, Indian State Forces and Indian Volunteers (see Appendix). In brief the operation progressed as under :

- September – December 1914. IEF ‘C’ deployed to protect Uganda railways. 29th Punjabis saw first action. Attack on Longido under German control northwest of Kilimanjaro was unsuccessful. With a near 7:1 superiority IEF ‘B’ commenced a botched up landing after losing surprise at Tanga port in November. It was later disembarked at Mombasa to build up on IEF ‘C’ in British East Africa. An attack on Jasin (also spelt as Jasini or Yasini), a coastal village was a success.

- 1915. Colonel Raghbir Singh Pathania, Commanding Officer (CO) 2nd J&K Rifles (State Force) was killed in action in January in the defence of Jasin, which was later recaptured by the Germans. To the south, in January, Mafia Island at mouth of delta of Rufiji River was captured. Using four lake steamers a mixed force of 2,000 men (which included 29th Punjabis and 28th Mountain Battery) captured Bukoba on the west coast of Lake Victoria. Minor offensives were undertaken such as on Mbuyuni near Kilimanjaro in July. Meanwhile German patrols kept on raiding Uganda railway track. South Africa after the conquest of German South West Africa (now Namibia) reinforced British East Africa with the intention of invading GEA with a strong South African Expeditionary Force of white troops (barring one mixed unit). At Salaita, when two South African battalions broke up due to heavy German pressure, firm action by 130th Baluchis saved the day.

- Byron Farwell, The Great War in Africa: 1914-1918, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, London, 1986, p.253.

- 1916. The offensive was first along the railway line and then Germans broke away and did a fighting withdrawal through dense bush. The advancing Indians and South African troops had to suffer miseries due to supplies and lack of administrative support in the tough terrain and climatic conditions. Finally the Germans were slowly pushed till the Rufiji River in the south.6 A series of sea-borne forces as left hooks were employed by Smuts on the ports. “Kilwa was captured by 40th Pathans and the 129th Baluchis and the King’s African Rifles on 16 October 1916 and Kilbata thereafter. The Indian infantry units were supported by Dera Jat Mountain Battery”.7

- 1917-1918. It was wrongly declared by General Smuts (who was transferred to London) that the operations had ended. Under Van Deventer (the South African theatre commander ), weary and exhausted columns of British, Indian and West African troops, with Belgian Congolese additions, advanced towards south east corner of GEA. With a massive expansion of King’s African Rifles (KAR), European and Indian troops were later withdrawn.

South African General Jan Smuts became the theatre commander and from March and GEA was invaded through the Mount Kilimanjaro region; from Nyasaland (now Malawi); from Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia); and across Lake Tanganyika by Askaris from the Belgian Congo (now Democratic Republic of Congo).

Von Lettow-Vorbeck withdrew by crossing Rovuma River into Portuguese East Africa or PEA (now Mozambique). Although Portugal was an ally of the Triple Entente against the Triple Alliance, it was no match to the 2,000 German invaders who captured all their stores and ammunition. The Germans also successfully managed to slip away from a column which had attacked from Nyasaland and PEA ports. The tail end of three Indian units/subunits of artillery, engineers and infantry with logistical units like railways and medical troops remained in East Africa till end of hostilities.8

Just before “an Armistice was being agreed to in Europe Von Lettow-Vorbeck had sprung a surprise on Van Deventer by entering GEA, marching around the north end of Lake Nyasa, and invading Northern Rhodesia”. 9 Two weeks after Armistice was signed, Von Lettow-Vorbeck surrendered with his troops at Abercorn, now Mbala, at the southern end of Lake Tanganyika and thus this campaign came to an end. All sides to this war had one thing in common – great privations suffered by all troops engaged: that is disease, weather and terrain.

Appendix10

Indian Army

Cavalry- one squadron and one unit

Artillery – four mountain batteries

Sappers & Miners – one company, four railway companies, one pontoon park, one engineer field park, one Photo- Litho section and one printing section

Infantry – 17 units

Indian State Forces( Imperial Service Troops)

Artillery – one mountain battery

Sappers & Miners – one field company

Infantry – seven units

Indian Volunteer Force

One battery, one Maxim company , one machine gun company

- 1. S.D. Pradhan, Indian Army in East Africa: 1914-1918, National Book Organisation, New Delhi, 1991, p.22

- 2. Since 2013, the Ministry of External Affairs is supporting ‘India and the Great War Centenary Commemoration Project’ being undertaken by the Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research (CAFHR), United Service Institution of India (USI), New Delhi. This is an international project to reconstruct the history which includes making available archival military records of 13 theatres located in Europe, Africa and Asia.

- 3. Harry Fecitt (authored) , Rana T.S. Chhina (Ed.), Indian Army and the Great War – East Africa 1914-1919, USI of India and XPD Division , Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 2015.

- 4. Ibid, p.5.

- 5. S.D. Pradhan, note 1, p.157

- 6. Harry Fecitt, note 3, p.14.

- 7. Maj Gen Ian Cardozo and Rishi Kumar, India in World War I: An Illustrated Story, Bloomsbury, India, 2014, p.26.

- 8. Harry Fecitt, note 3, p.21.

- 9. Ibid

- 10. Based on Harry Fecitt, note 3.