The Philippines’ Evolving West Philippine Sea Strategy

Introduction

The President of the Philippines Marcos Jr. on 7 November 2024 signed the Philippine Maritime Zones Act (PMZA) (RA 12064) and the Philippine Archipelagic Sea Lanes Act (ASLA) (RA 12065). These laws outline the maritime zones, internal waters, territorial sea, archipelagic waters, contiguous zones, exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and continental shelf.1 These laws have been enacted on account of escalating tensions between the Philippines and China in the West Philippine Sea (WPS) since 2023.

China’s Coast Guard (CCG) has been undertaking coercive actions such as ramming vessels into Filipino ships, harassing Filipino crew members by firing water cannons at them, while a Chinese Navy missile boat has used a military-grade laser at a Philippine aircraft. 2 Over the last two years, multiple skirmishes between Chinese and Philippines forces took place in the WPS including stand-offs at the Second Thomas Shoal and Sabina Shoal and ships swarming Philippine-claimed areas.3

The Philippines government has taken multiple steps in order to address Chinese aggression. It has strengthened its maritime defence by enhancing surveillance monitoring, establishing forward operating bases and international cooperation with partners in the defence field. The two maritime laws signed by President Marcos Jr. provide legality to its claim in the WPS in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Laws of Sea (UNCLOS).4 The Comprehensive Archipelagic Defence Concept (CADC) allows the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) to secure maritime territories and sea lanes of communication.5 These acts and policies stem from the National Security Policy (NSP), which seek to protect sovereign rights over the WPS.

West Philippine Sea and Competing Claims

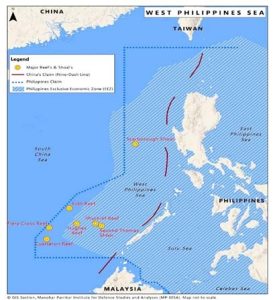

The WPS contains disputed territories in the South China Sea (SCS), including parts of the Spratly Islands, Second Thomas Shoal, Johnson Reef, Mischief Reef and Scarborough Shoal. WPS was adopted after the 2012 dispute between China and the Philippines to emphasise Philippine sovereign rights over this area.6

The WPS is home to a diverse marine life, playing a vital role in supporting local livelihoods and sustaining important fishing industries. According to the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR), WPS has estimated production of 324,312 metric tons of aquatic products.7 This area also has a potential oil reserve of 6,203 million barrels and gas production that may reach up to 12,158 billion cubic feet which would be crucial for the energy security and economic growth of the Philippines.8 Therefore, the loss of the Philippines’ control over the WPS would present significant challenges to the livelihood of the Filipino fishermen.

China asserts claims over the SCS from the Xia dynasty, dating back to the 26th to 16th century BC. They claim that they were first to discover SCS, first to name it, first to map it, first to open sea lanes, first to place local government and accept the Japanese surrender during World War II and retook the sovereign control of the area.9 On this historical basis, they took control over the Fiery Cross Reef in 1988, and the Mischief Reef (which lies in the EEZ of the Philippines) in 1995.10 After the forced occupation of the Mischief Reef through land reclamations, China has put in place military installations that include missile arsenals, aircraft hangers, radar systems and other military facilities that pose a potential threat to the Philippines.11

In response to China’s assertions, the Filipino government introduced the NSP in 2011 during the administration of Aquino III.12 The Duterte administration introduced the NSP 2017–2022 which defined the national interest and a vision of an Independent Foreign Policy (IFP). Later, assuming the presidency in June 2022, Marcos Jr. came with the NSP 2023–2028, indicating a strategic shift in foreign policy and asserting sovereignty over the WPS.

National Security Policy 2017 and West Philippine Sea

NSP 2017 emphasised the integration of development and security, highlighting a comprehensive strategy to address both internal and external challenges. The core idea was centred on ‘security through development’. The NSP 2017 explicitly identified China’s illegitimate actions in the WPS as the primary security challenge to the Philippines’ sovereignty. It stated that “the dispute over the West Philippines Sea remains to be the foremost security challenge to the Philippines’ sovereignty and territorial integrity”.13 Additionally, it outlined a 12-point national security agenda that prioritises military, border security, maritime and airspace security to ensure safety.14 It also emphasised the importance of protecting maritime interests, trade routes and marine resources from piracy, poaching and illegal intrusion through enhanced cooperative maritime security and defence arrangements in the WPS.

It enhanced defence spending for the first time in order to modernise the AFP. Prior to the NSP, the Philippines’ defence spending was the second lowest among the ASEAN constituting only about 1.1 per cent to 1.3 per cent of its GDP.15 With a vision to modernise the AFP, the Philippines bought 12 FA-50,16 PH Fighter Eagle lead-in fighter planes from Korea Aerospace Industries (KAI)17 and 8 AW109 Power Light attack helicopters18.

President Duterte, however, adopted an accommodative stance and appeasement policy with China, often emphasising the importance of bilateral relations and the need for peaceful resolution of disputes.19 He referenced the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling, but was less emphatic about its enforcement and tried to appease China. His IFP lessened Manila’s dependence on Washington while improving relations with China by enhancing economic cooperation and lowering tensions over maritime disputes. Under this policy, improving ties with non-traditional partners like Russia, Japan and India were pursued.20

National Security Policy 2023 and the West Philippine Sea

The NSP 2023 emphasises safeguarding national sovereignty and protecting territorial integrity through a comprehensive approach that includes defence initiatives, diplomatic efforts and developmental strategies. Within the framework of the NSP 2023, there is a concerted effort to bolster military partnerships with various nations. This includes engaging in joint military exercises, facilitating technology transfers, enhancing interoperability among forces, exchanging critical information and coordinating joint maritime patrols to enhance regional security and cooperation. The NSP 2023 also emphasised the ‘revitalization of the Self Reliance Defense Posture (SRDP) Program’, and defence modernisation.21

In a strategic shift to assert its claim over the WPS, the NSP 2023 has empowered the Department of National Defence (DND) and the AFP to safeguard not only the baseline but also the EEZ areas in the WPS.22 The NSP 2023 gives special emphasis towards safeguarding the Philippines maritime zones, in particular WPS, through the National Task Force (NTF) for WPS (NTF-WPS).23

The Philippines has been establishing defence and security cooperation with Indo-Pacific nations deepening its alliance with its traditional partners and cultivating strong ties with the US, Japan, Australia, New Zealand and other like-minded nations while advocating for a rules-based order.24 Furthermore, the Philippines is intensifying military cooperation with various countries to enhance interoperability, facilitate technology transfer, improve capacity building and conduct joint maritime patrols. The US in July 2024 has pledged to provide US$ 500 million of military aid to the Philippines.25 The Philippines Navy has also bought a shore based anti-ship BrahMos missile system from India.26

Conclusion

ASLA and PMZA will have a significant role in the Philippines asserting its sovereignty in the WPS. The PMZA would provide legality aligned with the UNCLOS, and help protect its maritime rights in the WPS.27 On the other hand, the ASLA complements the PMZA in ensuring the protection of the country’s sovereignty and maritime domain, as it defines which sea lanes and air routes can be legally taken in the country’s waters.28 Militarily, the NSP 2017 and 2023 emphasise enhancing military capabilities, modernisation of AFP, defence equipment procurement, maritime domain awareness and coordinated efforts among all national governments. Diplomatically, the Philippines is engaging with China through bilateral communication mechanisms to de-escalate tensions. The country is seeking regional cooperation and support from international partners to counterbalance China’s growing influence in the region. In the third State of Nations Address (SONA) Marcos Jr. asserted that the “West Philippine Sea is not merely a figment of our imagination. It is and will remain ours, as long as the spirit of our beloved country, the Philippines, continues to burn”. The Philippines is following an integrated approach as contained in the PMZA, ASLA and NSPs to ensure its territorial integrity and promote regional stability and cooperation, as it seeks to navigate a complex geopolitical landscape.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “Republic Act No. 12064”, Official Gazette, Government of the Philippines, 7 November 2024.

- 2. Christopher Bodeen, “Chinese and Philippines Vessels Collide at a Disputed Atoll and the Governments Trade Accusations”, Associated Press, 31 August 2024.

- 3. Nestor Corrales, “207 Chinese Ships Swarm WPS; Highest So Far This Year- AFP”, Inquirer.net, 11 September 2024.

- 4. [iv] “New Maritime and Sea Lanes Laws Secure Philippines’ Waters and Safeguard Marine Resources- Legarda”, Senate of the Philippines, 11 November 2024.

- 5. “The DND and AFP have Embarked on the Implementation of the Comprehensive Archipelagic Defense Concept (CADC)”, GIB Teodoro, 8 March 2024.

- 6. Mario Alvaro Limos, “A Brief Explainer on the West Philippines Sea”, Esquire, 17 November 2019.

- 7. Jodesz Gavilan, “Why the West Philippines Sea is Important”, Rappler, 10 November 2021.

- 8. “Gatcgalian Seeks Senate Probe to Unlock Oil, Gas Potential in West Philippine Sea to Cut Import Dependence”, Senate of the Philippines, 16 October 2022.

- 9. Xavier Furtado, “International Law and the Dispute over the Spratly Islands: Whither UNCLOS?”, Contemporary Southeast Asia, Vol. 21, No. 3, December 1999.

- 10. Francois-Xavier Bonnet, “The Spratly: A Geopolitics of Secret Maritime Sea-Lines”, Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, 16 September 2016.

- 11. Derek Grossman, “Military Build-Up in the South China Sea”, RAND Corporation, 22 January 2020.

- 12. “National Security Policy 2011-2016”, Government of the Philippines, 2011.

- 13. Ibid.

- 14. Ibid.

- 15. “National Security Policy 2017-2022”, Government of the Philippines, 2017.

- 16. Renato De Castro, “Developing a Credible Defense Posture for the Philippines: From the Aquino to the Duterte Administrations”, The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, 2014.

- 17. Renato Cruz De Castro, “Caught Between Appeasement and Limited Hard Balancing: The Philippines’ Changing Relations with the Eagle and the Dragon”, Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 25 February 2022.

- 18. “AW109 Power Light Multi-Purpose Helicopters”, Homeland Security, November 2024.

- 19. Anna Malindog-Ug, “Duterte Legacy: China Relations and Foreign Policy”, The Asian Post, 26 November 2024.

- 20. Mico A. Galang, “Understanding President Duterte’s Independent Foreign Policy”, Asia Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation, 17 April 2017.

- 21. “National Security Policy 2023-2028”, Government of the Philippines, 2023.

- 22. Ibid.

- 23. Ibid.

- 24. “ Renato Cruz De Castro, “Philippines and Australia: From a Comprehensive to a Strategic Security Partnership”, Philstar, 27 May 2023.

- 25. Edward Wong, “US Pledges $500 Million in New Military Aid to the Philippines, as China Asserts Sea Claims”, The New York Times, 30 July 2024.

- 26. “Philippines to Buy BrahMos Missile System from India from $375 Million”, The Indian Express, 28 January 2022.

- 27. Sebastian Strangio, “Philippines’ Marcos Signs Laws Aimed at Strengthening Maritime Claims”, The Diplomat, 11 November 2024.

- 28. “Republic Act No. 12065”, Official Gazette, Government of the Philippines, 7 November 2024.